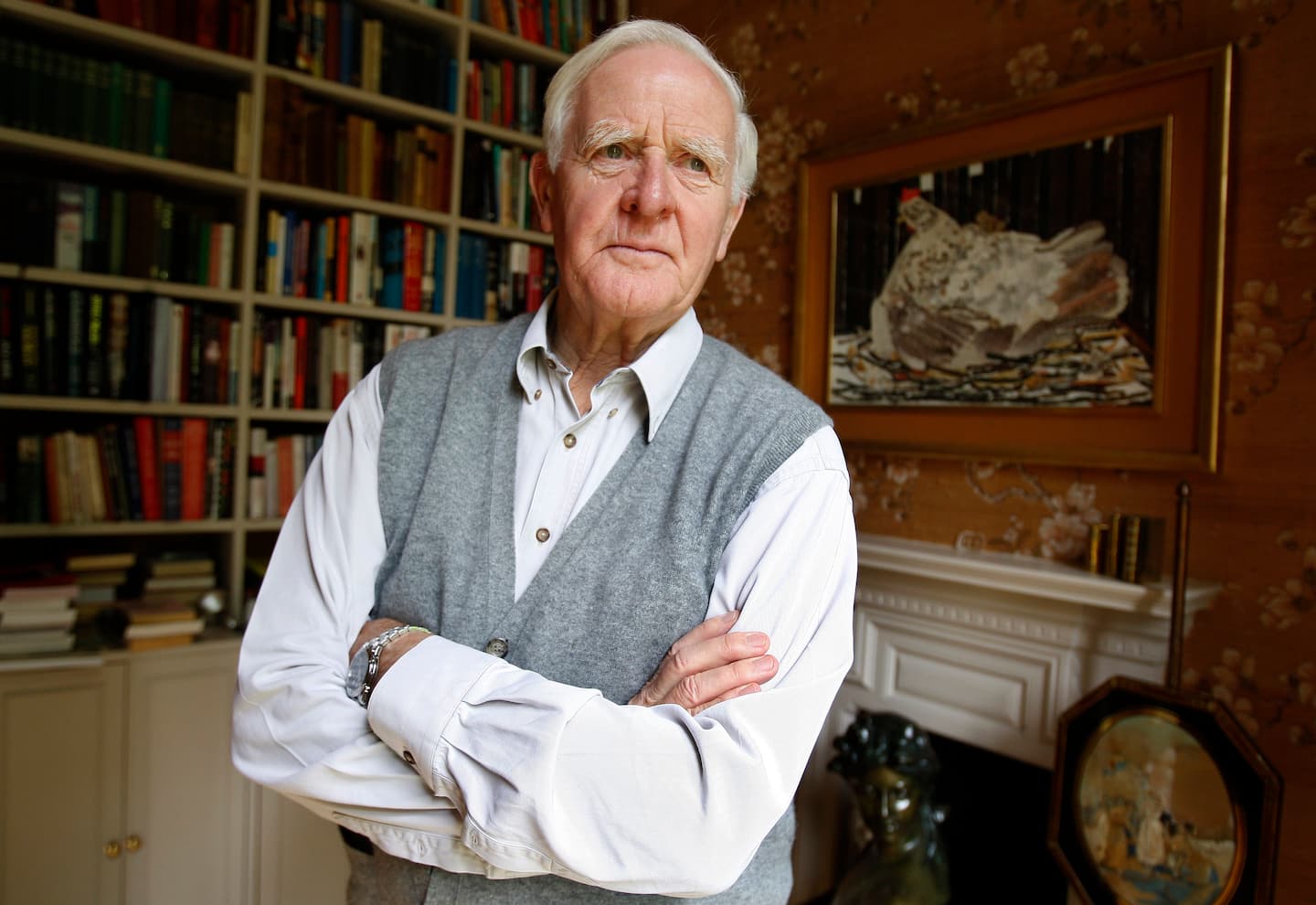

John le Carre, spy novelist, dies

[ad_1]

The cause was pneumonia, his U.S. publisher, Viking Penguin, said in a statement.

In a literary career spanning six decades, Mr. le Carré published more than two dozen books. His best-known titles, including “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold” (1963) and “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” (1974), sold in the millions and were made into acclaimed film and television adaptations. More than a master of espionage writing, he was widely regarded as an elegant prose stylist whose skills and reputation were not limited by genre or era.

After the collapse of Communism in Europe in the early 1990s, Mr. le Carré turned his attention to a changing landscape of global insecurity, sending his fictional spies to Israel, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Central America in such books as “The Little Drummer Girl,” “The Night Manager (1993),” “The Tailor of Panama” and “The Constant Gardener.”

His literary admirers included Graham Greene, Philip Roth and Ian McEwan, who once called him “the most significant novelist of the second half of the 20th century in Britain” and championed him for the prestigious Booker Prize. (Mr. le Carré rejected any entreaties to compete for literary honors.)

“He will have charted our decline and recorded the nature of our bureaucracies like no one else has,” McEwan told the Daily Telegraph in 2013. “But that’s just been his route into some profound anxiety in the national narrative. Most writers I know think le Carré is no longer a spy writer.. . . He’s in the first rank.”

Praised for his cunning plots, psychological complexity and flawed, many-faceted characters, Mr. le Carré also showed a deft hand for misdirection. Even his name was an act of deception: “John le Carré” was a pseudonym adopted by David Cornwell — his given name — because British intelligence officers were forbidden to publish under their own identities.

Having created such brooding anti-heroes as Alec Leamas, George Smiley and Magnus Pym, Mr. le Carré offered an understated view of the spy world that was in sharp contrast to the sex, gadgets and chase-scene formula of Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

Instead, Mr. le Carré’s agents tend to furrow their brows, adjust their eyeglasses and walk inconspicuously along rain-soaked streets, relying on careful observation and endless paperwork. Conversations are muted, offices are shabby and guns remain (mostly) holstered. Everything in his novels, from the weather to the clothing to the fine-grained moral choices, seems outfitted in shades of gray.

Tension builds through cryptic gestures, dry humor or meditative glimpses through windows. Loyalties are questioned, relationships are sacrificed, and the fate of nations seems to hinge on all-too-human frailties.

“Le Carré’s contribution to the fiction of espionage has its roots in the truth of how a spy system works,” novelist Anthony Burgess wrote in the New York Times Book Review in 1977. “The people who run [British] Intelligence totally lack glamour, their service is short of money, they are up against the crassness of politicians. Their men in the field are frightened, make blunders, grow sick of a trade in which the opposed sides too often seem to interpenetrate and wear the same face.”

During his years in Britain’s domestic and international spy services, known as MI5 and MI6, respectively, Mr. le Carré did not hold a high rank. Yet his foreign assignments and his experience in the London headquarters of the spy service — known as “the Circus” in his books — gave his fiction an air of verisimilitude.

He traveled the world for research, cultivating sources as if still engaged in acquiring secrets. In Cambodia, he said he once had to take cover under a car when shooting broke out. When a journalist questioned his memory of certain events they witnessed together, Mr. le Carré replied, “Your job is to get things right. Mine is to turn them into good stories.”

The kind of person drawn to espionage, Mr. le Carré understood, was someone familiar with deception and subterfuge, yet nonetheless driven by a latent sense of patriotic duty. Perhaps the most memorable of Mr. le Carré’s fictional spies was Smiley, “short, fat and of a quiet disposition,” who had a deep knowledge of German literature and an unresolved ambivalence about his occupation.

Introduced as a minor character in Mr. le Carré’s first novel, “Call for the Dead” (1960), Smiley was the central figure in a trilogy that began in 1974 with “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” and continued with “The Honourable Schoolboy” (1977) and “Smiley’s People” (1979). Not exactly a hero, Smiley acts as the moral center in the books, exhibiting a reserved strength and virtue, a quiet embodiment of the British sense of honor.

“At a certain moment, after all, every man chooses: will he go forward, will he go back?” Mr. le Carré wrote about Smiley in “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” “There was nothing dishonourable in not being blown about by every little modern wind. Better to have worth, to entrench, to be an oak of one’s own generation.”

In “Tinker Tailor,” Smiley seeks to find a “mole” — a double agent answering to Moscow — in the British intelligence service. Mr. le Carré based the plot on the real-life double agent Kim Philby, who fled to the Soviet Union after being unmasked.

“It’s the oldest question in the world, George,” a government official tells Smiley, luring him out of retirement. “Who can spy on the spies?”

The story is taut and filled with treachery, but the book is also a revealing study of the various suspects — and of Smiley himself, who learns during his investigation that his wife has had an affair with the mole.

Back in the clandestine chase, Smiley returns to his well-practiced habits of suspicion:

“What of the shadow he never saw, only felt, till his back seemed to tingle with the intensity of his watcher’s gaze; he saw nothing, heard nothing, only felt. He was too old not to heed the warning. The creak of a stair that had not creaked before; the rustle of a shutter when no wind was blowing; the car with a different number plate but the same scratch on the offside wing; the face on the Metro that you know you have seen somewhere before: for years at a time these were signs he had lived by; any one of them was reason enough to move, change towns, identities. For in that profession there is no such thing as coincidence.”

‘Millionaire paupers’

David John Moore Cornwell was born Oct. 19, 1931, in Poole, England. His childhood was one of constant upheaval, in large part because of “the extraordinary, the insatiable criminality of my father and the people he had around him,” he told the Guardian newspaper in 2019.

His father, Ronnie, was an inveterate con man, gambler and rogue. He never held a conventional job, was continually in and out of jail throughout his son’s childhood and got by on his immense charm.

To complicate his early life, Mr. le Carré was 5 when his mother left the family. He didn’t see her again until he was 21. She later said she deserted Mr. le Carré and his older brother because she feared retribution from Ronnie Cornwell and his underworld friends.

Mr. le Carré and his brother, Anthony Cornwell — who later became an advertising executive in New York — attended separate boarding schools and were often left to fend for themselves. Living like “millionaire paupers,” Mr. le Carré wrote that their father would take them to Switzerland for vacations, then sneak out of hotels without paying. At home, the utilities were often turned off because of unpaid bills.

In school, Mr. le Carré endured ridicule and the cruel nickname of “Maggot” but gradually reinvented himself as a proper British gentleman. He saw himself, he told the Guardian, “as a kind of spy, as somebody who had to put on the uniform, affect a voice and attitudes and give myself a background I didn’t have.”

Fed up with his school in England, he left at 16 and enroll at the University of Bern in Switzerland, where he studied German language and literature. He was soon “recruited as a teenaged errand boy of British Intelligence,” he wrote in his 2016 memoir, “The Pigeon Tunnel.”

He was 18 when entered the British military, assigned to an intelligence unit in Allied-occupied Vienna. He interviewed World War II refugees and had his first taste of the world of espionage, helping coordinate agents behind Communist lines.

Returning to England, Mr. le Carré studied at the University of Oxford, where he infiltrated Communist student groups for Britain’s domestic intelligence agency, MI5. After graduating in 1956, he taught German at Eton, an elite English boarding school for boys, then two years later joined MI6. After his childhood, the world of spying presented an odd sense of stability.

“I was unanchored, looking for an institution to look after me,” he told the CBS News program “60 Minutes” in 2018. “I understood larceny. I understood the natural criminality in people because it was . . . all around me.”

Mr. le Carré refused to discuss what he did during his years under cover, except that he posed as a diplomat, usually in German-speaking countries. He published his first three books while still working for crown and country.

He gave various explanations for how he chose his nom de plume — le Carré means “the square” in French — before ultimately admitting he didn’t really know. The success of “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold,” his third book, allowed him to resign from the intelligence service.

Ronnie Cornwell, meanwhile, married several times, had countless affairs and was incarcerated in at least half a dozen countries. Even so, jilted lovers, onetime jailers and men who took the fall for him and served time in prison for his crimes remained in thrall to his charismatic personality.

Mr. le Carré once bailed his father out of jail in Jakarta and, years later, learned that he was entangled in arms dealing and currency fraud, among other shady ventures. When Ronnie Cornwell died in 1975, Mr. le Carré paid for the funeral — but did not attend.

“I think that my great villains have always had something of my father in them,” Mr. le Carré told People magazine in 1993. He drew on strained father-son relationships for several novels, including “A Perfect Spy” (1986) and “Single & Single” (1999).

In “A Perfect Spy,” which critics rank among Mr. le Carré’s finest work, the morally conflicted central character, Magnus Pym, composes a novel-within-a-novel, examining his relationship with his reprobate father and questioning his career as a spy.

Mr. le Carré wrote his books primarily at his home on a remote point in Cornwall, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. In later years, he became outspoken in his opposition to the U.S. intervention in Iraq in the early 2000s and to Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union, known as Brexit. He turned down a British knighthood and other honors but in 2020 accepted Sweden’s Olof Palme Prize for his advocacy on issues of social justice.

A 2015 biography by Adam Sisman suggested that Mr. le Carré’s first marriage, to Ann Sharp, ended in divorce in part because of his emotional coldness and extramarital affairs and her disdain for his literary ambitions. Survivors include his wife since 1972, Jane Eustace; three sons from his first marriage; a son from his second marriage; and several grandchildren.

No fewer than 15 films and television mini-series have been based on Mr. le Carré’s books, including “The Little Drummer Girl” (1984), starring Diane Keaton as an American actress recruited by Israeli intelligence; “The Russia House” (1990), with Sean Connery as a publisher unwittingly caught up in an international arms race; “The Tailor of Panama” (2001), starring Geoffrey Rush as an expatriate British tailor who becomes trapped in a web of lies; and “The Constant Gardener” (2005), with Ralph Fiennes as a diplomat in Africa fighting corruption in the pharmaceutical industry.

Mr. le Carré brought Smiley out of retirement once more in 2017 in “A Legacy of Spies.” In that novel, a protege recalled the smooth, almost seductive way Smiley recruited him:

“ ‘We were wondering, you see,’ he said in a faraway voice, ‘whether you’d ever consider signing up for us on a more regular basis? People who have worked on the outside for us don’t always fit well on the inside. But in your case, we think you might. We don’t pay a lot, and careers tend to be interrupted. But we do feel it’s an important job, as long as one cares about the end, and not too much about the means.’ ”

[ad_2]

Source link