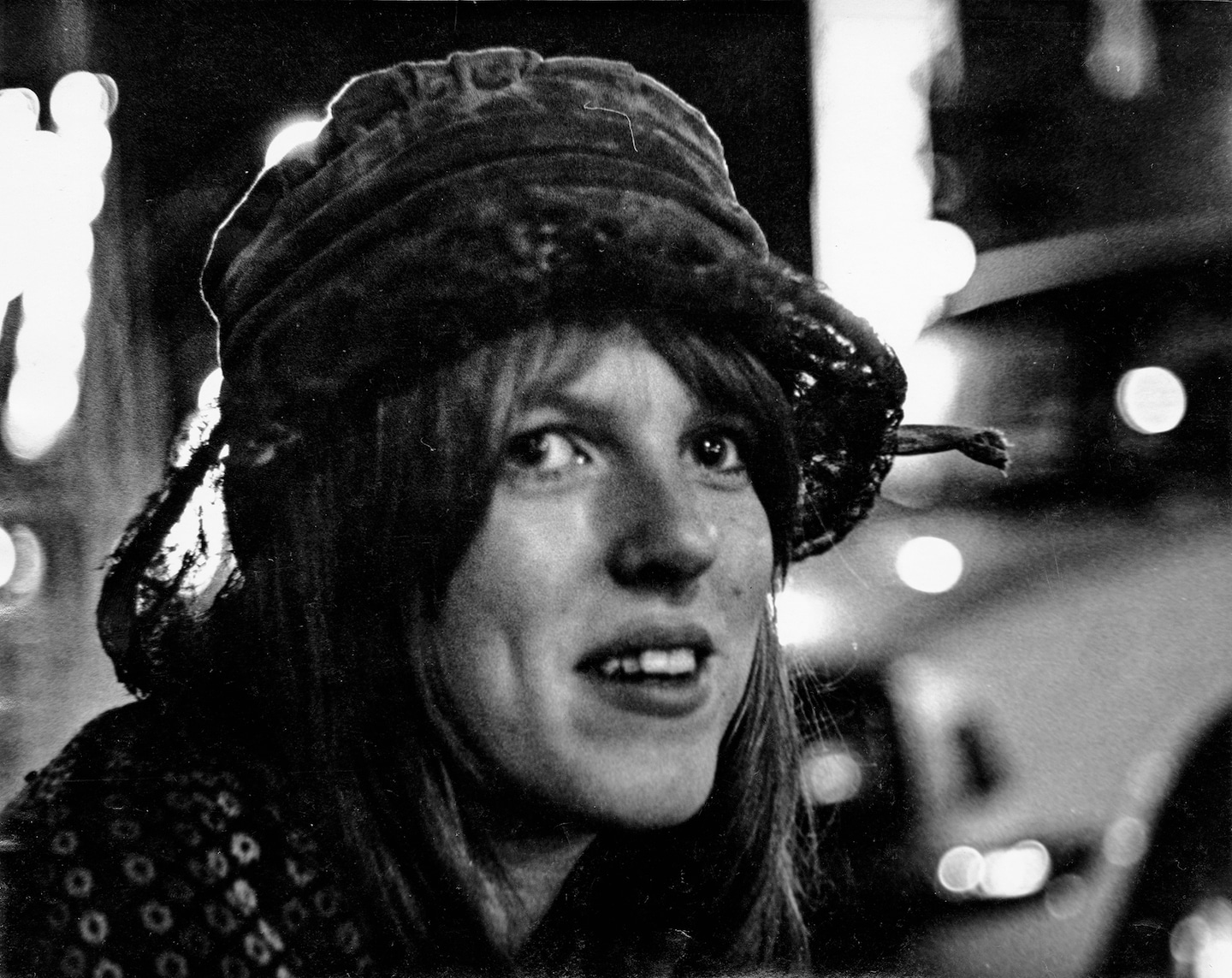

Book review: Lucinda Williams memoir “Don’t Tell Anybody The Secrets I Told You”

[ad_1]

Williams, who turned 70 in January, had an itinerant childhood. Born in Lake Charles, La., the grandchild of Methodist preachers on both sides, she lived in 12 different towns by the time she was 18. Her father, Miller Williams, was a struggling college professor who would become a renowned poet. Lucinda idolized him and for years after she became famous, would continue to submit her song lyrics for his approval. “Honey, this is the closest you’ve come to pure poetry yet,” he tells her upon reading the lyrics to her spartan 2001 album, “Essence.” “You’ve graduated.”

Her mother was a more fraught, unpredictable figure. A talented musician, Lucille Fern Day battled alcoholism, mental illness and the damage done by childhood sexual abuse, allegedly at the hands of her older brothers and Williams’s minister grandfather. “To think that I sat in his lap when I was a kid makes my stomach turn,” Williams writes. By page five, she has already compared her mother to Sylvia Plath, never a good sign. “I learned at a very early age that I wouldn’t be getting from my mother what most kids get from their mothers, the stability and warmth and reliability and support … she was almost like a ghost of a mother — there, but not really there.” Domestic life took a strange turn when Williams’s father invited one of his undergraduate students to live in the house, a young woman he eventually married. Lucinda knew better than to ask too many questions. “My family wasn’t allowed to talk about problems out loud,” she writes. “Everything was held inside.”

Songwriting was a way for Williams to process her traumatic early years, to talk about it without really talking about it, even if she didn’t always realize it. On the title track to “Car Wheels on a Gravel Road,” she describes a crying young child observing their chaotic childhood from a car window. (“Child in the back seat ‘bout four or five years/Lookin’ out the window/Little bit of dirt mixed with tears.”) Williams didn’t understand she was writing about herself until her father pointed it out. “I was amazed and moved at the same time,” she writes. “I had not realized that I was writing about myself the entire time! It took a poet to show me.”

As Miller Williams begins to find success as a poet (he would later read one of his works at the second Clinton inaugural), famous characters, mostly literary, wander in and out of the singer’s childhood: Shortly before her birth, he meets and has a life-changing conversation with Hank Williams. Later, she and her father visit the house of his literary mentor, Flannery O’Connor (Lucinda has to wait outside). During a brief stint in Chile, her father befriends poet Pablo Neruda. Charles Bukowski attended one of her family’s famously raucous house parties and winds up having a drunken hookup in a bed that would later be occupied by a pre-Presidential Jimmy Carter (“He was in town for one reason or another and ended up at my dad’s house,” Williams explains vaguely).

Williams takes up the guitar at 12, and later is kicked out of high school twice for participating in social justice protests before giving up attending traditional school entirely. “You’re not learning anything there anyway,” her father tells her, and begins home schooling her. Within a few years, she lands her first paying gigs.

It’s here that the book’s narrative tone shifts from an unsparing, matter-of-fact southern gothic to a more conventional but equally compelling musical memoir. There are years of low-paying gigs, and countless confidence-sapping day jobs. Long after most of her peers have either made it big or given up, Williams can be found working at a juice bar or a bookstore or passing out samples of tiny sausages on toothpicks at the supermarket. She doesn’t release her first commercial record until she’s 35, doesn’t get famous until the release of her landmark “Car Wheels on a Gravel Road” in 1998, when she is 45. “I’m a complete anomaly in the music world” she writes, “a late bloomer.”

Success brings a different kind of trouble. There are conflicts with (mostly male) record label executives, who tell her she sounds too country to make rock music, and too rock to make country music. There is the churn of constant touring, the ever-present feelings of dislocation and inadequacy and exhaustion.

By the standards of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Williams is the uncompromising leader of an otherwise male band, living like a man in a man’s world. She is hard-drinking and solitary, unyielding and defiant. “I think I was born with a certain kind of resilience, or you could call it rebellious attitude,” she writes. “ ‘Nobody’s ever going to control me’ was my mantra.”

“Don’t Tell Anybody The Secrets I Told You,” written with Sam Stephenson, also chronicles Williams’s romantic life, interspersing her recollections of husbands (two), scoundrels (many), boyfriends and would-be boyfriends with lyrics from the songs they inspired. Williams favors “the roughneck intellectual, the poet on a motorcycle,” damaged Jekyll-and-Hyde types who are kind to her, until they aren’t. One of them attempted to sexually assault her. Another allegedly stole one of her three Grammys. Another told her, “I love you but this relationship doesn’t fit into my agenda right now.”

After Williams become famous, she writes, “a huge range of people were interested in me, including relatively stable people.” She preferred difficult, often emotionally unavailable men, like Replacements frontman Paul Westerberg, and singer Ryan Adams.

In late 2020, Williams suffered a stroke that left her unsteady on her feet and unable to play guitar. She still tours and has a comeback album, “Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart,” which features an assist from Bruce Springsteen, coming out next month. Her book ends years earlier, on a happier note, with her 2009 wedding to label executive Tom Overby. They married onstage at Minneapolis club First Avenue, and honeymooned on her tour bus, “a place where we still today feel quite at home together.”

Allison Stewart writes about pop culture, music and politics for The Washington Post and the Chicago Tribune. She is working on a book about the history of the space program.

Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You

A note to our readers

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program,

an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking

to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

[ad_2]

Source link