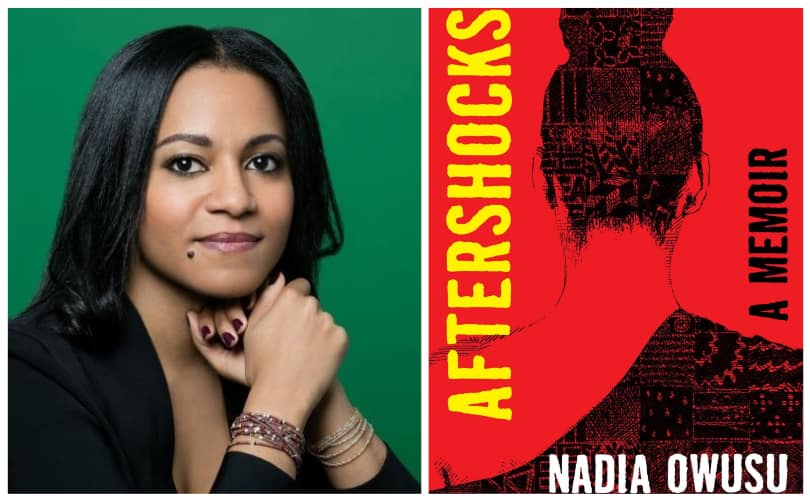

Aftershocks: A Memoir by Nadia Owusu book review

[ad_1]

Given all this, Owusu knows well the complex issues surrounding race and identity. She’s lived them to an unusual degree. In her much-anticipated debut memoir, the 39-year-old Whiting Award winner and urban planner explores the personal price of what could be described as cultural homelessness, while also coping with profound personal losses.

When she was 4, Owusu’s mother abandoned the family; she was 13 when her beloved father died of cancer. This left her and her sister to be raised with their half brother by their East African stepmother. In some ways, the splintering of Owusu’s family parallels the dislocations poet Natasha Tretheway, who is also biracial, documents in her recent memoir, “Memorial Drive” (but without the murder). Both took away a similar lesson. As Owusu puts it, “Grieving, I learned, was a process of story construction. I needed to construct a story so I could reconstruct my world.”

In “Aftershocks,” Owusu’s reconstruction is fractured by design, with a guiding metaphor of seismic shifts; its sections are titled “First Earthquake,” “Foreshocks,” “Faults,” “Aftershocks” and so on; definitions of seismological terms appear between them. Earthquakes have a particularly personal meaning for Owusu: When she was 7, her long-lost mother showed up in Rome to visit her daughters on the same morning that she heard a radio report of a catastrophic earthquake in Armenia. “In me, private and seismic tremors cannot be separated,” Owusu writes.

Owusu’s history gives her the authority to write about many identities with confidence. She sketches in the national character of Tanzanians, her stepmother’s people: they love country music and believe in God. She examines the complex history of Ghanaians, how their complicity in slavery both in the Americas and in their own country resonates through their history. In a particularly engaging part of the book, when she is at boarding school outside London, she regretfully details how she relied on her light skin and her facility with accents to ally her with the most popular English girls and separate herself from Agatha, the only other African.

“Because I was believed to be American, I was expected to behave like the teenagers in the American television shows the girls watched a great deal of when they went home to their parents: My So-Called Life; Beverly Hills 90210,” she writes. And while she had her Aunt Harriet take her regularly to the hairdresser, she watched coldly as Agatha’s extensions grew out and her braids were found in the shower and the breadbasket. She ties her experience to that of Pecola in “The Bluest Eye,” one of several instances when she refers to the work of “the women I had long imagined as a council of mothers: Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Cade Bambara.”

Moving to New York at 18 was not an easy transition. She had her first panic attack on a bus a couple of months after she arrived; she was in the World Trade Center subway station on 9/11; she followed with horror the treatment of Blacks in New Orleans after Katrina. Her accommodation as an African to the lineaments of African American culture recalls moments in both Wayetu Moore’s recent memoir, “The Dragons, the Giant, the Women” and in Chimamanda Adichie’s novel, “Americanah.” In 2010, Owusu’s half brother, Kwame, was picked up by the NYPD. He was released unharmed, but in “the version of the story my mind wrote,” she imagines her brother was shot and killed. She recounts the story of the shooting of her brother in great, although completely fictional, detail, which is a bit confusing tucked into a generally factual memoir. Owusu explains that, “[e]very black mother, sister, and wife in America has written some version of that story in her mind.” Many have also lived it.

A few months after that incident, a breakup with a long-term boyfriend kicked off a period of suicidal ideation and despair covered in four sections that appear over the length of the book. Each is titled “The Blue Chair” after an upholstered rocker Owusu found in the street, dragged home, and sat in for eight days, occasionally forcing herself to eat. “Madness was coming, and no amount of working twice as hard could stop it now. My seismometer sputtered. It was spent, kaput. I had finally heeded the alarm. Now I was on my own. I would have to find my own way out. I hoped, despite my blackness, despite madness, despite the rules of race in America, I would make it out alive.” This memoir represents that bid for survival.

Owusu makes this period of reckoning and high emotional drama the axis around which the rest of the book revolves. Dedicated to “mad black women everywhere,” bursting with flashbacks, flash-forwards, research-based asides, and returns to the Blue Chair, “Aftershocks” is all over the place. Which is exactly the identity it claims. Full of narrative risk and untrammeled lyricism, it fulfills the grieving author’s directive to herself: to construct a story that reconstructs her world.

Marion Winik, a professor at the University of Baltimore, is the author of numerous books, including “First Comes Love,” “The Big Book of the Dead” and, most recently, “Above Us Only Sky.”

Aftershocks

Simon and Schuster. 320 pp. $26