Auction Prices That Take Your Breath Away

[ad_1]

Sale prices that wildly exceed expectations give a jolt of excitement to art auctions. In the prepandemic days of live audiences, a gasp from the crowd might be heard. Though much of the action has moved online, those moments can still send ripples through the art world.

In the last few years, a wave of energy has emanated from a group of 40-and-under contemporary artists whose work has rocketed to enormous prices soon after their first appearance in sales at the big auction houses — in some cases before they have had solo museum shows or passed other milestones on the way to a career in full flower.

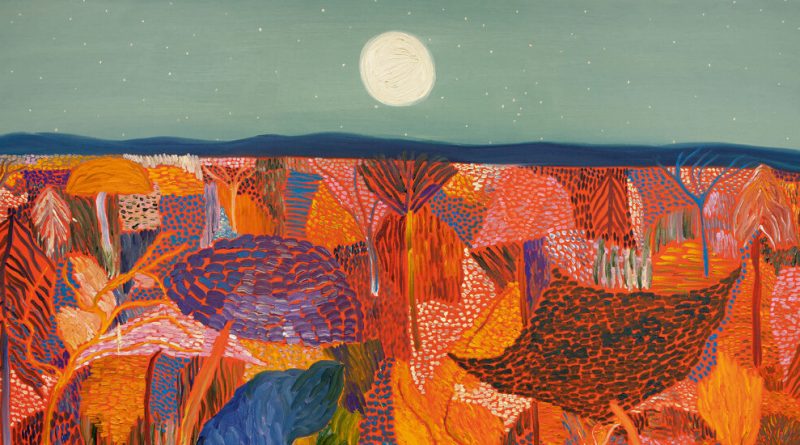

In June 2018, the Swiss artist Nicolas Party, now 40, was a figurative painter on the rise, known for Surrealism-inflected landscapes and still lifes, when he made his first appearance at auction. His 2012 pencil-on-paper “Still Life No 97” made a respectable $11,128 at Christie’s London.

A year and a half — and a couple of decimal places — later, in November 2019, his 2016 pastel “Rocks” made $1.1 million at Christie’s Hong Kong.

A mere six weeks later, his 2018 oil “The Realm of Appearances” sold for a staggering $1.8 million at Sotheby’s New York.

The French artist Julie Curtiss had a sharply upward trajectory, too. Her freshman auction outing was the painting “Princess” (2016), estimated at $6,000 to $8,000; it sold for $106,250 at Phillips New York in the spring of 2019. Six months later, her oil “Pas de Trois” (2018) went for $423,000 at Christie’s New York.

Some artists don’t even need two appearances to shine: The Kenyan painter Michael Armitage, 36, debuted with the 2015 oil “The Conservationists,” which was estimated at $50,000 to $70,000 and brought $1.52 million in November 2019.

The Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, also 36, was another who found huge success at a first auction: Estimated at $39,000 to $65,000, his 2019 work “The Lemon Bathing Suit” went for more than $880,000 in February at Phillips London.

Some better-known contemporary artists are not seeing these sky-high prices. Take Mel Bochner, who at 80 has been an acclaimed Conceptual artist for decades, and whose work has appeared on the auction block for more than 30 years. His auction record is a comparatively low $187,500.

According to David Galperin, head of Sotheby’s contemporary art evening auctions in New York, it’s not unheard-of for new names to attract attention. He pointed to the rise of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s career in the 1980s.

What’s different now, Mr. Galperin said, is that there are more buyers with more money: “The art market is so much bigger, and the buyers at that level are deeper and more global.”

Eye-popping prices are a result, especially when a signature work is on the market. Mr. Wong’s “Realm of Appearances,” for instance, is considered “the best of the best” of his works, Mr. Galperin said.

It takes only two bidders working against each other to make a record, and the auction market is famously unpredictable. “It’s not a meritocracy,” said the art adviser Liz Klein, of Reiss Klein Partners.

But those prices aren’t flukes, either. For “The Realm of Appearances,” there was substantial interest: 59 bidders registered. Fans of Mr. Wong’s work will have another chance to bid on it Oct. 7, when his “Shangri-La” (2017) is to be offered at Christie’s. The estimate is $500,000 to $700,000.

Scarcity matters in this equation. Once an artist has died, “that means a finite pool of material,” said Emily Kaplan, a senior specialist in postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s.

That may have been a factor for Mr. Wong’s work, and may also have affected the market rise of the painter Noah Davis, who died in 2015 at 32.

In May of 2019, his first sale at auction, “Bust 3” (2010), went for $47,500, more than three times the high estimate. In March of this year, “In Search of Gallerius Maximumianus” (2009) went for $400,000, five times its high estimate.

Ms. Kaplan said there was not a “one size fits all” model to explain different market flare-ups. But she did see an aesthetic commonality among many of the newly hot artists, who tend to depict things in the real world.

“In general, tastes have shifted to a figural style,” Ms. Kaplan said, adding, “It’s not just a pandemic phenomenon.”

Ms. Klein agreed, adding that the graphic painting style of Mr. Party and Ms. Curtiss had a wide appeal. And anyone who likes it can bid for it.

“The auction system is very democratic, and if you have the money, you can pay to play,” Ms. Klein said, contrasting that with the galleries who develop and nurture artist careers. They can be picky about whom they sell to, with an eye to placing an artist’s work in a good collection.

In market terms, success breeds more success. “There’s a whole group of collectors who only look at a work if it’s of a certain value,” said Jean-Paul Engelen, a deputy chairman at Phillips auction house. “People won’t look at a Julie Curtiss when it’s $5,000. But they will look when it’s $100,000.”

Mr. Engelen said that such interest also “means the gallery has done a good job” in terms of promoting their artist.

But high prices can have downsides, he added. “Your strength is your weakness,” Mr. Engelen said. “It’s great that your work is valuable. On the other side, there’s a danger element: If you’re the flavor of this month, you may not be two months later.”

Galleries are very wary of the same phenomenon. Marc Payot, the president of Hauser & Wirth, said his role was partly to give “protection” to young artists; he has represented Mr. Party since 2019.

“When the market of a younger artist goes sky-high at auction, and there’s no institutional support for that person,” Mr. Payot said, referring to museum shows or collections, “there’s a danger that it’s just speculation.” He added, “We hope that a market grows over the long term — but steadily.”

Some galleries have introduced contractual restrictions for buyers, to limit their ability to “flip” a work on the open market. They might require that the selling gallery be given the first crack at buying it back for a period of time.

The players who often don’t directly benefit from skyrocketing prices on the secondary market, like at auctions, are the artists themselves.

“People say, ‘You’re doing well,’ and I say, ‘Not as well as you think,’” said Ms. Curtiss, 37, who is based in New York. She has been put in an unusual position: being famous for her auction prices.

“I would rather the coverage be about my work,” she said.

Ms. Kaplan and Mr. Payot both noted that big auction prices inevitably bolstered the prices of an artist’s primary sales in galleries, too.

“To complain would seem ungrateful,” Ms. Curtiss said. She noted that for certain secondary sales of her work in Britain, she gets a small royalty based on local laws entitling her to an “artist’s resale right.”

In the initial instance of a surprisingly high auction record for her work, “it was crazy at first,” Ms. Curtiss said of her reaction. “But like anything, you get used to it.”

Ultimately, her way of handling the issue is to simply ignore it, given that she has no control over the matter.

“It doesn’t change my practice,” Ms. Curtiss said. “I keep doing my art.”