COVID-19 finds Blacks, Latinos eyeing med school to help their own

[ad_1]

The coronavirus pandemic shines a light on a systemic problem: racial bias in health care.

Wochit

Miriam Cepeda watched helplessly as her grandfather, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic who was sick with COVID-19, resisted pleas last March to go to the hospital.

“He told us he had sad memories of hospitals back home and he just didn’t trust the medical system,” said Cepeda, 19, whose grandfather later passed away from COVID. “For a lot of minority communities, going to the doctor isn’t our first choice or solution.”

Cepeda, of New York City, hopes to change that. The Columbia University sophomore plans to apply to medical school in a few years so she can serve patients of color, whose healthcare inequities have been highlighted by a virus that has sickened and killed people of color in disproportionate numbers.

Cepeda is among a growing number of Americans who are embracing medical school in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Applications to medical school for this coming fall are up 18%, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents 155 U.S. institutions. Some schools have seen 30% jumps. And many school officials specifically note that the number of applicants from traditionally underrepresented Americans is helping to drive the surge.

Miriam Cepeda, 19, of New York hopes to head to medical school after wrapping up her college career at Columbia University. (Photo: Courtesy of Miriam Cepeda)

Black, Latino and Native Americans are nearly three times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many of the healthcare workers on the pandemic’s dangerous front lines are Black, Latino or Asian. Despite those risks, Cepeda said her generation is inspired to help.

“My sense is a lot more Blacks and Latinos I know are interested in medicine due to this crisis,” said Cepeda. “We’re seeing things happen to those we know and are wondering, how do we get into positions where we can better help our people?”

For many students of color, everything from the cost of medical school to the lack of role models in the field are hurdles that administrators are trying to overcome by more actively pursuing non-white collegians and ramping up scholarship opportunities.

In some cases, keeping tuition costs low goes a long way to keeping med school an option for students who might otherwise be left out considering such school loans can hit $250,000 and more. The efforts are needed as Black doctors remain in short supply. Only around 5% of physicians nationally identify as such, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“Medical schools increasingly realize the importance of training a diverse physician workforce that can care for a diverse nation,” said Geoffrey Young, the association’s senior director of student affairs and programs. “We still have a lot of work to do on that.”

At Texas Tech University Health Science Center in Lubbock, one year of medical school costs around $17,000, among the lowest in the nation when compared to Harvard Medical School’s annual tuition of around $65,000. The school also offers a three-year accelerated program for those going into family medicine.

“What we’re seeing in our applications has a lot to do with the crisis showcasing the obvious importance of physicians to local communities,” said Dr. Steven Berk, who serves as dean of the Texas Tech medical school.

Berk reports that while his school saw a 20% jump in overall applications for the coming fall class, the number of Latino and Black applicants was up 30% and 43% respectively.

Marcus Gonzalez, who is in medical school in Lubbock, Texas, aims to return to his rural community north of Dallas to practice and help other Latinos. (Photo: Courtesy of Marcus Gonzalez)

Modest tuition cost was critical to realizing the dream of Marcus Gonzalez, 24, a second-year med student at Texas Tech and president of the student government association. He said there’s been an uptick in the number of students asking him about medical school, particularly those from underrepresented communities.

“As a Latino, it is so refreshing to see,” said Gonzalez, whose family back in Little Elm, Texas, just north of Dallas, has worked for generations in the fields. He is the first aspiring to a professional career. “Hopefully as I mentor more kids, they’ll see they, too, can be doctors. Patients appreciate seeing doctors who look like them.”

COVID-19 may have Watergate-like effect on med school interest

Conversations with a national cross-section of medical school administrators and students, as well as collegians hoping to become doctors, suggest the pandemic broadly may create a watershed moment for medicine.

Observers say much the way the ‘70s Watergate presidential crisis drove many into journalism and 9/11 saw military enlistments surge, COVID-19 has burnished the medical profession by putting a spotlight on the heroism of doctors, nurses and experts such as infectious disease veteran Anthony Fauci, whose scientific updates to the nation were hamstrung by a dismissive Trump administration.

Some wonder if Fauci, who is chief medical advisor to President Joe Biden, might become responsible for more students going into his specialty.

“It reminds me a bit of when I was going into med school in the ‘90s, and so many people seemed to be doing so in order to cure AIDS, which was rampant,” said Dr. Kristen Goodell, associate dean of admissions at the Boston University School of Medicine.

The school is poised to hold a symposium with a goal of raising funds for the Rebecca Lee Crumpler MD Scholarship, named in honor of the nation’s first Black woman to earn a medical degree in 1864. The scholarship will be aimed primarily at Black and Latino students.

Goodell said the surge in med school applications from students of color “will only improve the educational experience for everyone since it’s a known fact that in any field a diversity of backgrounds and experiences makes solving complex problems easier.”

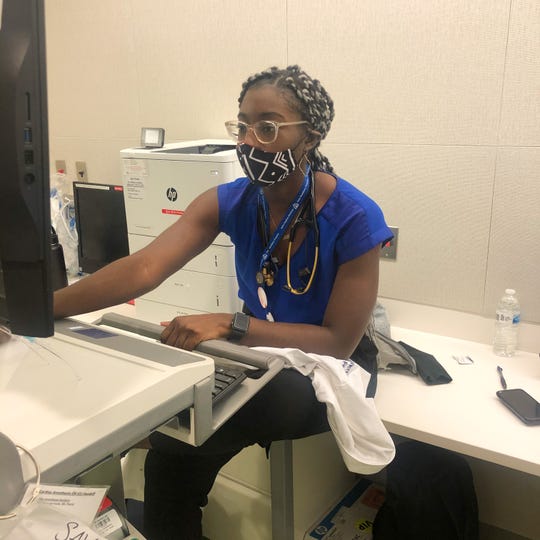

Christle Nwora, who is an internal medicine and pediatrics resident at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said Black and Latino Americans are needed not only as doctors but also as hospital administrators, to help build confidence in the system among those from marginalized backgrounds. (Photo: Courtesy of Christle Nwora)

If the pandemic has shown anything it is that a range of health-related specialties is needed to repair and run a national system rife with cracks, said Christle Nwora, a first-year medical school resident in internal medicine and pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“The younger students I speak with are showing interest in everything from medicine to public health communications,” said Nwora, who did her undergraduate and med school studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

“I love my patients, but health care is so much more than my 15 minutes with them,” she said. “You need businesses minded people, too, people to run hospitals, vaccine distribution. There’s so much.”

To be sure, this year’s jump in applicants is likely the result of a combination of factors that include some students being unable to spend a gap year doing in-person research because of COVID-19 restrictions; others taking advantage of no-cost, online interviews to apply to more schools than normal; and a few simply seeing a straight path to guaranteed income at a time when jobs are hard to come by.

“At this point, these are all hypotheses,” said Dr. Robert Mayer, faculty associate dean for admissions at Harvard Medical School. “But what is real is the increased number of candidates which has kept those of us involved with medical school admissions unusually busy this recruitment season.”

For some applicants, the health crisis of the past year was integral to their decision. Shaheer Khan, 21, grew up appreciating his Pakistani-born father’s community role as a doctor in Keller, Texas, near Fort Worth. But he didn’t really consider a career in medicine.

“During the pandemic, that changed,” said Khan, who is in his third year at the University of Texas at Austin and plans to apply to medical school next year. “I saw how much courage my dad showed, how he had to make sense of so much information flooding in, and do so to help guide patients and family and friends alike.”

US needs 133K more doctors by 2033

The boom in med school interest arrives just as experts predict a shortage of doctors across the United States, where the national population is aging while also becoming more diverse.According to the medical college association, there will be an expected shortage of 133,000 physicians by 2033.

An explosion of applications to medical school may sound encouraging, but for the moment it simply means there is greater competition for a limited number of spots. That means students from underrepresented communities need to become an even greater priority for med schools.

“Each institution will have to answer the question of how they’re helping to shore up the pipeline of doctors, especially when it comes to students of color,” said Dr. Michelle Albert, associate dean of admissions for the University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine, where nearly half of students are non-white and half are female.

Albert, who is a cardiologist and Black, is inspired by what appears to be a growing interest in medicine especially on the part of students of color. But she said schools have a long way to go to deliver to those students.

“I would hope these times would galvanize people, but the reality as a Black woman who went through this process is that it’s a long-distance to travel between the dream and reality,” she said. “One thing everyone in our profession has to work on is minimizing any structural barriers that make this career more challenging.”

A patient receives treatment in the emergency room at Roseland Community Hospital in Chicago. About one-third of the patients that arrive in the ER at Roseland display symptoms of COVID-19. The Roseland neighborhood, on the city’s far south side, is 95% Black. (Photo: Scott Olson, Getty Images)

The numbers often look daunting for those aspiring to a career in medicine.

“This year was a record for us, with 8,395 applications for 100 spots, a 26% increase,” said Dr. Ngozi Anachebe, who oversees admissions and student affairs at Atlanta’s Morehouse School of Medicine, one of a few historically Black colleges and universities stepping up efforts to build the ranks of doctors of color.

Anachebe said Morehouse, which also has an undergraduate college, has an explicit mission to “make sure a career in medicine is not beyond the reach of poor students, because they are the ones most likely to go back to where they’re from and help.”

There is a range of efforts afoot to ensure that medical school remains an option for those in difficult socioeconomic straits.

The Association of American Medical Colleges not only offers financial assistance with the cost of med school applications to those who qualified, but their strategic plan includes addressing unconscious bias and systemic racism by helping schools train officials to broaden their vision when it comes to applicants.

“Schools have to acknowledge that until as a nation we address access to quality healthcare, we’ll have a challenge creating a diverse population of medical professionals,” said Young, the association’s student affairs director.

At Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, administrators are focused not only on stepping up recruiting from historically Black colleges and universities, but also ensuring that once enrolled, future doctors of color “are provided with mentors to help them along the way,” said Dr. Anne Armstrong-Cohen, senior associate dean for admissions.

“We feel we’ve always had a focus on diversity at Columbia, but what happened with the pandemic is it has made this issue a real focus,” said Armstrong-Cohen.

$100 million could boost Black doctor ranks

Sometimes help comes from the outside. At Howard University in Washington, D.C., one of the nation’s preeminent schools focusing on Black students, administrators ramped up their recruiting efforts after the Bloomberg Foundation announced last fall a $100 million donation over four years to four historically Black colleges and universities.

The donation provides up to $100,000 in tuition relief for enrolled med school students at Howard, as well as at Morehouse School of Medicine, Meharry Medical College in Nashville, and Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles.

Sydni Johnson, 23, plans to attend medical school this fall, where she hopes to focus on pediatrics and oncology. Johnson, from Houston, said despite the profession’s cost and sacrifices, she is eager to give back to her community. (Photo: Courtesy of Sydni Johnson)

“We’re excited that a large number of our applicants seem to be interested in primary care in underserved communities,” said Dr. David Rose, Howard’s dean of student affairs and admissions. “But we always want to make sure they mean that, and in fact, many have shown a commitment to that even before the pandemic.”

That would describe Sydni Johnson, 23, of Houston, who is busy deciding on a medical school where she plans to focus on pediatric oncology. She has wanted to be a doctor since high school, and volunteered in hospitals while attending Prairie View A&M University, a historically Black college in Prairie View, Texas.

Although Johnson said the way doctors and nurses have stayed true to the Hippocratic Oath throughout the pandemic, often enduring endless hours and suffering PTSD, has “only motivated me more to provide good care to people, especially those communities that the pandemic has affected in a very adverse way.”

Johnson, whose father works at a chemical plant and whose mother works for a janitorial service, credits a range of mentors and financial aid grants for keeping her doctor dream alive.

“I know it seems hard to imagine, but I would really encourage my peers to think seriously about going into medicine,” she said. “Sure, it requires a lot of sacrifice, but we are supposed to be there for people.”

That sentiment seems in great supply among students of color hoping to become doctors, inspired by the heroic work of the profession in the past year as well as frustrated by the medical injustices visited upon marginalized communities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mischael Saint-Sume, who recently graduated from Howard with a degree in biology and is waiting to hear back from a range of med schools, said he always knew medicine was his destiny growing up in Opa-locka, Florida, a low-income city north of Miami.

“When you go to see doctors who aren’t the same color, there’s often this feeling that you’re not being heard,” said Saint-Sume, 21, who hopes to open a surgery clinic serving the mostly Haitian and Latino hometown of his youth.

“On the other hand,” he said, “when it’s someone who looks like you and knows your community and its issues, it encourages you to seek better health. Isn’t that what it’s all about?”

Follow USA TODAY national correspondent Marco della Cava: @marcodellacava

Read or Share this story: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2021/01/30/covid-19-finds-blacks-latinos-eyeing-med-school-help-their-own/4266815001/