Enslaved, Terrorized, Disenfranchised: Black Americans Still Found Ways to Change America

[ad_1]

When Baker, Mallory and Townsend rowed their stolen skiff across the James River in 1861, nearly 90 percent of African-Americans were enslaved, and most of the nearly quarter million who resided in Northern “quasi freedom” were disenfranchised. Yet, as both Baumgartner and Wells show, Black movement against the laws and institutions that enslaved them affected American politics far more than any ballot cast or Electoral College vote.

The United States’ early-19th-century border with New Spain — a vast expanse of diverse climate and varying geography spreading from present-day Florida to California and south through the Gulf Coast and Yucatán Peninsula — was a particularly porous boundary between slavery and freedom. Relying on Mexican and American archives, including congressional records and letters from the period of the Mexican-American War (1846-48), Baumgartner demonstrates how enslaved people fled to Mexico, where they invoked the republic’s contested antislavery laws to claim their freedom and, in doing so, contributed to the political wrangling over slavery’s future in the United States.

New Spain provided legal protections for the fugitives, despite a long history of African and Indigenous enslavement throughout the Spanish empire. Siete Partidas, a 13th-century legal code that protected enslaved people from mistreatment, was grounds for African-American sanctuary in the face of slaveholding America’s most brutal forms of control: branding, maiming, starvation. In the hands of a less meticulous scholar, the notion that fugitive slaves invoked Siete Partidas when they arrived in New Spain after fleeing the horrors of Louisiana or Mississippi could come across as matter-of-fact. Yet there is nothing matter-of-fact, Baumgartner argues, about the conflict between white plantation owners, perpetually hungry for fresh cotton land in the Southwest, and the antislavery laws of the Mexican republic. To show this, she enlists the heartbreaking and carefully researched stories of escaped slaves themselves.

In 1820, when Moses Austin, the owner of a lead mine near St. Louis, petitioned Spanish authorities for permission to settle 300 Americans in the New Spanish province of Téjas, he was accompanied, for part of his journey, by a Louisiana slave owner, James Kirkham. Kirkham carried his own petition to the provincial capital of San Antonio de Béxar for the return of three enslaved people who had escaped from his plantation the year before.

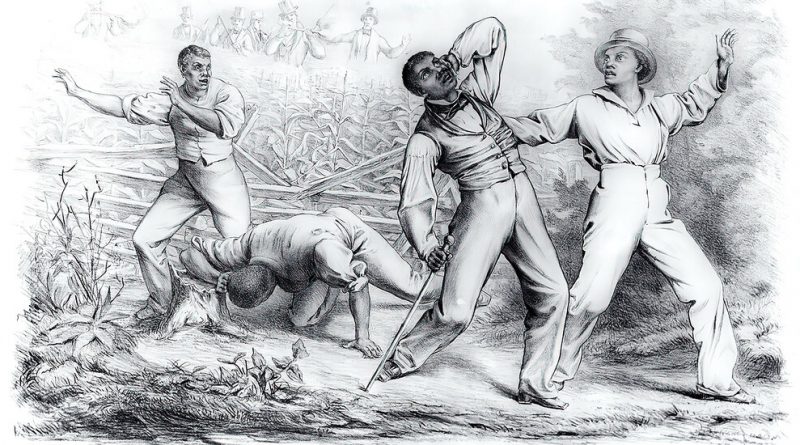

Other scholars have framed Austin’s journey as the starting point for Anglo settlement in Téjas, a prelude to the supposedly exceptional story of Austin’s more celebrated son, Stephen Fuller Austin, known as “the Father of Texas,” who carried out his father’s mission, and to the two decades of political conflict that led to the annexation of Texas by the United States. But Baumgartner situates this first step in the incursion into Mexico of norteamericanos within the 1819 escape of the enslaved people: Martin, Fivi and Richard, from Kirkham’s plantation, and Samuel, from a neighboring one, who together fled more than 100 miles west to Nacogdoches. One of the fugitives had attempted escape before, and bore the terrifying brand “R” (for runaway) on his cheek, a detail that Baumgartner renders with the same novelistic flair that she does the slaves’ harrowing journey on to Monterrey, 600 miles south, where the military commander in Nacogdoches, reluctant to emancipate them himself, sent them to plead their case before a judge. In Monterrey, they invoked the Siete Partidas and were eventually freed.

Baumgartner’s placement of fugitive slaves at the center of this story is not merely cosmetic. The fact that the commander in Nacogdoches wrestled with whether to grant them freedom, despite the legal precedent for doing so, shows how slavery, emancipation and empire were constantly renegotiated based on enslaved people’s movements across geographical and political boundaries. The commander’s hesitation arose from fear of American reprisals: Spain had failed to stop the United States’ violent incursions into Florida under the leadership of the future president Andrew Jackson, who, in 1816, attacked the so-called Negro Fort on the Apalachicola River. Like the rest of New Spain, Florida had long been a refuge for enslaved Africans; Spanish law protected them at the Negro Fort as surely as it shielded Kirkham’s slaves in Monterrey. But Jackson and his soldiers, determined to remand the Negroes on the Apalachicola River and subdue the Seminole Indians with whom they were allied, continued to occupy Florida as the Spanish empire collapsed from Venezuela to New Grenada.

Thus, Baumgartner argues, the four fugitives’ arrival in Nacogdoches, and their successful petition for freedom in Monterrey, had a significant effect on relations between the slaveholding United States and what eventually became antislavery Mexico. James Kirkham returned to Louisiana without his slaves, and Moses Austin died in Missouri soon after he was granted permission to bring Anglo settlers to Téjas. Yet his plan was eventually fulfilled by his son and other white Americans, many of whom brought slaves with them, with the result that political crisis characterized Mexican-American diplomacy every time Black people crossed the border.

[ad_2]

Shared From Source link Arts