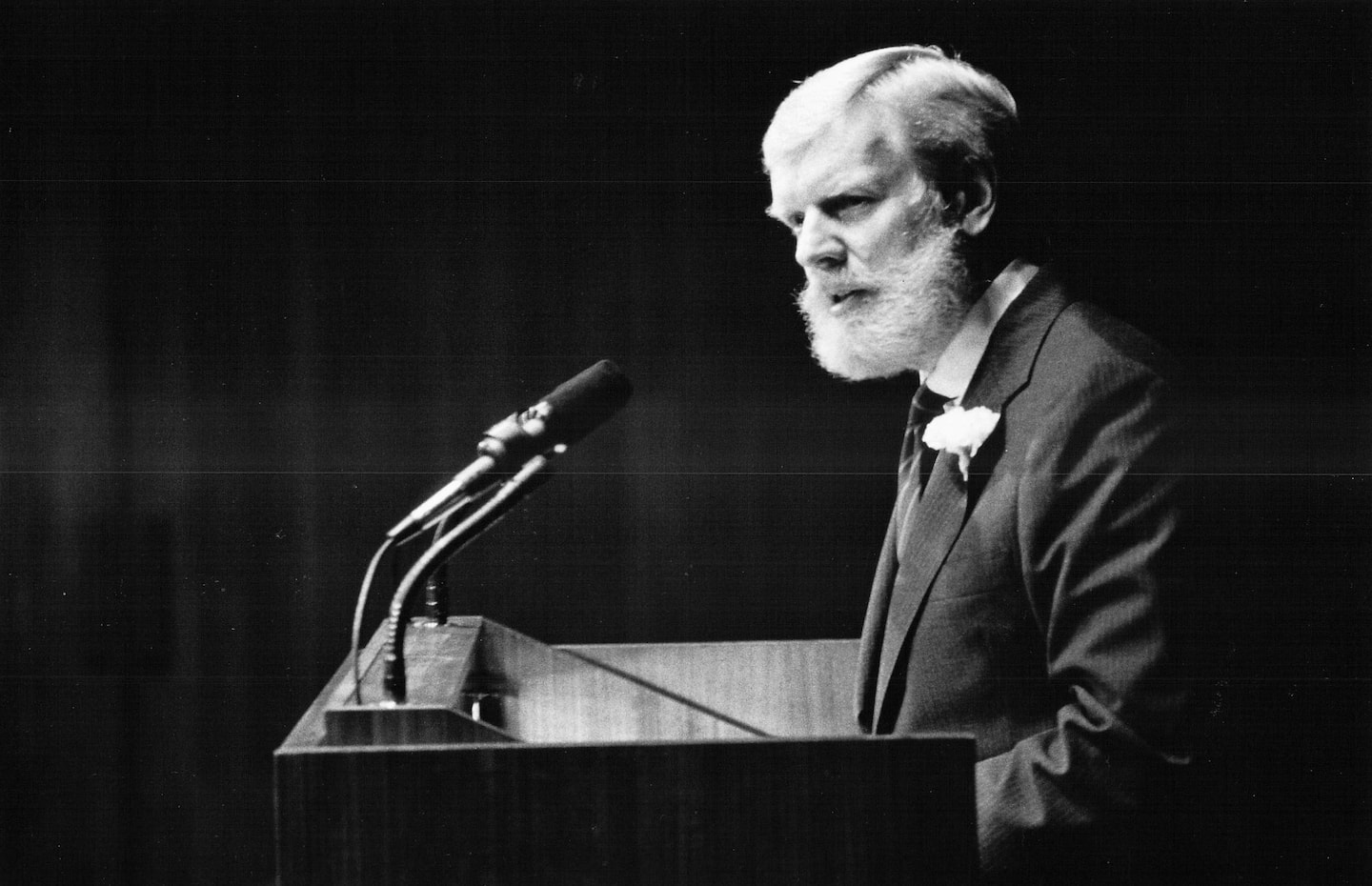

John Naisbitt, futurist and best-selling author of ‘Megatrends,’ dies at 92

[ad_1]

Mr. Naisbitt (pronounced NEZ-bit), a onetime public relations executive and federal official, became an independent business analyst in the late 1960s, first in Chicago and later in Washington.

Spotting trends in newspapers and magazines, he summarized his findings in reports for businesses, research groups and libraries. He struggled for years, declaring bankruptcy in the late 1970s — and pleading guilty to bankruptcy fraud — before “Megatrends” made him an international star of futuristic studies.

In the book, Mr. Naisbitt focused on 10 major trends he believed were reshaping American commerce and society. His first observation, long before personal computers had become commonplace, was that the country was moving from an industrial and manufacturing society to an information society.

He predicted that technology companies would foster a new industrial model, with ideas rising up from workers rather than being imposed by executives at the top of the corporate ladder. As jobs flowed to the Sun Belt, Mr. Naisbitt said technology workers would become hungry for a social connection with other people — a phenomenon he called “high tech/high touch” and used as the title of a later book.

“We must learn to balance the material wonders of technology,” he wrote in “Megatrends,” “with the spiritual demands of our human nature.”

Some of Mr. Naisbitt’s ideas didn’t quite hit the mark, including the suggestion that businesses and individuals would come to value long-term planning over short-term gain. Still, the cheery optimism of “Megatrends,” in which technology would benignly break down social and financial barriers, had such widespread appeal that the book sold more than 8 million copies around the world and stayed on bestseller lists for years.

“My God, what a fantastic time to be alive!” Mr. Naisbitt wrote at the conclusion of “Megatrends.”

Critics and scholars didn’t always share his wide-eyed enthusiasm. Journalist Karl E. Meyer, reviewing the book in the New York Times, wrote that “Mr. Naisbitt has produced the literary equivalent of a good after-dinner speech.”

Some said he was merely repackaging common knowledge as a feel-good panacea for people already on the road to success. Others noted that workers without college degrees or who were not adept with computers were left out of Mr. Naisbitt’s rosy portrait of the future.

But countless readers and corporate leaders took heart in his message of better living through technology. His consulting firm prospered, President Ronald Reagan invited him to the White House, and he considered British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher a friend.

He sometimes gave two speeches a day to business groups, at a reported $15,000 per appearance. He had a knack for snappy one-liners, such as “Trends, like horses, are easier to ride in the direction they are already going” or “We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge.”

Mr. Naisbitt’s research method, known as content analysis, derived from his reading of Bruce Catton’s Civil War histories, which relied heavily on reports from contemporary newspapers. Allied intelligence organizations also studied local newspapers during World War II to gauge public behavior and moods.

Mr. Naisbitt used the same technique when he opened his first consulting firm in the 1960s. By the early 1980s, when he was running the Naisbitt Group in Washington, his researchers were reading 250 newspapers and dozens of magazines a day. He paid particular attention to what he called five “bellwether states” known for social change — California, Florida, Washington, Colorado and Texas.

“Our approach has to do with the notion that change starts locally, from the bottom up,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. “That’s why newspapers are so important to us: No one else comes closer to chronicling what is happening.”

When scholars complained that Mr. Naisbitt’s methods were superficial and arbitrary, he countered that by the time an academic journal spotted a trend, it was already out of date.

They foresaw the growing prominence of women in the workplace, the rising economic power of Asia and a trend toward working from home. They also predicted that “the arts will permeate mass culture as never before, replacing sports as our dominant leisure activity.”

“On the threshold of the millennium, long the symbol of humanity’s golden age,” they wrote, “we possess the tools and the capacity to build utopia here and now.”

Critics noted, however, that Mr. Naisbitt’s forecasts failed to notice the coming collapse of the savings and loan industry in the 1980s, the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, the spread of AIDS, the 1987 stock market crash or the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

John Harling Naisbitt was born Jan. 15, 1929, in Salt Lake City. His father was a security guard and bus driver, his mother a seamstress.

Mr. Naisbitt, whose family struggled through the Great Depression, dropped out of high school to join the Marine Corps. He used the G.I. Bill to attend the University of Utah, graduating in 1952.

He was a publicist and speechwriter for Eastman Kodak in Rochester, N.Y., before moving to Chicago, where worked for the Great Books Foundation, National Safety Council and the public relations department of Montgomery Ward.

He first came to Washington in 1963 to work at the U.S. Education Commission and later as an assistant to John W. Gardner, the secretary of the old Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Mr. Naisbitt returned to Chicago in 1966 and founded his first research firm two years later, publishing reports and newsletters for major companies, foundations and government agencies.

He moved to Washington in the mid-1970s, founding a nonprofit called the Center for Policy Process. In 1977, Mr. Naisbitt declared bankruptcy, saying his only assets were $5 and a tennis racket. A court found that he had not included some art objects in the inventory, and he was ordered to sell them. He was found guilty of bankruptcy fraud in 1978 and was sentenced to 200 hours of community service and three years’ probation.

Four years later, the success of “Megatrends” made Mr. Naisbitt a mega-millionaire. His corporate clients included General Motors, AT&T and Merrill Lynch, and he had homes in Telluride, Colo., and Cambridge, Mass.

He moved to Austria after his third marriage in 2000 and increasingly focused his attention on Asia, which he said “will become the dominant region of the world: economically, politically, and culturally.”

His most recent book, “Mastering Megatrends,” written with his wife, Doris Naisbitt, was published in 2019.

His marriages to Noel Senior and Patricia Aburdene ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife, Doris Dinklage Naisbitt, a former Austrian publishing executive, of Velden am Wörthersee; five children from his first marriage, James Naisbitt of Chicago, Claire Marcil Schwadron of Takoma Park, Md., Nana Naisbitt of Durango, Colo., John S. Naisbitt of Woodridge, Ill., and David Naisbitt of Springfield, Va.; a stepdaughter, Nora Rosenblatt of Hamburg; and 13 grandchildren.

Despite his perennial optimism, Mr. Naisbitt recognized that technology sometimes produces new social problems, from violent video games to a lack of engagement with nature and other people.

“Americans are intoxicated by technology,” he wrote in his 1999 book “High Tech/High Touch” with his daughter Nana Naisbitt and Doug Phillips, which “is squeezing out our human spirit.”

Instead of spending thousands of dollars on elaborate gaming systems for their children, Mr. Naisbitt suggested that for $1 “you can go get them a ball.”

[ad_2]

Source link