NGV Triennial: a bold and urgent artistic intervention, studded with beauty and calm | Art and design

[ad_1]

The Residences at NGV International promises high quality fittings and top of the range brand name appliances. But the walls are flimsy, the ceilings too low and the appliances are grotesquely outsized – there’s even a toilet seat you need to climb a ladder to reach.

It’s not a suite for a new inner city development, though you may initially be fooled; it’s an artwork by Swiss architects BTVV that riffs off Melbourne’s apartment boom, and our interest in high-end, brand name appliances over good design principles.

This work, located on the ground floor of the National Gallery of Victoria’s St Kilda Road premises, is one of the first that visitors to the NGV’s second triennial will encounter, but not the only one that will bulldoze new neural pathways in your brain. Up the escalator is Planet City 2020: a video installation by Liam Young that examines design from a wildly creative place, and sets the mind on the path of imagining what the near future may hold. Can we design our way out of our current environmental crisis? And if so, what would that look like? His vision is a ragged city made of old things, but it is also optimistic and bold: it’s a future in which we’ve learned to coexist more equitably with nature.

The triennial is a colossal exhibition that engages the heart, as well as the head. Amid the big, bold, expensive acquisitions, the gallery is studded with moments of quiet beauty and calm.

Take the Salon et Lumière. Created by an in-house team at the NGV and working with the existing collection of more than 140 paintings and sculptures from the 19th century, it uses light and sound to create a modern experience that “embodies the clamorous power” of 19th-century art exhibitions in Paris. The room is captivating.

“I wanted to do something particularly magical in that space,” NGV director Tony Ellwood says.

He says it has already moved some early visitors to tears.

“People after lockdown are in a different state of mind and when they see something that elevates them, it’s a very emotive experience. And they have been starved of that experience.”

The NGV had been planning its follow-up to the inaugural 2017 triennial for more than three years. For Ellwood, that first triennial was a huge gamble that paid off in record attendance and rave reviews.

This time round, his gamble was to sit tight as the Covid-19 pandemic threatened to scuttle the entire thing.

“There were moments when I was in complete denial,” Ellwood says. “Two to three months ago, it seems like another lifetime. I had to believe it would work out, and with government and health advice, we barrelled ahead.”

Workarounds were found. Locally made materials were often more reliable than getting things shipped in by crate. The huge curatorial team liaised with artists via Zoom across time zones, works were installed with artists supervising via iPads, and socially distanced small teams put the show together.

Senior curator of contemporary design and architecture, Ewan McEoin, took Guardian Australia on a tour of the triennial before its opening. It’s no cakewalk. Almost 90 projects from 30 countries – including 33 works commissioned by the NGV to be added to its permanent collection – are spread over the gallery. They take up more physical space in the gallery than they did in 2017 too – we saw about 70% of the exhibition and still clocked in at almost two-and-a-half hours.

The triennial is organised around four themes: illumination, reflection, conservation and speculation. There is a preoccupation with the natural world, including species extinction, pollution, and the displacement of Indigenous communities. There’s also an exploration of the negative and positive potential of technology, from artificial intelligence to the selfie.

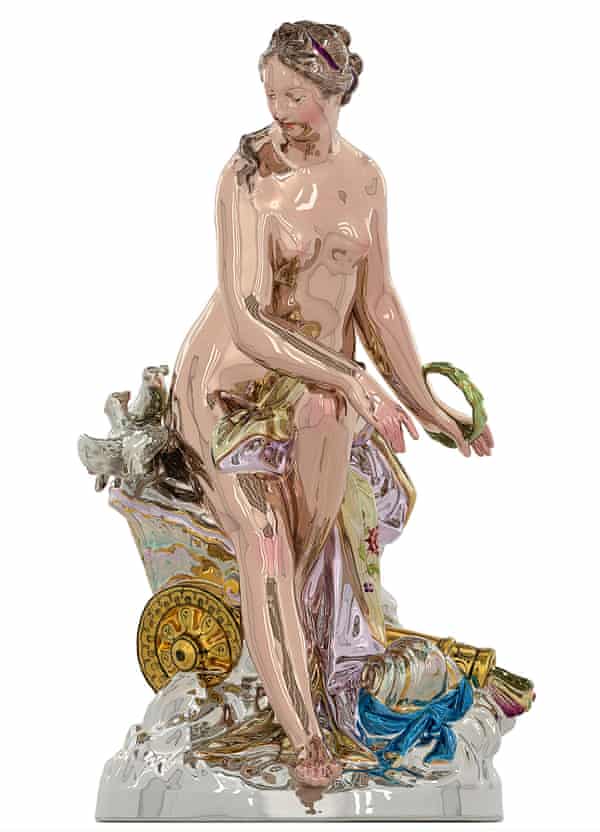

One of the headliners of the exhibition, and a major commission for the NGV, is Jeff Koons’ Venus 2016–20, part of the artist’s Porcelain series.

Based on an 18th century porcelain figurine by Wilhelm Christian Meyer, the oversized figure is an arresting, mirror-polished, stainless steel feat of engineering. You’re not allowed to touch it but you’ll want to, as you stare at it and see your distorted face staring back at you.

Ellwood says it’s “the kind of ambitious work we rarely see in Australia”.

“When Australians do travel, they do go to Moma or the Tate and experience contemporary art. They should be enjoying these international scale experiences in their own back yard as well.”

Then there’s the statement piece that dominates in the NGV foyer (where the much-loved reclining Giant Buddha was last time) – mind-boggling and awe-inspiring in a different way. Refik Anadol’s 10-metre Quantum Memories is a huge multimedia work that uses artificial intelligence to pull out every photo of the natural world on the internet – more than 200m images – and regurgitate the results into a swirling, moving tapestry. The work is ever-changing, depending on the data it pulls out.

“It’s the first true quantum artwork created and the largest digital artwork staged by the NGV,” says McEoin.

Work with this level of heft and urgency were part of Ellwood’s initial vision for the triennial. Victorian audiences don’t just want to see the old masters, he says, but also experimental and critical works that engage with issues we are facing right now.

“I felt we were a bit on repeat,” says Ellwood. “The big winter shows were very important but I felt that we could take more artistic and financial risks. My belief was there was a more substantive audience for contemporary art and design.”

There is also a transcendent beauty in the work of Dhambit Mununggurr. Her immersive installation, Can We All Have a Happy Life (2019 – 2020) is made up of 15 bark paintings and nine larrakitj (hollow poles) and was created in north-east Arnhem Land.

What is arresting about the work is the startling shade of blue Mununggurr uses – it seems to pulsate, it’s so vibrant. It’s a hue that’s not found in nature or subtracted from the ochre usually used in Indigenous art from the region. Mununggurr’s community’s cultural protocols for traditional painting meant she was only allowed to use a colour palette that could be drawn from the earth – until a car accident rendered her unable to do the work to extract pigment. She sought permission from the elders to use blue acrylics instead, which they gave.

Mununggurr is a true discovery for the gallery, who commissioned the work for their permanent collection.

“She had been rejected from art prizes,” says Ellwood, incredulous. “It’s a story about coming out of adversity after a severe accident … It’s profoundly beautiful.”

The triennial is not the sort of show that lets its viewers off easy, but it also shows possibilities: that it’s not too late, that we can reimagine how we live, that we can and must reconnect with the natural world.

Imbued with spiritual overtones, in the garden at the back of the NGV is work by celebrated French artist, JR – another major acquisition for the NGV – telling a very Australian story.

In February, JR visited Australia, and with a small delegation from the NGV, went to the Murray-Darling area of Menindee. Once there, he photographed elders and local farmers affected by drought and intensive water extraction. Those portraits have been set in stained glass windows constructed into an open air chapel. The experience is like visiting a secular church of (so far) unanswered prayers. A film also accompanies the work.

With Melbourne audiences emerging from a long lockdown and very hard winter, Ellwood and McEoin say they anticipate many visitors to the Triennial will find returning to the gallery quite emotive.

And because most of the rest of the world is locked down, this is the only major show in the world of its kind at the moment. “People globally in the art world are watching this show with interest,” says Ellwood.

It seems like a minor miracle that we get to see it at all.

• The NGV Triennial is showing at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, from 19 December until 18 April

[ad_2]

Shared From Source link Arts