Noviembre: explosive manifesto takes theatre to the streets | Political theatre

[ad_1]

Can theatre change the world? Not, you suspect, if it’s a ticketed performance watched from a red velvet seat with a glossy programme and an ice-cream. The guerrilla theatre-makers in the 2003 Spanish film Noviembre, directed by Achero Mañas, have a 10-point manifesto for the revolution they’re staging on the streets. All their performances are free and available to all, they accept no private or public subsidies, and only original material is presented. If you’ve acted for TV or film then forget it – you’re banned from Noviembre.

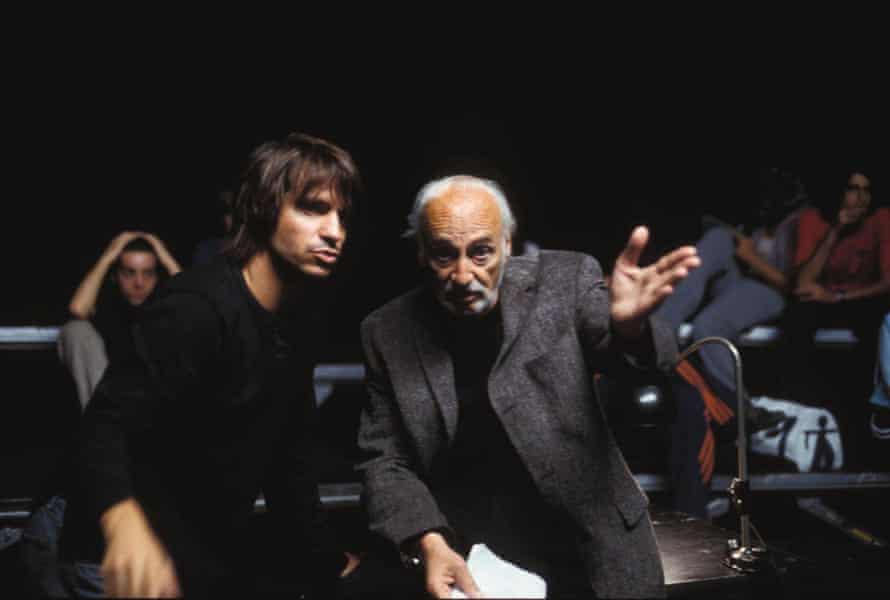

The group is led by Alfredo (Óscar Jaenada), who arrives in Madrid from Murcia in the late 90s to attend drama school. Alfredo auditions with a piece he has created for a homemade marionette but comes to believe it is his fellow actors who are treated like puppets by their tutor, Yuta (played by veteran Argentinian theatre legend Héctor Alterio). He resents Yuta’s expectation that actors will divulge their most personal secrets in service of a performance. Damning that approach as group therapy, he drops out to seek a more spontaneous relationship with the audience, who he believes should interact with the performance, not sit in the stalls like statues.

Mañas presents the film as if it is a documentary, with older versions of the main characters appearing as talking heads, reflecting on the ups and downs of the company who live together in a squat that they aim to turn into a cultural centre. This is not a mockumentary – we are never invited to laugh at their exploits. If anything, the tone is earnest and the company’s performances are named, dated and shown in lengthy episodes with the older actors’ reflections alongside. The documentary format invites us to seriously appraise the art of their street theatre and implicitly suggests that the company has left a legacy.

And these improvised performances are pretty thrilling – vibrant, provocative disruptions in public spaces that grip passersby. In The Hot Lady, a lascivious couple – him in a pierrot smock, her in red suspenders hitching up a dress – prowl around town. Happy Punks is a bass-slapping, drum-beating dance with commuters. For The Devil’s Cherubim, the troupe paint their bodies red and put on giant nappies then run rampant among shoppers. The bystanders’ expressions for many of these performances give the suggestion that they were filmed on the hoof.

Noviembre whet my appetite for a summer of open-air performance and what many predict will be a boom for outdoor theatre as the pandemic will bring limitations to indoor productions. The film makes a convincing case for the power of free outdoor arts, presented in democratic spaces, reaching audiences that may not usually visit the theatre. “The same people always see plays,” declares Alfredo, who isn’t interested in preaching to the converted; he wants to create spontaneous performance that brings with it unpredictable responses.

Rather like the company of travelling players in Shakespeare Wallah, Noviembre is conceived as an idealistic mission. The group see their performances as gifts to the public and audiences are surprised to find that no hat is passed around for donations. At the start, it is the form of their work that is expressly political – this is free theatre for all and art for art’s sake, without commerce entering the equation. But increasingly the content grows political, too. Art, they believe, should never be polite. But Mañas gives careful consideration to the ethics of performance that bursts, uninvited, into the lives of unexpecting audiences. What is the contract between these artists and audience? When does a diversion become a nuisance? How much disruption is society built to stand? Noviembre’s downfall begins with a misguided piece, named Shooting, in which they enact a murder on the street. Designed, they say, to help the public gain a greater understanding of terrorism, it wastes the precious time of the emergency services.

Mañas, who is the son of actor Paloma Lorena and playwright Alfredo Mañas, started out acting before becoming a director. His first feature, El Bola (Pellet, 2000), about a young boy who is abused at home, won four Goya awards in Spain. His debut and Noviembre sensitively depict the dynamic in groups of outsiders, feature superb performances and have a sense of authenticity and earnestness. Mañas strikes me as a true believer in the power of art – the film ends by paraphrasing a quote from the writer Gabriel Celaya, who called poetry “a weapon loaded with the future” – and he practises what Noviembre preach: you can watch the film, for free, on his YouTube channel.