Pediatric Doctors Group Apologizes for Racist Past Toward Black Physicians

[ad_1]

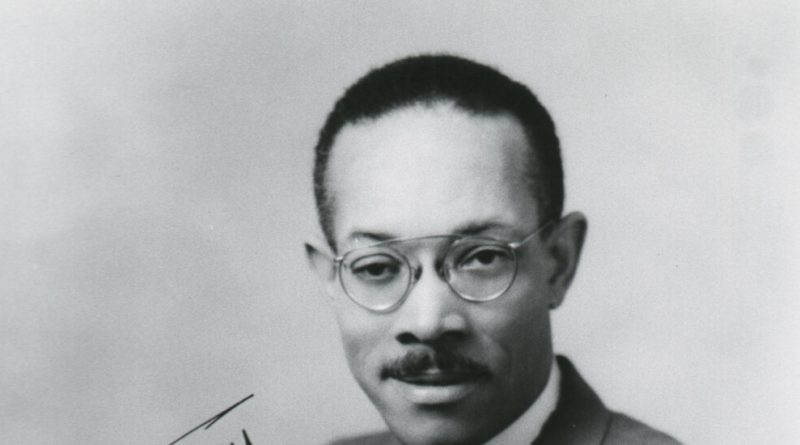

Dr. Roland B. Scott was the first African-American to pass the pediatric board exam, in 1934. He was a faculty member at Howard University, and went on to establish its center for the study of sickle cell disease; he gained national acclaim for his research on the blood disorder.

But when he applied for membership with the American Academy of Pediatrics — its one criteria for admission was board certification — he was rejected multiple times beginning in 1939.

The minutes from the organization’s 1944 executive board meeting leave little room for mystery regarding the group’s decision. The group that considered his application, along with that of another Black physician, was all-white. “If they became members they would want to come and eat with you at the table,” one academy member said. “You cannot hold them down.”

Dr. Scott was accepted a year later along with his Howard professor, Dr. Alonzo deGrate Smith, another Black pediatrician. But they were only allowed to join for educational purposes and were not permitted to attend meetings in the South, ostensibly for their safety.

More than a half-century later, the American Academy of Pediatrics has formally apologized for its racist actions, including its initial rejections of Drs. Scott and Smith on the basis of their race. The statement will be published in the September issue of Pediatrics. The group also changed its bylaws to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, religion, sexual orientation or gender identity.

“This apology is long overdue,” said Dr. Sally Goza, the organization’s president, noting that this year marks the group’s 90th anniversary. “But we must also acknowledge where we have failed to live up to our ideals.”

Dr. Goza said in an interview that the group learned from the example of another organization that confronted its racist past: the American Medical Association.

The American field of medicine has long been predominantly white. Black patients experience worse health outcomes and higher rates of conditions like hypertension and diabetes. Black, Latino and Native Americans have also suffered disproportionately during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the last decade, some medical societies and groups have released statements recognizing the role that systemic racism and discrimination played in driving these health disparities. Implicit bias affects the quality of provider services: Living in poverty limits access to healthy food and preventive care.

After the killing of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police, in late May, a flood of medical groups released statements on racial health disparities: the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, the American College of Cardiology, the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Psychiatric Association and more. The American Public Health Association released a statement recognizing racism as a “public health crisis.”

But few medical organizations have confronted the roles they played in blocking opportunities for Black advancement in the medical profession — until the American Medical Association, and more recently the American Academy of Pediatrics, formally apologized for their histories.

The A.M.A. issued an apology in 2008 for its more than century-long history of discriminating against African-American physicians. For decades, the organization predicated its membership on joining a local or state medical society, many of which excluded Black physicians, especially in the South. Keith Wailoo, a historian at Princeton University, said the group chose to “look the other way” regarding these exclusionary practices. The A.M.A.’s apology came in the wake of a paper, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, that examined a number of discriminatory aspects of the group’s history, including its efforts to close African-American medical schools.

For some Black physicians, exclusion from the A.M.A. meant the loss of career advancement opportunities, according to Dr. Wailoo. Others struggled to gain access to the postgraduate training they needed for certification in certain medical specialties. As a result, many Black physicians were limited to becoming general practitioners, especially in the South. Some facilities also required A.M.A. membership for admitting privileges to hospitals.

By 1964, the A.M.A. changed its position and refused to certify medical societies that discriminated on the basis of race, but persistent segregation in local groups still limited Black physicians’ access to certain hospitals, as well as opportunities for specialty training and certification.

“Physicians are no different from other Americans who harbor biases,” said Dr. Wailoo, whose research focuses on race and the history of medicine. “We expect doctors to speak on the basis of science, but they’re embedded in culture in the same way everyone else is.”

The A.M.A. also played a role in limiting medical educational opportunities available to Black physicians. In the early 20th century, before the medical field held the same prestige it does today, the A.M.A. commissioned a report assessing the country’s medical schools for their rigor. The report, by educator Abraham Flexner, deemed much of the country’s medical education system substandard. It also recommended closing all but two of the country’s seven Black medical schools. Howard and Meharry were spared.

As the field became more exclusive, it also became more white, according to Adam Biggs, a historian at the University of South Carolina. “When we talk about how modern medicine came to define what it means to be a modern practitioner, it was deeply rooted in race,” Mr. Biggs said. “Segregation was embedded in the pipeline.”

Between its restrictions on medical education and its exclusionary membership, the A.M.A. played a role in cultivating the profession’s homogeneity, which it acknowledged in its 2008 statement. It has since appointed a chief health equity officer and established a center for health equity. Dr. Goza said that the A.M.A.’s example helped spur the American Academy of Pediatrics to confront its own history.

There have been some historical examples of efforts to confront racism in the medical field. In 1997, President Clinton apologized for the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study conducted between 1932 and 1972, a quarter-century after it was first exposed by The Associated Press. In the early 21st century, a number of state attorneys general apologized for the forced sterilization of Black, mentally ill and disabled people, which began in the early 1900s.

But some of the field’s future leaders are now demanding change on medical school campuses.

Dr. Tequilla Manning, a family medicine resident in New York, graduated from University of Kansas Medical Center three years ago. As a medical student, she conducted a research project on Dr. Marjorie Cates, who became the school’s first Black female graduate in 1958. She began to draw parallels between Dr. Cates’ experience of discrimination on campus and her own.

Before graduating in 2017, she gave a presentation on Dr. Cates’ story. Some of the other students in the audience were inspired. They lobbied University of Kansas to rename a campus medical society for Dr. Cates; the group previously honored a dean of the school who had advocated for racially segregated clinical facilities.

Last year Dr. Manning attended the renaming ceremony for the Cates Society. “I was crying,” she said. “What I experienced is not on the spectrum of what my ancestors experienced at the hands of white physicians. But I spent five years at this institution thinking there was no hope.”

Watching the school publicly honor its first female Black graduate, she felt a glimmer of optimism: “I thought, maybe they do give a damn about the lives of Black students.”