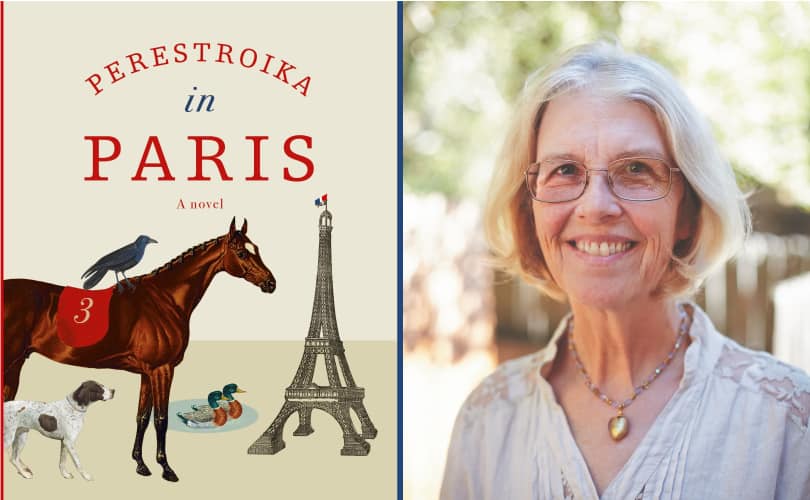

Perestroika in Paris, by Jane Smiley book review

[ad_1]

The interesting thing about all this — especially if you’re a book reviewer who’s never so much as ridden a horse — is that her fixation on horses demonstrates the breadth of Smiley’s skills, not her narrowness. Even when she’s writing about equine characters, Smiley, who won a Pulitzer in 1992 for “A Thousand Acres,” crafts intimate domestic stories and big-picture social novels, addresses kids and grown-ups, and writes in a host of registers. Her latest novel, the sprightly “Perestroika in Paris,” may be another horse novel, but here Smiley stretches her talents even further by entering another genre: the talking-animal book.

Perestroika — Paras for short — is a 3-year-old filly thoroughbred who’s just come off a win at a racetrack in Paris. Being a “very curious filly,” she trots away from her stable when she finds her stall door unlocked, then wanders to the Place du Trocadero near the Eiffel Tower. In short order, she’s joined by Frida, a canny German shorthaired pointer whose owner, a vagabond busker, has recently died; Raoul, a sage raven who keeps a perch on a Benjamin Franklin statue; and a pair of squabbling mallards, Sid and Nancy.

The world outside the racetrack is baffling to Paras, in terms of both its human and animal inhabitants. “What are you chasing?” Frida asks. “I don’t know,” she responds.

Talking-animal stories tend to break down into two categories: Sober allegories about human nature (“Animal Farm”) and lighter allegories via kids’ adventure tales (“Charlotte’s Web.”) But “Perestroika” doesn’t slot neatly into either group. Despite the title character’s name, the novel isn’t concerned with Cold War politics, or politics much at all. (The novel ends on a bright, decidedly un-Orwellian note: “Why make things more complicated than they really had to be?” ) And though the animals’ personalities tend to stick to the straightforward archetypes of children’s literature — daring, haughty, exploring, squawky — Smiley strives to avoid a cloying tale about getting along.

To help do that, she introduces a handful of more earthbound human characters, most prominently a nonagenarian matron, Madame de Mornay, and her 8-year-old orphan great-greatgrandson, Étienne, who live in a bespoke if declining manor. Étienne lures Paras to the home, where she makes the grand salon comfortable, if a bit smelly. The surrounding Parisians are oblivious — the novel would stop dead in its tracks if they weren’t. Smiley laments what they’re missing: “The humans who were out were, as usual, looking downward, minding their own business, thoroughly convinced that they knew all about everything having to do with their world.”

Paras’s animal pals are skeptical about her new arrangement. Raoul worries she’s been jailed, a word Frida needs to define for her: “You know, a small enclosed space where you can’t get in and out of your own accord, but must always bow and scrape and do tricks in order to achieve some sort of self-realization,” she explains. “A stall,” Paras deadpans. The assembled characters consider humanity from different angles, and their bemused observations are meant to suggest that people are just another kind of strange creature. “Dogs, evidently, saw humans as friends, whereas horses saw them as coworkers,” Paras observes to herself.

You get the idea. We self-centered humans are too often oblivious to the powerful, almost magical connection we have with animals. (A rat introduced late in the story has the ability to sense the diverse “broadcasts” of creatures’ personalities.) Meanwhile, the animals’ perspectives on people make our blessed strangeness easier to see. That makes Smiley’s fun, light read also something of a more serious literary challenge in characterization: Can a novelist give a novelist human traits, and vice versa, without teetering into unreality?

Though there’s a perhaps inevitable Disney-ish sheen to the proceedings, as if the novel was a high-end adaptation of a film like “Ratatouille.” Smiley has the comic sensibility to sustain the suspension of disbelief her setup demands. Raoul, she writes, “had seen flocks of mallards squawking constantly, as if shouting to humans, ‘Shoot me! I can’t stand myself any longer!’ ” And she knows when to cut the sugar, especially in the novel’s latter pages, as Étienne’s predicament becomes more complicated. But the boy and her great-grandmaman aside, most of the human characters are stock figures like the bumbling gendarme and the sweet-tempered shop owners who help keep Paras well-fed and out of police custody.

The trouble with trying to say something about humanity through animals is that it tends to make compassion toward animals humanity’s chief character trait — a sweet if not especially nuanced idea. It’s telling that the novel’s two main human characters are very young and very old — both immature enough to fit into this novel’s plot devices without seeming too absurd. That makes for a lighthearted spree of a novel, but there’s also a sense that it missed being something more than that, a story that spoke to common ground and human nature that’s true for a more universal audience. For, Smiley, a novelist who has long been open to trying new things, it’s a noble experiment. But as Raoul points out, “life is always a chancy business.”

Mark Athitakis is a critic in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Perestroika in Paris

[ad_2]

Source link