Returning students provide lessons for reopening schools

[ad_1]

Heather Powell breaks down how she balances a full time job and helping her kids with virtual learning.

Nashville Tennessean

NASHVILLE, Tenn. – Abigail Alexander shuffled through a stack of papers, trying to find instructions for logging in to her school-issued laptop.

The 10-year-old chatted with her best friend, a fellow fifth grader, about who is in their classes this year at Head Middle Magnet Prep and what period they have a specific teacher.

Their conversation Tuesday sounded like a typical one between excited, anxious students on the first day at a new school – except this year is like no other.

Abigail was seated in the dining room of her North Nashville home while her two younger foster siblings played around the table. Her friend was on FaceTime, the phone propped up against the side of Abigail’s laptop.

The girls are among more than 86,000 Nashville students who started the school year virtually while their schools remained closed during the the coronavirus outbreak.

Two states away in Indiana, where school districts opened with in-person instruction Wednesday, Health Commissioner Kris Box said cases in schools are inevitable, calling them a “reason for action,” not a cause for alarm. Box said outbreaks can be prevented and schools can reopen safely if they follow state recommendations and families screen for symptoms at home.

“The best way to prevent this is for everyone to do their part,” Box said, “and know when to stay home.”

While students and families cope with questions about how to keep themselves safe while they learn, reminders of the risk come at them from all directions: news of COVID-19 cases reported in schools that reopened, plus street marches and car caravans in dozens of school districts across the country protesting what activists called “unsafe” reopenings.

Abigail and her friend had their own concerns; both experienced access issues – to technology, school resources and the other services that schools offer millions of students across the country.

“I need help!” Abigail exclaimed as her laptop again failed to load or connect to the internet.

“Seriously,” her friend responded.

LaTonya Alexander tries to help her daughter Abigail, a fifth grader, set up for virtual learning at home on her first day of school Aug. 3 in Nashville. Abigail attends Head Middle Magnet School. (Photo: Alan Poizner for The Tennessean)

Setting the stage for the nation

Despite increasing COVID-19 cases across Tennessee, most of the state’s school districts reopen in person this month, and some of the suburban districts that surround Nashvilleand others in East Tennessee were among the first in the country to welcome back students after they closed in the spring.

These districts set the stage for others across the nation that will resume classes in the coming weeks. Nashville students’ success – or failure – at virtual learning will help inform what many districts face. Six of the nation’s seven largest school districts will open online.

Parents, educators, elected officials and doctors haven’t agreed on the best course of action for the country’s students.

The American Academy of Pediatrics initially recommended schools reopen, but as President Donald Trump pressured districts to do so, the group said public health agencies must make recommendations based on evidence. The group said reopening plans should start with the goal of getting students back in person, but in some communities, schools may have to start back virtually.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the nation’s leading expert on the coronavirus, told teachers during a virtual town hall last month they’d “be part of the experiment” of reopening schools.

That’s small comfort to many educators, students and their families. The Tennessee Education Association, teacher associations and others held mock funeral processions and “die-in” protests, arguing that teachers will quit. New York, Chicago and Milwaukee saw similar protests, and although many parents are reluctant to send their children back to school, they lament districts’ online learning plans.

At least 14 confirmed COVID-19 cases connected to schools have been reported in Tennessee, and two school districts closed schools or altered their schedules as a result of exposure to the virus. Cases have been reported at reopened schools in Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi and Georgia.

Even school districts that have yet to reopen have been affected. After Georgia’s Gwinnett County Public School teachers gathered July 29 for in-person planning, 260 employees were excluded from work the following day because of a positive case or contact with one.

For families and teachers worried about exposure, most districts offer some sort of remote learning option, but many parents said they need to send their children to school regardless of their fears.

Students across Tennessee are returning to school this week as many districts reopen. Not all students will return to the classroom though, some like Metro Nashville Public Schools students will learn virtually instead.

Nashville Tennessean

‘Hoping it goes well’

In Indianapolis, Taylor Fenoglio stood at the bus stop Wednesday morning, crying after watching her daughter Izzy get on the bus for her first day at Thompson Crossing Elementary School. Fenoglio already missed her.

Izzy? Not so much.

“She’s been dying for the interaction and was really excited,” Fenoglio said. “She pretty much ran onto the bus.”

A bus waits to take students home from Homecroft Elementary School in Indianapolis on the first day of classes Wednesday. (Photo: Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar)

That morning, Izzy posed for first-day-of-school pictures next to a chalkboard sign with a drawing of a face mask – something that’s quickly become a symbol of the 2020-21 school year. Though the state requires masks only for students in third grade and above, Franklin Township Schools requires them for all students (except for health reasons or other conditions).

The district offers a virtual option for families who aren’t ready to send kids back to school. Fenoglio said she and her husband discussed whether to go that route. But they have a new baby at home, and Fenoglio worried she wouldn’t be able to give her older daughter the support she needed for a successful start to kindergarten.

The unknowns of reopening schools in the midst of a pandemic made the stressful process of navigating school for the first time even more difficult, she said. But by the end of the first day, once her daughter was home, happy and exhausted, Fenoglio said she feels good about their choice.

“We are carefully optimistic about this year,” she said, “and just really hoping it goes well.”

Furthering divides

Many parents calling for schools to reopen worry about the quality of the remote instruction their children will receive.

Many districts called for more funding from state and local governments to provide technology and internet access to students, even as they face threatened funding cuts from the federal government if they don’t reopen.

Nashville students’ tech woes were limited to the students using district-issued devices Tuesday morning.

Some students and families were able to get online to join live classroom meetings or check in with their teachers on personal devices for the first day, but some of those dependent on devices provided by the district were left in the dark, exacerbating fears that gaps will widen between vulnerable students who come from economically disadvantaged families and more affluent peers.

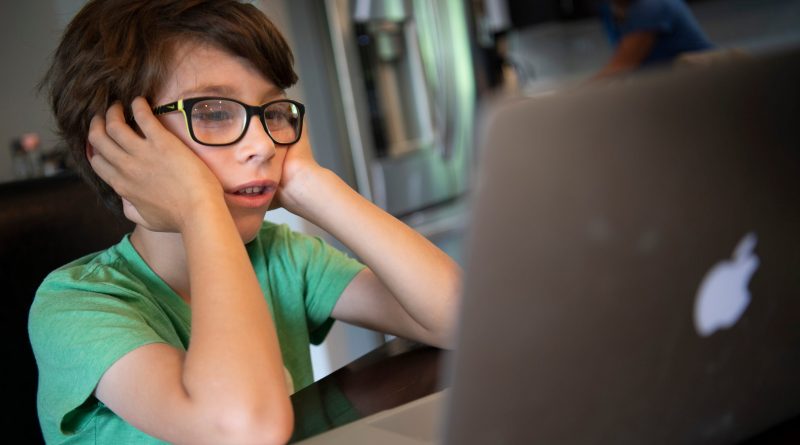

Heather Powell’s son, Hawkes, gives a thumbs up as they connect via a laptop and a group chat application to his first grade teacher at Glendale Elementary from their home on the first day of school Aug. 4 in Nashville. (Photo: George Walker IV / The Tennessean)

Heather Powell interrupted her workday to let her son, Hawkes, 6, use her work laptop to log in to a virtual meeting with his first grade class Tuesday morning.

The Powells tested both their children’s laptops the day before by logging on, but Tuesday morning, a Metro Nashville Public Schools network issue rendered the laptops useless for the time being.

“It already disrupted my workflow this morning,” Powell said. “It worked today, but it won’t work for the long term.”

Powell’s daughter, Sophie, 9, was at a friend’s house as part of a learning pod, but only one child had a personal device she could use to log in.

Struggling to balance working full-time at home, keeping both her children engaged and meeting their social-emotional needs, Powell tracked down learning pods – in-person microschools.

In learning pods, parents band together with neighbors to link up classmates from the same school or grade level and hire private tutors or teachers.

Costs vary, and some schools help families connect. In some cities, families dole out hundreds of dollars to pay for private instruction or send their children to “virtual learning camps.”

Some families pull children out of the public school system to send them to private schools reopening in person, or they home-school with their own curriculum.

Both of the Powell children’s pods will stick to Metro Nashville Schools’ curriculum. The students will rotate houses each week, Powell explained. She hopes the tutor will relieve the burden on parents, so she can concentrate on work while the kids learn.

After the frantic morning of the first day, Powell called it quits and took the second half of the day off. She and Hawkes went to the pool.

“I think that’s what we need today,” she said.

First grader Hawkes Powell pays attention to a lesson from his class on a laptop Aug. 4 in Nashville. (Photo: George Walker IV / The Tennessean)

When families don’t have options

Abigail’s mother, LaTonya Alexander, isn’t sure what she would have chosen for her children if she’d had a choice.

She and her husband had to shift their work schedules, so someone is at home with her three children and two foster children, ranging from kindergarten to 12th grade.

Alexander’s daughter, Anaya, is a senior in high school. Her son, Wilton, is starting the 10th grade. Both would prefer to be at school, Alexander said.

She has more confidence that older children will take health and safety precautions seriously, wearing masks, washing their hands and social distancing. Remote learning is more difficult for younger students.

Alexander is a hairstylist and her husband a barber, so exposure is a concern. As a Black family, they are among an American population getting infected and dying at disproportionately higher rates than white people.

LaTonya Alexander, center, gets virtual learning on the first day of school with her tenth grade son, Wilton, and fifth grade daughter, Abigail, at their home Aug. 4. Wilton attends Maplewood High School, and Abigail attends Head Middle Magnet School. (Photo: Alan Poizner)

The Alexanders are dependent on laptops distributed by Metro Nashville Public Schools. With five kids in the house, there isn’t enough work space – much less technology – to go around.

The family picked up four laptops, among more than 34,000 that the district has distributed to students, a day before the first day of school.

The youngest, a kindergartner, doesn’t have a device. “I wish I could meet my teacher,” she said Tuesday morning.

Instead, she sat quietly next to Abigail at the family’s dining room table, snacking on grapes and watching the other children try to log on to their computers.

Contributing: Kelly Fisher

Read or Share this story: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2020/08/06/covid-19-returning-students-provide-lessons-reopening-schools/3304403001/