S. Clay Wilson, who helped launch the underground comix movement, dies at 79

[ad_1]

The cause was complications from a traumatic brain injury, said his wife, Lorraine Chamberlain. Mr. Wilson spent a year in the hospital after being found face down and unconscious between two parked cars in 2008. He had been walking home drunk from a friend’s house in San Francisco, his wife said, and he suffered seizures and aphasia before being hospitalized in 2019 for a ruptured esophagus.

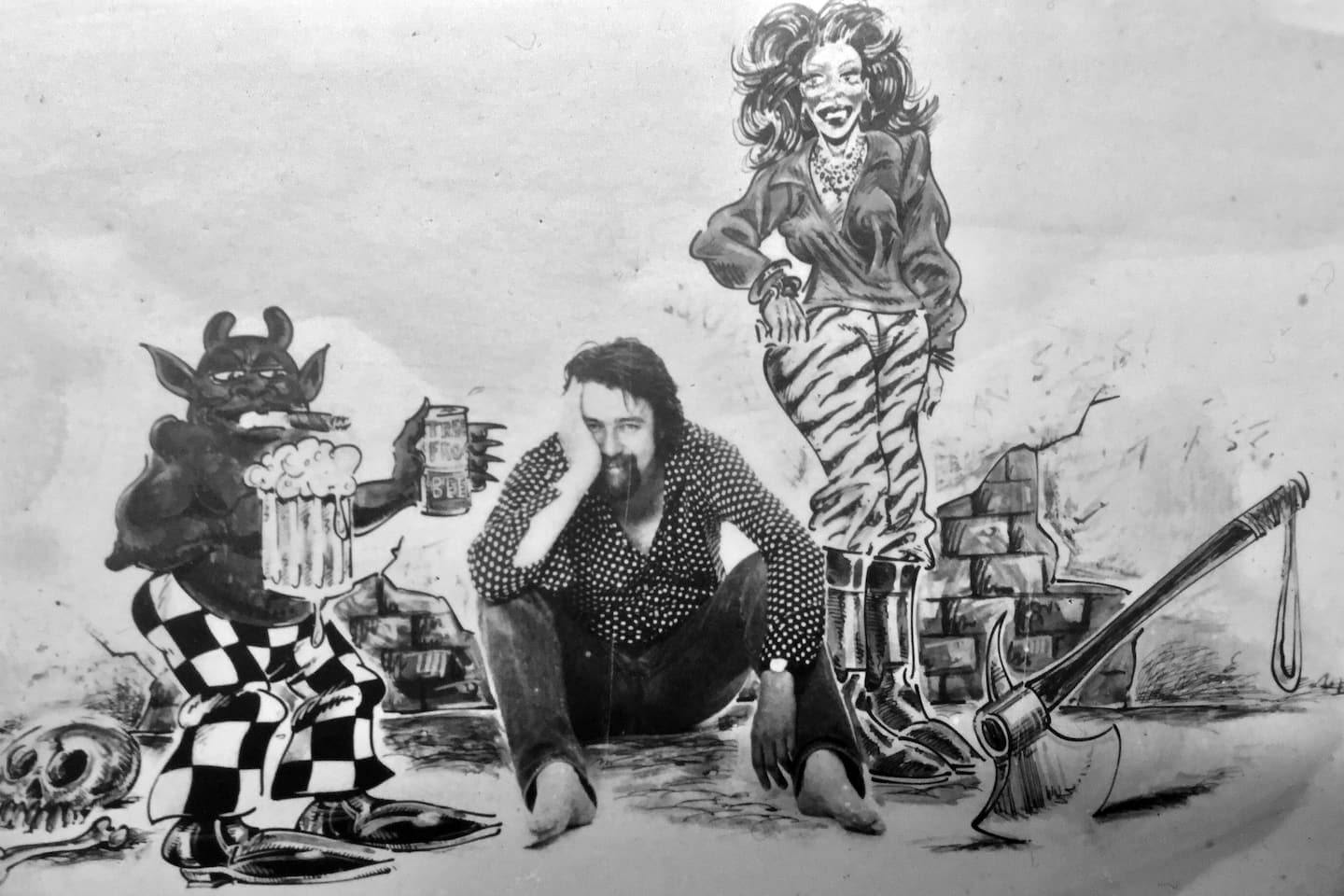

Mr. Wilson populated his work with a deranged cast of demons, lowlifes, barkeepers, ghouls, drunks, bikers, prostitutes and — though he grew up in Nebraska — pirates, drawing richly detailed panels that drew comparisons to the nightmarish paintings of Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch.

Although he was often overshadowed by Crumb — the creator of “Keep on Truckin’,” Fritz the Cat and the bearded mystic Mr. Natural — Mr. Wilson was widely credited with paving the way for the underground comix movement of the 1960s and ’70s. The Comics Code Authority had regulated comics sold in drugstores and newsstands, but Mr. Wilson effectively grabbed hold of their rule book, ran it through a shredder and set the scraps on fire, shocking even Crumb.

“The content was something like I’d never seen before, anywhere, the level of mayhem, violence, dismemberment, naked women, loose body parts, huge, obscene sex organs, a nightmare vision of hell-on-earth never so graphically illustrated before in the history of art,” Crumb later recalled, describing his first exposure to Mr. Wilson’s work in 1968. “After the breakthrough that Wilson had somehow made, I no longer saw any reason to hold back my own depraved id in my work.”

Mr. Wilson published his cartoons in a host of underground magazines, tabloids and anthologies, including Bill Griffith and Art Spiegelman’s Arcade, Kim Deitch’s Gothic Blimp Works and Crumb’s Weirdo. But he was most closely associated with Zap, which began in San Francisco in early 1968 as a showcase for Crumb. Later that year, it expanded to include work by Mr. Wilson, Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso. The cover of its second issue promised “gags, jokes, kozmic trooths,” at a cost of only 50 cents.

“I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to go to hell for reading this,’ ” cartoonist Gilbert Hernandez told the New York Times in 2014, when Fantagraphics published a 1,100-page collection of all 16 issues of Zap. “The Zap artists, they’re like these crazy children. The naughtiest kids in the world.”

Distributed at head shops and under the counter at comic stores, Zap came out in the midst of the 1960s counterculture, with anti-Vietnam War protests raging, LSD use on the rise and the film industry shedding its own long-standing production code. The magazine’s comics sparked censorship battles, crackdowns at bookstores and public outrage, not least over Mr. Wilson’s cartoon “Head First,” a one-page flurry of sex, dismemberment and cannibalism that featured his Pervert Pirates characters.

“He showed us we had been censoring ourselves,” Moscoso later told the Times. “He blew the doors off the church. Wilson is one of the major artists of our generation.”

Mr. Wilson collaborated with writers, artists and musicians such as William S. Burroughs, Terry Southern, Kathy Acker and Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders, and was credited with shaping the beat and punk movements, as well as biker and tattoo cultures.

In recent years, he and some of his raunchier peers were accused of sexism and misogyny, criticized by younger generations of cartoonists and critics who asked why they needed to draw women who were mutilated or raped.

Mr. Wilson insisted he never felt a need to dial things back.

“I’m doing these things because I like drawing dirty pictures,” he once said, according to Patrick Rosenkranz’s 2014 biography “Pirates in the Heartland: The Mythology of S. Clay Wilson.” “It’s enjoyable because it’s dirty. It’s the idea of breaking a taboo. Probably even as little as five years from now a lot of this stuff will either look fairly bland or be accepted.”

“I have this morbid fascination with deviancy, and I like drawing it in comic strips,” he added. “I find it entertaining. I’m sure a shrink would have a field day trying to figure out why I did it. People can take it or leave it.”

Steven Clay Wilson was born in Lincoln, Neb., on July 25, 1941. His father was a master machinist — “he could make anything, including silencers and fuel pumps for Offenhausers,” Mr. Wilson said — and his mother was a stenographer at a psychiatric hospital. An uncle ran a drugstore and brought him unsold issues of EC Comics, fueling Mr. Wilson’s early desire to be a cartoonist.

“I remember as a kid seeing the first television in my neighborhood,” he told cartoonist Spain Rodriguez in 2005, for an interview in Juxtapoz magazine. “I asked Ma, ‘When are we going to get a TV?’ She looked at me and threw a pencil at me. She said, ‘Draw your own pictures.’ ”

Mr. Wilson studied art and anthropology at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, served in the Army and moved to Lawrence, Kan., where he published some of his first drawings in the poetry magazine Grist. He settled in San Francisco in 1968, befriended Crumb and soon began contributing to Zap.

The magazine’s second issue featured the Checkered Demon, Mr. Wilson’s best-known character, a portly devil with a gaptoothed smile that evoked the Mad magazine mascot Alfred E. Neuman. Mr. Wilson was said to have created the character after watching “Juliet of the Spirits,” a dreamlike 1965 movie directed by Federico Fellini, while on LSD.

The demon remained a staple of his work for decades, battling bad guys and cavorting with characters such as Star-Eyed Stella. Mr. Wilson also turned to more family-friendly material in the 1990s, providing the illustrations for fairy tales written by Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm.

In 2010 he married Chamberlain, his on-again-off-again girlfriend of more than four decades, and an artist who was previously married to sculptor John Chamberlain. After his brain injury, he slowly lost the ability to draw and turned into a “kinder, gentler S. Clay Wilson,” as she once put it. He had long been known for his rapid-fire conversation and heavy drinking, with a neighborhood watering hole, Dicks, serving as his office in San Francisco.

In addition to his wife, survivors include a sister.

“I think a comic strip, like jazz, is pretty American,” Mr. Wilson once said. “The variations of how much stuff you can cram into a comic strip or how far you can stretch the envelope in a form of music or a comic strip is pretty endless, you’re limited only by your imagination. You get aesthetic debates and nuances of details. … But just draw [it] and argue later.”