Sargeant Salonger, by Jerome Charyn book review

[ad_1]

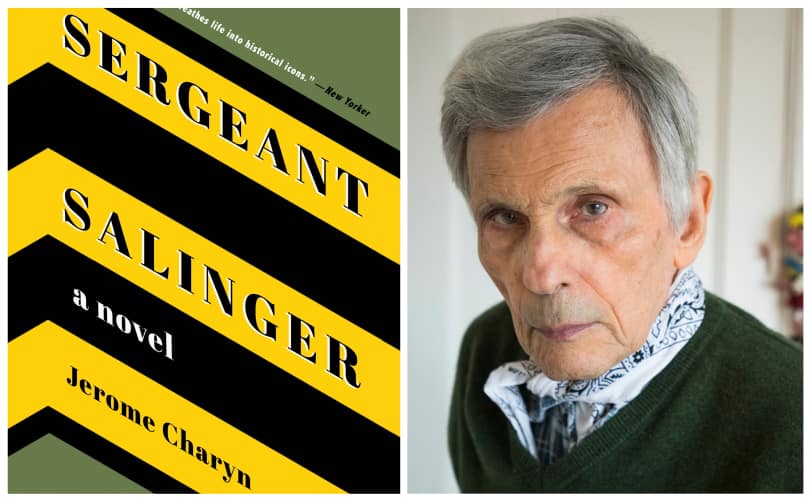

“Sergeant Salinger,” Jerome Charyn’s novel about the author’s adventures during World War II, is our consolation prize.

Charyn, who at 83 has had a remarkably prolific career, has an affinity for literary sphinxes. His 2010 novel, “The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson,” imagined the poet as furtive and lust-struck. In 2017’s “Jerzy,” he considered the novelist Jerzy Kosinki’s oddball demeanor and inexplicable suicide. Here, Charyn isn’t trying to sort out Salinger’s decision to go into hiding after the meteoric success of “The Catcher in the Rye.” The pressing question is what sparked his literary career in the first place.

Short answer: Phonies. Drawn from Salinger’s actual experiences in love and war, the novel opens in 1942, as Salinger is just launching his career. He has a girlfriend — Eugene O’Neill’s daughter, Oona — but she’s a popular debutante slipping out of his grasp. (She would later marry Charlie Chaplin.) He’s the scion of a well-off Manhattan family but tired of its strictures. At the Stork Club, columnist Walter Winchell is impressed enough with him to offer a writing job, but Salinger wants none of his braggadocio or his jibes against his idol, Ernest Hemingway, who’s sitting right beside him.

Once Salinger, a.k.a. Sonny, is drafted into the Army, all that petty social-set striving gets shunted aside. Salinger served in the Counterintelligence Corps and saw some of the European theater’s fiercest fighting at Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge. Charyn unflinchingly relates war’s parade of grotesqueries: German bombs on the beach set off “a minor hurricane, dogfaces flying into the air like rag dolls, every sort of paraphernalia struck the water — helmets, Hershey bars, and human limbs.”

But for all the physical carnage Sonny witnesses, Charyn suggests the author is equally affected by the duplicity and fakeness of those around him. Charged with interrogating prisoners of war, he grows used to deceit. The phoniness extends up through the chain of command, the stragglers of Vichy France, and — worst of all — his literary hero. In Paris, he’s charged with confronting Hemingway, who has assembled a band of resistance fighters but mainly seems to be a Falstaffian self-parody, playacting at past glories.

In a sentence, Charyn passes the literary torch: “War had become a kind of romance to Papa, a quixotic quest, with bandoliers and invented fables and flags, while it was nothing but pillage to Sonny, the soiling of a landscape, all the unheroic horror and static silences that Hem himself had once written about.”

Salinger’s disillusionment reaches its climax in 1945, as he helps liberate one of the camps at Dachau, in a masterful and stomach-churning set piece. He checks himself into an asylum, where he meets Sylvia, who would be his first wife, and braces for a lifetime of consumption with injustice, starting with denazification: “Some local schoolteacher was put in a cage, while rocket scientists and aeronautical engineers were treated like little kings and chauffeured to America on heavy bombers converted into transport planes.”

In outline, “Sergeant Salinger” is true to history. But it also strains to connect the author with his literary creations. Charyn steers Sonny to be an echo of the men in two of Salinger’s classic stories about soldiers, “For Esmé — With Love and Squalor” and “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” (Salinger’s sister feels that “Sonny’s homecoming . . . was a subtle form of suicide,” echoing the death at the end of the latter story.) In an essay on Salinger published in 2019 by Forward, Charyn described Salinger as “the author of frozen adolescence, one more lost bar mitzvah boy in search of a manhood that will never come.” In the novel, Charyn leaves his melancholy Salinger unfinished in a similar way. By the novel’s end, Sonny is weathered by war but remains unprepared to write the fiction that would make his career: “Sonny wanted to write sentences that would scorch the reader’s soul like shards of burning ice. But he was impotent, even in his Eisenhower.”

How he’ll surpass that impotence isn’t clear, and the blankness grates a little — shouldn’t a historical fiction provide a fuller picture of a person, one that the historical record can’t provide? Charyn’s Salinger is an empty vessel, collecting ennui and experiences, despairing for some way to clarify it all in fiction. He would get there, somehow. But in this novel, as with much of Salinger’s life, we have to accept a certain amount of mystery.

Mark Athitakis is a critic in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Sergeant Salinger

Bellevue Literary Press. 288 pp. $28.99

[ad_2]

Source link