The action-packed saga ‘Monkey King: Journey to the West’ gets a modern take

[ad_1]

Today, “Journey to the West” is said to be the most popular book in East Asia, as well as a seed-text for children’s stories, films, anime and comics. Appropriately, then, Lovell’s translation carries a foreword by Gene Luen Yang, MacArthur-Award-winning author of the graphic novel “American Born Chinese,” which draws on this rumbustious fantasy.

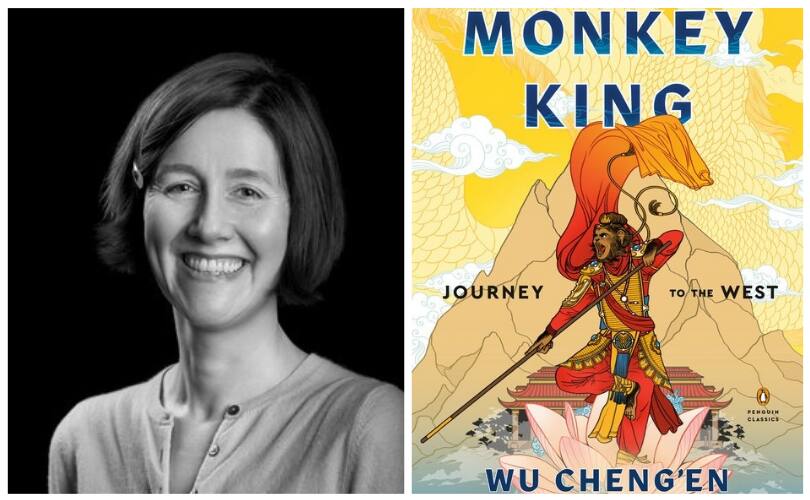

The marvel-filled narrative — 100 chapters in the original — derives from popular tales and dramas about a shape-changing trickster and proto-superhero who happens to be a talking monkey. Its other characters, as Lovell — professor of Chinese at the University of London — notes in her excellent introduction, include “gods, demons, emperors, bureaucrats, monks, animals, woodcutters, bandits and farmers” — in short a cross-section of Ming-era imperial China.

The opening chapters depict the mysterious birth of Monkey, his early religious training under a Taoist Immortal, his acquisition of a supernatural fighting staff, and the trouble this simian upstart causes when, in his quest for the secret to eternal life, he disrupts the celestial court-in-the-clouds of the Jade Emperor. There he offends virtually everyone, devouring the Jade Empress’s life-extending peaches and drinking the immortality elixirs of Laozi, the Taoist patriarch. Exiled back to Earth, Monkey and his armies battle the forces of Heaven successfully until the Buddha finally imprisons him under a mountain. His adventures, however, are just beginning.

All these initial chapters of “Monkey King” exhibit a rollicking exuberance, somewhat like Rabelais’s hyperbolic accounts of the giants Gargantua and Pantagruel. Monkey consistently acts with crude outrageousness — at one point he actually urinates on the Buddha’s hand. Because the novel’s Chinese vernacular is both vulgar and linguistically playful, Lovell’s translation adopts a snappy contemporary vibe. Heaven, we learn, “runs a cashless economy.” The welcome sign outside the Underworld reads, “The Capital of Darkness: A Fine City.” A hermit, asked how he’s doing, answers, “Oh, same old, same old.” Some of Lovell’s descriptive epithets even recall the comic sententiousness of Ernest Bramah’s tall tales about the resourceful Kai Lung. The Pillar of Ultimate Peace, for instance, refers to the execution block.

After 500 years pass, Monkey is offered release from his imprisonment if he will become the disciple and bodyguard of a Buddhist monk undertaking an arduous mission to India. Tripitaka, as the monk is nicknamed, has been tasked by China’s emperor to bring back special sutras of salvation from Thunderclap Monastery on Soul Mountain. A whiny, somewhat dimwitted holy man, Tripitaka needs all the help he can get. His entourage ultimately comprises a dragon that can assume the shape of a horse, a former Immortal named Pigsy who “took a wrong turn on the path to Karma and ended up being reborn as a hog,” an ex-cannibal called Sandy and, most important of all, the clever and invincible Monkey.

Admittedly, all this sounds pretty entertaining, rather like a kung fu or superhero film. Monkey and Pigsy even exchange the de rigueur banter and mutual putdowns of such action movies. Unfortunately, there’s just no real suspense to the various challenges facing our heroes. Typically, some monster or demon spies the travelers and decides to eat them. To do this, it transforms itself into an old peasant, a fellow Buddhist or a beautiful young woman. Invariably, all the pilgrims are taken in by this subterfuge, except Monkey, who saves the day with his own shape-changing magic, then finishes off the fiend by smashing its skull with his trusty iron staff.

Over time, Monkey does gain some empathy and a moral sense, most notably when he rescues 1,111 little boys from being sacrificed to a deluded king. Our heroes even learn a little about what life is like for the opposite sex: When passing through the Land of Women, Tripitaka and Pigsy accidentally drink a special water that induces pregnancy. In the end, this ragtag band finally acquires the sutra scrolls from a surprisingly worldly-wise Buddha and achieves a kind of sainthood for themselves.

Still, I wanted to like the book more. Even abridged to a quarter of the original, its long central section struck me as repetitive, tedious and cartoonishly crude. Overall, “Monkey King” lacked the charm of Western fairy tales, medieval chivalric romances or “The Arabian Nights,” each of which it occasionally resembles. Neither was there any of the wondrous eeriness or erotic poignancy of Pu Songling’s slightly later classic, “Strange Stories From a Chinese Studio.”

Being unhappy with these lukewarm feelings, I decided that some extra research might give me a deeper appreciation of this widely acknowledged masterpiece.

As usual, I got caught up in that research, consulting reference books, reading the introductions and afterwords to earlier translations (by Arthur Waley, W.J.F. Jenner and Anthony Yu), and learning about the historicity of Tripitaka and the varying interpretations of this folk epic. Some critics, I discovered, view this classic as just slapstick entertainment about a mischievous monkey, others see it as a satirical critique of 16th-century China and still others regard it as a religious allegory, perhaps a plea for the essential unity behind Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. In Maoist times, Monkey has even been proclaimed a Marxist revolutionary, intent on overturning the oppressive imperial order.

Clearly, “Monkey King: Journey to the West” has long been — and will continue to be — a rewarding and enjoyable reading experience for many people. It’s my loss that I’m not among them. Still, I remain all the more eager to try several other monuments of Chinese fiction, starting with Cao Xueqin’s five-volume novel of manners, “The Story of the Stone.”

Michael Dirda reviews books for Style every Thursday.

Monkey King: Journey to the West

By Wu Cheng’en. Translated and edited by Julia Lovell.

Penguin Classics. 384 pp. $30

[ad_2]

Source link