The Mystery of the Disappearing van Gogh

[ad_1]

The bidding for Lot 17 started at $23 million.

In the packed room at Sotheby’s in Manhattan, the price quickly climbed: $32 million, $42 million, $48 million. Then a new prospective buyer, calling from China, made it a contest between just two people.

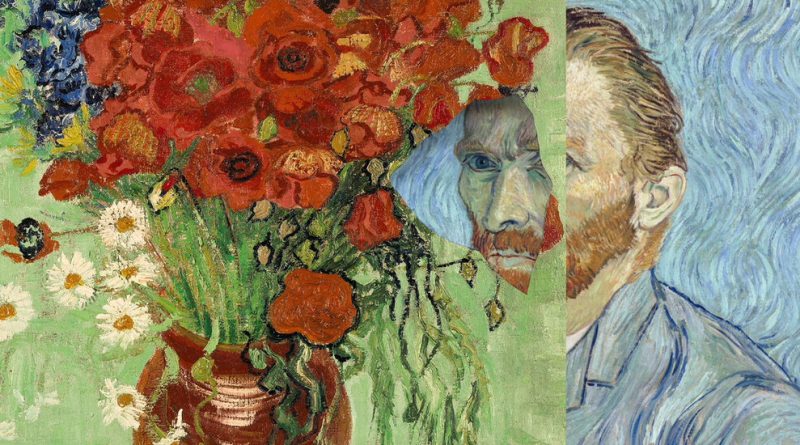

On the block that evening in November 2014 were works by Impressionist painters and Modernist sculptors that would make the auction the most successful yet in the firm’s history. But one painting drew particular attention: “Still Life, Vase with Daisies and Poppies,” completed by Vincent van Gogh weeks before his death.

Pushing the price to almost $62 million, the Chinese caller prevailed. His offer was the highest ever for a van Gogh still life at auction.

In the discreet world of high-end art, buyers often remain anonymous. But the winning bidder, a prominent movie producer, would proclaim in interview after interview that he was the painting’s new owner.

The producer, Wang Zhongjun, was on a roll. His company had just helped bring “Fury,” the World War II movie starring Brad Pitt, to cinemas. He dreamed of making his business China’s version of the Walt Disney Company.

The sale, according to Chinese media, became a national “sensation.” It was a sign — after the acquisition of a Picasso by a Chinese real estate tycoon the year before — that the country was becoming a force in the global art market.

“Ten years ago, I could not have imagined purchasing a van Gogh,” Mr. Wang said in a Chinese-language interview with Sotheby’s. “After buying it, I loved it so much.”

But Mr. Wang may not be the real owner at all. Two other men were linked to the purchase: an obscure middleman in Shanghai who paid Sotheby’s bill through a Caribbean shell company, and the person he answered to — a reclusive billionaire in Hong Kong.

The billionaire, Xiao Jianhua, was one of the most influential tycoons of China’s gilded age, creating a financial empire in recent decades by exploiting ties to the Communist Party elite and a new class of superrich businessmen. He also controlled a hidden offshore network of more than 130 companies holding over $5 billion in assets, according to corporate documents obtained by The New York Times. Among them was Sotheby’s invoice for the van Gogh.

The secrecy that pervades the art world and its dealmakers — including international auction houses like Sotheby’s — has drawn scrutiny in the years since the sale as authorities try to combat criminal activity. Large transactions often pass through murky intermediaries, and the vetting of them is opaque. Citing client confidentiality, Sotheby’s declined to comment on the purchase.

Today, Mr. Xiao is a man who has fallen far. Abducted from his luxury apartment and now imprisoned in mainland China, he was convicted of bribery and other misdeeds that prosecutors claimed had threatened the country’s financial security. Meanwhile, Mr. Wang is struggling, liquidating properties as his film studio loses money each year.

And the still life, according to several art experts, has been offered for private sale. For a century after van Gogh gathered flowers and placed them in an earthen vase to paint, the artwork’s provenance could be easily traced, and the piece was often exhibited in museums for visitors to admire. Now the painting has vanished from public view, its whereabouts unknown.

A Painting’s Many Lives

In May 1890, van Gogh arrived in Auvers-sur-Oise, a rustic village outside Paris. Deeply depressed, he had cut off much of his left ear a year and a half earlier. His stay at an asylum had not helped.

But within hours of coming to the village, he met Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, a doctor and an art enthusiast.

“I’ve found in Dr. Gachet a ready-made friend and something like a new brother,” van Gogh wrote to his sister.

The physician encouraged van Gogh to ignore his melancholy and focus on his paintings. He completed nearly 80 of them in two months, including “Portrait of Dr. Gachet,” considered a masterpiece. He produced “Vase With Daisies and Poppies” at the physician’s home and may have given it to him in exchange for treatment, biographers say.

After van Gogh’s death in July 1890, the painting passed to a Parisian collector, and then, in 1911, as the artist’s fame was rising, to a Berlin art dealer. A series of German collectors owned it before A. Conger Goodyear, a Buffalo industrialist and a founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, bought it in 1928. His son George later granted partial ownership to Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery, which displayed it for nearly three decades.

In May 1990, capping years of record-breaking prices for van Goghs, a Japanese businessman spent $82.5 million for “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” at Christie’s, then the highest price paid at auction for any artwork.

About that time, Mr. Goodyear wanted to sell the 26-by-20-inch still life to raise money for another museum. It failed to sell at Christie’s in November 1990, where it had been expected to fetch between $12 million and $16 million. Soon after, a lower offer was accepted from a buyer who remained anonymous.

Most of the 400 or so oil paintings van Gogh produced during his last years — considered his best work — are at arts institutions around the world. About 15 percent are in private hands and not regularly on loan to museums. In the past decade, just 16 have been offered at auction, according to Artnet, an industry database. Among them was “Orchard With Cypresses,” from the collection of the Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, which Christie’s sold last year for $117 million to an undisclosed buyer.

The Producer and the Billionaire

For a year after the November 2014 auction, Mr. Wang kept the still life at his $25 million apartment in Hong Kong. In October 2015, the film producer was the guest of honor at a five-day exhibition in the city. An amateur artist, he had more than a dozen of his own oil paintings on display.

But the main attractions were the van Gogh and a Picasso he had recently bought, “Woman With a Hairbun on a Sofa.” Sotheby’s said Mr. Wang had paid nearly $30 million for the work.

Until then, Japanese industrialists, followed by American hedge fund managers and Russian oligarchs, had captured headlines for record-breaking purchases. Around 2012, newly rich Chinese buyers, who had benefited from their country’s market-opening policies, came on the scene.

“All the auction houses really jumped on that,” said David Norman, who headed Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern art department when the van Gogh was sold.

Chinese billionaires were often delighted to announce their big-ticket purchases. In 2013, a retail magnate bought a Picasso for $28 million at Christie’s, following up with a $20 million Monet at Sotheby’s in 2015. The same year, a stock investor spent $170 million at Christie’s for a Modigliani.

“It is a combination of vanity, investment and building their own brand,” said Kejia Wu, who taught at Sotheby’s Institute of Art and is the author of a new book on China’s art market.

Mr. Wang, 63, basked in the spotlight. In interviews, he spoke of his admiration for van Gogh and the artist’s influence on him. “Few people in the world would buy this kind of painting — there aren’t that many who love Impressionist art this much and can afford it, right?”

Days after the hammer fell at Sotheby’s, Mr. Wang had told a Chinese publication that he had not bought the painting alone, though he offered no details. Later, he no longer mentioned any partner. “When I saw the painting at a preview, I just felt like owning it — it stirred my heart,” he said in an interview published on Sotheby’s website.

The high-profile acquisition, made through an intermediary and with the ultimate source of funds remaining a secret, is the kind of transaction governments have been trying to curb in recent years.

In one scandal, the United States charged a Malaysian businessman with laundering billions of dollars from a state development fund, using some of it to buy art at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. In 2020, the Senate issued a scathing report on how auction houses and art dealers had unwittingly helped Russians evade sanctions by allowing others to buy art for them.

A spokeswoman for Sotheby’s said it vetted all buyers and, when necessary, enlisted its compliance department for “enhanced due diligence.” Sotheby’s applies worldwide a 2020 European Union rule that requires auction houses to verify the legitimacy of funds.

While the financial documents involving the van Gogh do not show wrongdoing, the transaction was hardly routine. Soon after the auction, Sotheby’s transferred ownership of the painting to the Shanghai man, neither a known art agent nor a collector, who paid the bill. But in a public ceremony, Sotheby’s handed over the painting not to him or the billionaire who employed him but to the producer, Mr. Wang.

“There’s a connection to someone who is now incarcerated,” said Leila Amineddoleh, a New York-based art lawyer. “Something unusual is going on.”

‘White Gloves’

The man Sotheby’s considers the owner of the van Gogh lives in a Shanghai apartment complex where gray tiles and grimy grout frame a weather-beaten door. A mat out front states nine times, in English, “I am an artist.”

The occupant, Liu Hailong, is listed as the sole owner and lone director of the shell company in the British Virgin Islands that paid for the painting: Islandwide Holdings Limited. Other than his date and place of birth, little is known about Mr. Liu, 46.

When a reporter recently showed him the Sotheby’s invoice and a bank wire document and asked whether the signature was his, he said, “Please leave immediately,” and shut the door.

A woman living with him, Zhao Tingting, has her own connection to the jailed billionaire, Mr. Xiao. She was once a top official at a company he co-founded, which had business dealings with relatives of China’s top leader, Xi Jinping.

Ms. Zhao, 43, who no longer holds that position, now teaches piano. Asked about Mr. Liu’s purchase of the van Gogh, she responded, “Do you think our house comes close to the price of that painting?”

She and Mr. Liu were “just ordinary little employees,” she said, with no connection to the Tomorrow Group, the collection of companies controlled by the billionaire. “We have no right to make any decisions and no right to know anything.”

The couple appear to have been “white gloves,” a term used in China to describe proxy shareholders meant to hide companies’ true owners. Among the thousands of pages of records providing details about the Tomorrow Group is a spreadsheet listing dozens of such people. At least four offshore companies were registered in Mr. Liu’s name.

Those companies were part of Mr. Xiao’s vast enterprise. He had showed early promise, gaining admission to China’s prestigious Peking University at age 14 and serving as a student leader during the 1989 Tiananmen protests. He sided with the government, an allegiance that would help him become one of the country’s richest men, acquiring control of banks, insurers and brokerages, as well as stakes in coal, cement and real estate.

Unlike the many brash billionaires he did business with, Mr. Xiao, now 51, preferred to operate in the shadows, building ties to some of China’s princelings. He settled into a quiet life at the Four Seasons, where a coterie of female bodyguards attended to his needs.

Why one of his lieutenants paid for the van Gogh is not clear. Mr. Wang, the producer, was among the ranks of China’s wealthiest people, though not nearly as rich as Mr. Xiao.

Mr. Xiao’s easy access to money outside China through his offshore network allowed him to bypass the country’s strict currency controls; he may have acted as a kind of banker for Mr. Wang. The documents show that the two men were drawing up art investment plans the same month as the auction, but their joint venture, based in the Seychelles, wasn’t formed until a year later. Meanwhile, the two set up another offshore company, aimed at investing in film and television projects in North America.

There could be another explanation for the payment: Mr. Xiao may have wanted to acquire an asset that could be transported across borders in a private jet, free from scrutiny by bank compliance officers and government regulators.

An Abduction, and a Vanishing Act

The fortunes of the men connected to the van Gogh purchase began to turn in 2015 with the crash of the Chinese stock market. Mr. Xi’s government blamed market manipulation by well-connected traders, and regulators wrested economic power back from the billionaires. Dozens of financiers disappeared, only to resurface in police custody.

Art purchases became more discreet. In 2016, Oprah Winfrey sold a Klimt painting to an anonymous Chinese buyer for $150 million.

By early 2017, Mr. Xiao’s life as a free man was over. One night, about a half-dozen men put him in a wheelchair — he was not known to use one — covered his face and removed him from his Hong Kong apartment. He was taken to mainland China and eventually charged. Prosecutors claimed that his crimes dated back before 2014, the year the van Gogh was sold.

He was sentenced last August to 13 years in prison for manipulating financial markets and bribing state officials. The court said Mr. Xiao and his company had misused more than $20 billion.

Government officials dismantled his companies in China. At some point, the British Virgin Islands business that bought the van Gogh changed hands and Mr. Liu was removed as its owner.

For a while, Mr. Wang, the producer, maintained a high-flying lifestyle, opening a private museum in Beijing in 2017 that showcased the van Gogh and Picasso paintings for a few months.

But the market value of his film studio, Huayi Brothers, vaporized as it backed flops. Mr. Wang let go much of his art collection and his Hong Kong home. Last year the Beijing museum was sold off, along with a mansion tied to him in Beverly Hills.

Mr. Wang and a spokesman for his company did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Mr. Xiao could not be reached for comment in prison, though a family representative said the billionaire’s wife did not know of any involvement in the van Gogh purchase and was unfamiliar with Mr. Liu.

Van Gogh’s floral still life — a vibrant painting by one of the world’s most acclaimed artists — hasn’t been seen publicly for years. But there are reports that the artwork may be back on the market.

Three people, including two former Sotheby’s executives and a New York art adviser, requesting anonymity, said the painting had been offered for private sale. Last year, the adviser viewed a written proposal to buy it for about $70 million.

The art experts did not know whether the painting had sold or if concerns had been raised about the 2014 sale — a purchase by a onetime lieutenant to a now disgraced billionaire linked to a beleaguered film producer who claims the art belongs to him.

“Nobody needs a $62 million van Gogh, and nobody wants to buy a lawsuit,” said Thomas C. Danziger, an art lawyer. “If there’s any question about the painting’s ownership, people will buy a different artwork — or another airplane.”

Graham Bowley contributed reporting. Susan C. Beachy and Julie Tate contributed research.

Produced by Rumsey Taylor. Photo editing by Stephen Reiss. Top images: “Still Life, Vase with Daisies and Poppies”: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images; Vincent Van Gogh: Imagno/Getty Images; Paul Cassirer: ullstein bild via Getty Images; Albright-Knox Art Gallery: Tom Ridout/Alamy; Sotheby’s auction: YouTube.

[ad_2]

Shared From Source link Arts