‘The Perfect Nine’ by Nigugi wa Thiong’o book review

[ad_1]

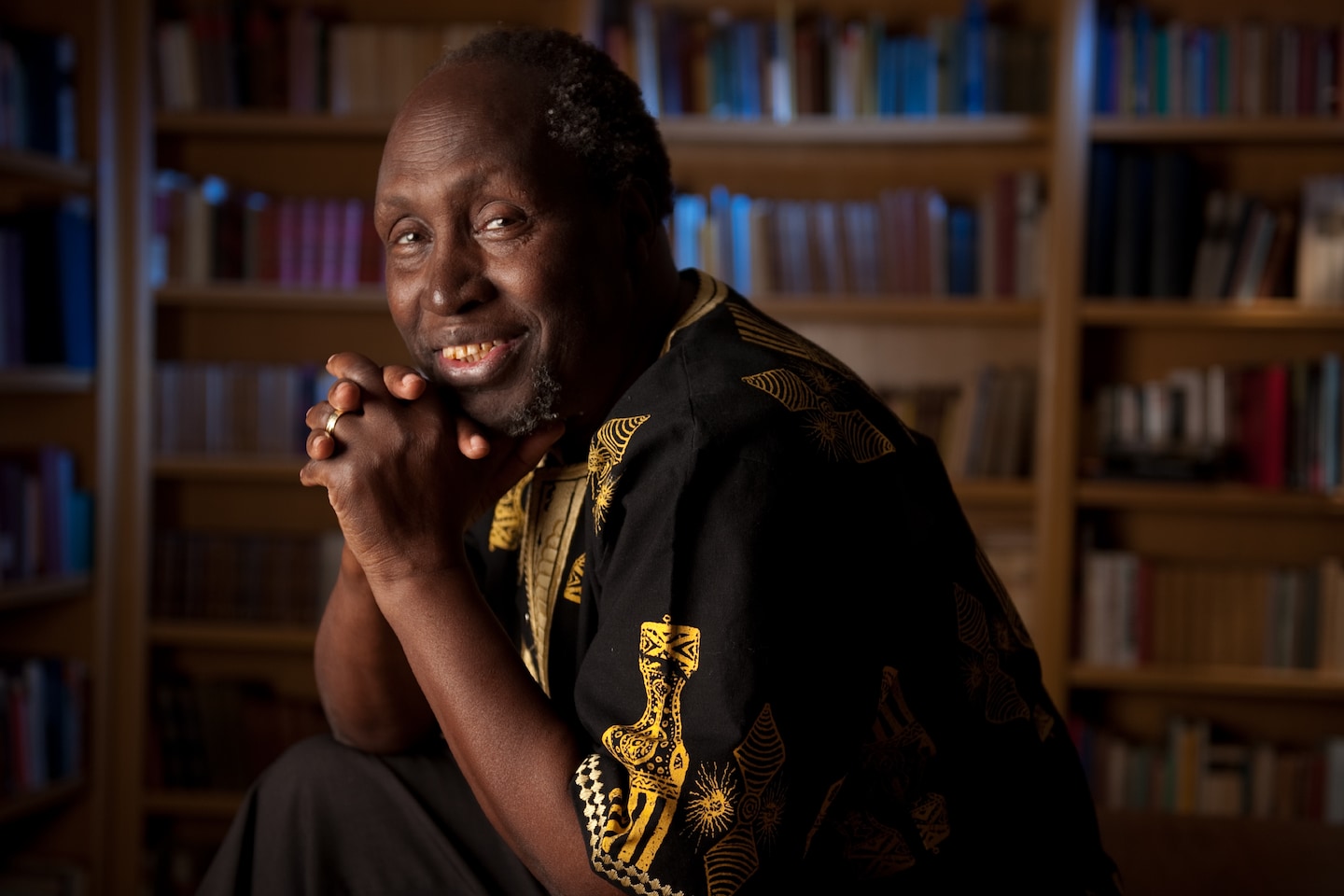

In the vast body of work produced since — novels, story collections, plays, essays and more than one memoir — Ngugi has grappled with the colonial era. In fiction, he’s dramatized the violence of British rule in his homeland. In his nonfiction, Ngugi has documented his own period of politically motivated imprisonment. Later, in his 1986 work “Decolonising the Mind,” the writer argues for a literature that rejects European language altogether, to find a truly African art form.

His new work, “The Perfect Nine,” is best understood within this context. Though it bills itself as a novel, that very term is a product of a European sensibility. The subtitle — “The Epic of Gikuyu and Mumbi” — is more useful. The artist is no longer engaged by grappling with the legacy of colonial rule. Having shuffled off English itself (the work was written in Gikuyu, the language native to central Kenya), Ngugi turns his attention to his culture’s origins.

“The Perfect Nine” is a work of myth, rendered in verse; you can hear the voice of the person relaying the story (“I will tell the tale of Gikuyu and Mumbi/And their daughters, the Perfect Nine,/Matriarchs of the house of Mumbi,/Founders of their nine clans,/Progenitors of a nation.”) just as we hear Virgil laying out the story he’s about to tell in the first verses of the Aeneid.

I’m mindful of the irony in my using classical Greece as a way of understanding this book. This will be the Western reader’s point of access, and I think it useful to reflect on the relationship between oral tradition and contemporary writing. Is there a fundamental human desire for story, a way to explain the world around us? “The Perfect Nine” seems to answer that desire, telling the tale of Gikuyu and Mumbi, progenitors of the Gikuyu people. Rather like Adam and Eve, though they are not conjured by the divine Mulungu (“The Hebrews call upon Yahweh or Jehovah, and he is the same Giver./Mohammedans call Him Allah, and he is the same Giver.”), they simply arrive, at the start of this tale, in what we know is now Kenya: “And then they came to a mountain/Whose top touched the sky.”

Gikuyu and Mumbi’s daughters are legendary from birth — “Young men lost sleep in dreams of the beautiful ones” — and dozens of suitors come to court them. Their parents hold that the girls will decide who wins their hands; Gikuyu declares to the men, “There are a few hurdles you have to jump so you get to know one another.”

The daughters and the 99 men who wish to marry them are dispatched to the mountaintop, “the seat of the Giver Supreme,” where they will receive a blessing that will guide them into the future. The party is attacked by crocodiles. They are beset by ogres. Many die, but ultimately, the survivors are wedded to one another. These unions are the beginnings of nine clans of a single people; these are the people from whom Ngugi is descended.

“The Perfect Nine” has the hallmarks of myth: exaggeration, adventure, magic, humor. It made me think of my first exposure to classical narratives — Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaire’s 1962 illustrated storybook for young children (in heavy rotation in my household) and Edith Hamilton’s 1942 volume “Mythology,” which I read in high school.

The straightforward language of “The Perfect Nine” means this, too, could be a work for young readers, perhaps read aloud by an indulgent parent. Yes, there’s a bit of danger and a hint of scatology, but the Greeks are far more ribald. And while Zeus and his associates were forever raping women, “The Perfect Nine” feels comparatively feminist: “There was no saying this is men’s or women’s work./We did tasks according to ability and necessity and inclination.”

Myth is illogical. People are beautiful and heroic in a way they aren’t, usually, in real life. Events are heightened and odd, and might be resolved by inexplicable turns, like an ogre transforming into a vulture. Therein lies their pleasure. Myth reflects the illogic of the world itself, promising the reader the tangible lessons and narrative closure that reality rarely provides. We know the tales of Greece and Rome; they’re the foundation of Western literature. But there are myths in every culture, and literature is not simply a Western pursuit.

Rumaan Alam is the author of “Rich and Pretty,” “That Kind of Mother” and, most recently, “Leave the World Behind.”

The Perfect Nine

The Epic of Gikuyu and Mumbi

New Press. 240 pp. $23.99

[ad_2]

Source link