The Suffragists Fought to Redefine Femininity. The Debate Isn’t Over.

[ad_1]

When Kamala Harris stepped onto the stage in a high school gym in Delaware earlier this month, after Joseph R. Biden Jr. announced that he had chosen her as his running mate, she sought to define herself as many things — a senator, a Black woman, an Indian woman, a prosecutor.

But her most important role, the “one that means the most,” she said, is “momala” — stepmother to her husband’s two children, Cole and Ella.

In choosing to wear the mother badge, at the highest point in her career, Ms. Harris was inserting herself into a persistent mold that powerful women have long been expected to fit: the warm, maternal, likable figure who, as Joan Williams, professor of law and director of the Center for WorkLife Law, wrote in a The New York Times op-ed, is “focused on her family and community, rather than working in her own self-interest.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, both pro- and anti-suffrage leaders used ideas about what women “should” be to make their case for and against the right to vote. Both sides leveraged emerging printing technology and photography to engage in what historians describe as one of the first coordinated visual political campaigns in American history.

And the suffragists “were as savvy about the tools that they had at the time as protesters and activists are now,” using visuals to hone their message and create instantly recognizable branding, said Susan Ware, historian and author of “Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought For the Right to Vote.”

The result was vibrant propaganda from both sides that helped give rise to characters and tropes — from the power-hungry “man eater” to the modern, working woman who could juggle it all — that have been passed down through the decades and remain deeply ingrained in American culture today.

One recurring theme for the anti-suffragists — some of them women — was that women were supposed to be virtuous caregivers and that giving women the right to vote would detract from household responsibilities like caring for children, managing the household and “looking pretty,” Ms. Lange said in a phone interview.

There was an idea that these women, by advocating for their political rights, were “rejecting family life and their homes, the things that American women are — quote unquote — supposed to be focusing on,” she added.

Almost as soon as the demand for the vote was raised, opponents of women’s suffrage began arguing against it, often with visual media. They used prints that would be sold as décor to present their ideals of “motherhood” and “femininity” as diametrically opposed to the dirty world of politics and the aggressive pursuit of success in public life.

Imagery like this illustration created in 1869 by one of the era’s most prominent printmakers, Currier & Ives, often painted the women who were seeking the vote as “ugly, shameless monsters,” who threatened to upend the status quo, said Ms. Lange. They were often dressed in attire deemed scandalous — skirts that exposed ankles, short pantaloons or bloomers — and indulging in what would have been widely considered immoral behavior, like smoking, drinking or ignoring a crying baby.

“They were trying to attack women’s femininity, their sense of decorum and their respectability,” said Kate Clarke Lemay, a historian and curator at the National Portrait Gallery. “They were always being called things like ‘man eaters.’”

Some images, like this print below published slightly earlier in 1851 in the satirical publication “Humbug’s American Museum Series,” which showed a white and a Black woman demanding relief from domestic responsibilities, alluded to another concern raised by those who opposed expanding women’s rights — that it would disrupt social and racial hierarchies in the United States.

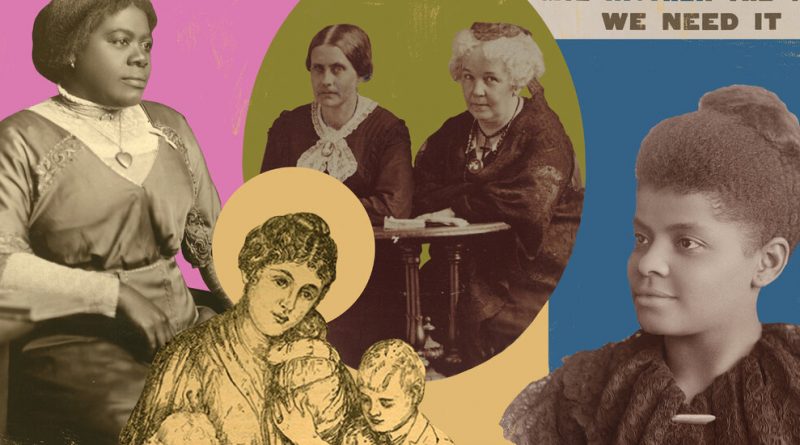

To counter their opponents’ attacks, in the 1870s the suffragists started sitting for portraits, which were sold to consumers to raise money for their cause. They hoped these images would help paint their movement in a more elegant light — a far cry from the cartoonish caricatures in circulation. Everything from their poses to their clothing was carefully considered to help propagate an image of intelligence, morality and refinement.

Many of the portraits — some of which were eventually published in the “History of Woman Suffrage” compiled by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and others — were aimed at showing the world that the suffrage leaders were “lovely women” and not “unattractive and unfeminine,” said Ellen Carol DuBois, historian and author of “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle For the Vote.”

“It was all part of building a visual identity of the movement,” she added.

Black suffragists, who were often marginalized in white suffrage groups, also created their own portraits, which they hoped would counter racist and sexist stereotypes. In the mid-19th century, the abolitionist and suffragist Sojourner Truth sold “cartes de visite” with her portrait when she went on lecture tours, as a way of establishing her respectability and ownership over her work. When later Black suffragist leaders such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary McLeod Bethune sat for their own portraits, they, like Stanton and Anthony, dressed in elegant clothing and wore jewelry to project wealth and refinement.

In the 1910s, as the movement shifted its focus toward a federal suffrage amendment and leveraged the national press to garner support for this campaign, the suffragists leaned into imagery of women as pure, heroic figures, Dr. Lemay said. Many illustrations from this period — like this image from 1915, published in a special edition of the humor magazine Puck, guest-edited by suffragists — were rich with ancient Roman symbols of equality and unity, or women modeled after Joan of Arc or Lady Liberty.

Suffragists such as Alice Paul — a member of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and founder of the National Woman’s Party — realized that by staging public spectacles like picketing the White House or leading a parade, and inviting photographers to document them, they could attract more attention to their cause in national daily papers (and eventually newsreels) that reached wide audiences.

In March 1913, Paul and NAWSA organized a massive suffrage parade in Washington, on the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Thousands of women all dressed in white gowns (denoting purity) and some even riding horses — like Inez Milholland, pictured above — marched through the capital.

News of the parade took up a large chunk of the front page of The Washington Post the next morning. The headline read: “Woman’s Beauty, Grace, and Art Bewilder the Capital — Miles of Fluttering Femininity Present Entrancing Suffrage Appeal.” The early caricatures of the suffragists as “ugly” had, it would seem, been successfully refuted.

At the same time, NAWSA was also working to flip the anti-suffrage depiction of motherhood on its head, making the case through posters and prints that suffrage wouldn’t detract from motherhood. In fact, they argued, not only was voting in the best interest of mothers, enabling them to advocate politically for issues they cared about, but being mothers would also make women better voters.

In 1906, the social reformer Jane Addams, a pioneer of the settlement house movement and a NAWSA board member, articulated this line of thought at the group’s annual convention.

“City housekeeping has failed partly because women, the traditional housekeepers, have not been consulted,” she said, and governments “demand the help of minds accustomed to detail and variety of work, to a sense of obligation for the health and welfare of young children and to a responsibility for the cleanliness and comfort of other people.”

This idealized vision of the suffragists as smart, beautiful, caring and motherly gave rise, Ms. Lange added, to the notion that a woman’s involvement in politics wouldn’t destroy domestic life. That the two things aren’t — and shouldn’t be — mutually exclusive, and that one feeds the other.

In the century that followed the ratification of the 19th Amendment — which banned discrimination at the ballot box on the basis of sex — these debates over femininity and motherhood have persisted. And the question of how women in the public eye navigate them has crept up again and again, compelling the growing number of women running for office “to negotiate their public images in terms of their statuses as mothers, wives, daughters and potential mothers,” Ms. Lange writes in her book.

We saw it this year at that Delaware high school gym, when Ms. Harris alluded to her Sunday night family dinners, which — she clarified — she cooked.

We saw it 2008, when Sarah Palin, the former governor of Alaska who ran for vice president alongside Sen. John McCain, consistently cast herself as a “hockey mom.”

And we saw it in 1984, when Geraldine Ferraro, who had just made history as the first woman to join a major party’s presidential ticket, was asked on a campaign stop in Mississippi by the state’s Commissioner of Agriculture whether she could bake blueberry muffins.

“I sure can,” Ms. Ferraro responded. “Can you?”