‘The Woman Who Stole Vermeer,’ by Anthony Amore book review

[ad_1]

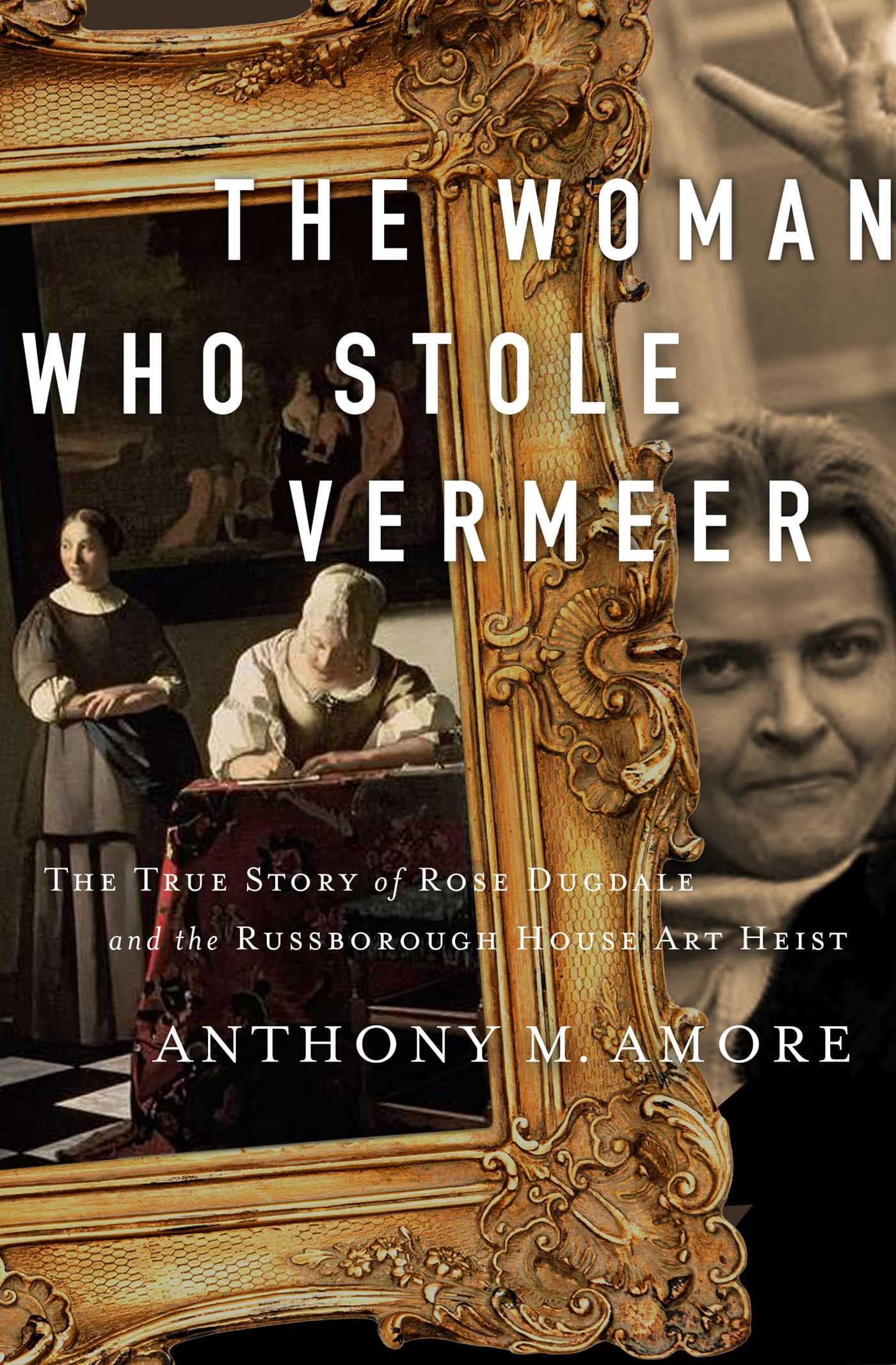

A ransom note demanded, in exchange for the art, half a million Irish pounds and the transfer to a Northern Ireland prison for Dolours and Marian Price, who were on a hunger strike in an English prison, where they were serving life sentences for their roles in London bombings the previous year. The Gardai who arrested Dugdale (whose wig and bad French accent fooled no one) found all 19 of the stolen paintings in her possession, among them works by Gainsborough, Velázquez, Hals, Guardi, Goya, Rubens, van Ruisdael and, most famously, the Vermeer painting “Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid.”

“The Woman Who Stole Vermeer,” Anthony M. Amore’s engrossing new book, is the first deep dive into the peculiar life of Rose Dugdale, the 33-year-old British heiress with a PhD who, at the time of her arrest, was also wanted for gunrunning, a bombing attempt and armed hijacking. She came from a “Downton Abbey”-esque world of upper-class comforts. In East Devon, she learned to hunt with her father and his British Army friends, who taught young Rose to creep through the grass like a soldier. Looking back on her idyllic childhood, Dugdale admitted it “was very good training in rifle practice.”

Before she fell in love with the Irish cause, Dugdale had been a contrary transgressor. She struck a bargain with her parents that she would endure a debutante season of balls and be presented to the queen if they would allow her to attend university. At Oxford, where she studied philosophy, politics and economics, she crashed the all-male Oxford Union while disguised as a man (she dressed habitually in scruffy men’s clothing) to denounce their exclusion of women. She got a master’s degree in philosophy at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts (her thesis was on Ludwig Wittgenstein); the letter of recommendation from novelist Iris Murdoch called her an “intelligent ‘all-rounder,’ ” who could one day be “an able administrator or a good university teacher.”

In the late 1960s, Dugdale’s increasingly radical beliefs led her to Cuba, where she labored in fields, attended lectures and enjoyed seeing “a revolution in the making.” She taught economics (and Marxism) while getting her doctorate at the University of London. Galvanized by the antiwar movement and the horror of Bloody Sunday in 1972, Dugdale began to involve herself in schemes supporting the IRA. Her militancy intensified during her complex relationship with Walter Heaton, a married, British, self-described revolutionary socialist to whom she gave a lot of money.

Dugdale began to concoct a series of increasingly wild assaults on British imperialism. In June 1973, with Heaton and other accomplices, Dugdale stole art and silver from the ancestral manse of her childhood in East Devon. When she was captured and put on trial with her accomplices for robbing her own family, although she furiously denounced her parents from the dock (affecting a working-class accent) as “gangsters, thieves and oppressors of the poor,” she alone was given a suspended sentence, the judge deciding the likelihood that she would “ever again commit burglary or any dishonesty is extremely remote.”

The following year, with Heaton in prison, Dugdale got involved with IRA renegade Eddie Gallagher, who participated in her scheme to hijack a helicopter and use it to bomb a military barracks in Strabane, a Northern Ireland border town at the heart of the Troubles. Dugdale’s cartoonlike plan to drop five milk churns, each packed with 100 pounds of explosives, failed.

A month later, in February 1974, a small, exquisite painting by Vermeer called “The Guitar Player” was stolen from Kenwood House, a museum in Hampstead, England. A call from a man with an Irish accent demanded an exchange: the picture for the transfer of the Price sisters to prison in Northern Ireland. A follow-up letter was strikingly like the ransom letter for the Beit paintings that would be sent a few weeks later. These art thefts were neither authorized by the IRA nor welcomed. The Price sisters wanted no part of any deal. The small Vermeer was left in a London church cemetery two days after Dugdale’s arrest in Ireland. Nobody was ever charged with that first Vermeer theft, but Amore asks a persuasive, if obvious, question: Was this Dugdale’s handiwork? His pursuit of an interview with his enigmatic subject was rebuffed.

When Dugdale was sentenced to nine years for the Beit theft, she declared herself “proudly and incorruptibly guilty.” Unexpectedly, she gave birth in prison to Gallagher’s child. They were permitted to marry while imprisoned, the only time they glimpsed each other. Dugdale was released in 1980, and today lives in Ireland, an unrepentant wise elder of the Sinn Féin political party.

Amore, the director of security and chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, has assembled a thorough correction to the Rose Dugdale story — although it is at times overly granular and occasionally careless with Irish geography. The book clarifies Dugdale’s seriousness and principles, pushing back against the superficial, adventure-seeking socialite label that has paired her erroneously with Patty Hearst.

The privilege and social rank that Dugdale repudiated gave her the trained intellect and discerning eye that made her the most notorious (and nearly the only) female art thief in history. If she were willing to take questions, perhaps she might have some insight about the unsolved 1990 Gardner Museum robbery, which has much in common with her Beit collection heist. Thirteen masterpieces, Vermeer’s “The Concert” among them, were stolen, and have never been found. The Gardner Museum is offering a $10 million reward for information leading to the return of the art. Think what Sinn Féin could do with the money.

Katharine Weber, the author of six novels and a memoir, spends part of every year in the West Cork village where Rose Dugdale was arrested in 1974.

THE WOMAN WHO STOLE VERMEER

The True Story of Rose Dugdale and the Russborough House Art Heist

Pegasus Crime. 272 pp. $27.95