Tunnel visionary: why was land artist Nancy Holt never given her due? | Art

[ad_1]

The story of land art is generally believed to be a tale of white men in weathered denim descending on what they thought of as the empty canvas of the American west in the 1960s with bulldozers and big ideas to make their work. But what of the women who were also making their mark? “Today, land art appears as an almost perfect distillation of the art world’s history of male privilege, with its conviction that man is entitled to space to roam, to make his mark,” critic Megan O’Grady wrote in 2018. “It is one of the contemporary art movements most urgently in need of reconsideration.”

A forthcoming exhibition at Lismore Castle in County Waterford, centred on the work of the late Nancy Holt, hopes to redress that balance. The Irish venue launches its post-lockdown programming with Light and Language, a group show looking at her legacy in contemporary art as a central member of the land art and conceptual movements. It is an uncommon opportunity to see a sizeable group of Holt works, many of which haven’t been exhibited in decades. There is a large-scale installation, several video and sound works, photography, drawing and a scattering of her “concrete poems”. The most recognisable piece of Holt’s is a mesmerising earthwork entitled Sun Tunnels – four cylindrical, concrete forms, large enough to walk through, installed in the desert in Utah.

Holt herself though is largely known as the wife of Robert Smithson, who is credited with founding the land art movement in the late 1960s and making its instant cover star: Spiral Jetty, that giant coil of white rock extending into the red waters of Utah’s Great Salt Lake.

Holt was wedded to Smithson’s legacy, too. After his death in a plane crash in 1973 at the age of 35, she stewarded his archive – and ensured his enduring fame – until she died in 2014. That same year, and at her behest, the Holt Smithson Foundation was set up to look after both artists’ estates. This show is part of that programme.

“It’s that classic thing – that female artists were just invisible,” says director of the foundation, Lisa Le Feuvre. “They were there, they were doing things, and they weren’t seen.”

Holt was born in Massachussets in 1938. She graduated from Tufts University with a degree in biology but it was moving to New York in the early 1960s and meeting artists, including Smithson, that really got her thinking. In 1966 she started making her series of concrete poems, and from the following year, as Le Feuvre puts, “she took language out into the landscape”.

Stone Ruin Trail I is a kind of custom-scored walking tour of a wooded ruin in New Jersey. Holt gave friends a two-page set of hand-typed instructions along with detailed photographs, noting the things (a roped entrance, a metal beehive, a castle-like structure, a glacial boulder) that caught her eye. That approach – observational, methodical, inclusive – was a constant throughout her career.

Our life indoors is intertwined with life outside, with the whole planet, actually

The Lismore show includes a 1969 piece entitled Trail Markers: a series of photographs of the orange dots spray-painted on rocks and trunks to mark British rambling pathways. She was fascinated when she saw them on Dartmoor. She described them as a ready-made artwork.

Holt was always serious. Her journals show how other artists loved talking through ideas with her. She was very close to Michael Heizer, Richard Serra and Joan Jonas. She exchanged concrete poetry by post with Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt. But when I ask Le Feuvre if the men saw her as a peer, she answers: “Yes, but.” They valued her input . But she wasn’t exhibiting in the same places they were. Similarly, it’s not that critics were dismissive of her work. They just didn’t mention her at all.

Smithson’s recognition of her support is without question. She shaped his writing (she was a subeditor at Harper’s Magazine; he is thought to have been dyslexic). Some say she shaped his ideas, too. She travelled west on location recces with him and if his earthworks were visible in Manhattan galleries, it’s because of the films she made. “It’s Nancy’s time now,” he said in 1970. “My job is to help her.” You get the sense that if his life had not been cut short, he would have as well.

This sideline of Holt’s as a subeditor is instructive. It’s a job that requires precision, curiosity and self-effacement in equal measure. You’re as invisible as you are invaluable, and you handle words, and other people’s voices, with great care. So too in Holt’s work. The big names of the movements she’s associated with – Heizer, De Maria, Smithson, James Turrell – are known for impossibly large sculptural impositions on the land that are more about the artists’ themselves than they’re likely to admit. By contrast, Holt was attuned to the intangibles, the structures and systems that connect us to the land.

Boomerang, on view at Lismore, is a video she shot with Richard Serra. You watch her talking for 10 minutes while she listens to what she’s saying, fed back to her over headphones. The shifts and slippages in understanding caused by that feedback delay seep into her improvised monologue, and if the tech – and her diction – give away the work’s age, the experience is all too familiar. It speaks of displacement and disconnect.

The centrepiece of the show is the 1982 installation, Electrical System. The first of her System Works, it is a flowing array of steel conduit connected to more than 100 lit lightbulbs, that fills a room. The aim, she said, was to externalise and expose the hidden networks (for water, ventilation, electricity) that tie the built environment into the landscape. In 1986, she installed a structure of steel piping that was dripping oil in a gallery in Anchorage just hours away from the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. The latter had for years been leaking oil, too. “These works are all political,” she told an interviewer shortly before she died. “Our life indoors is intertwined with life outside, with the whole planet, actually.”

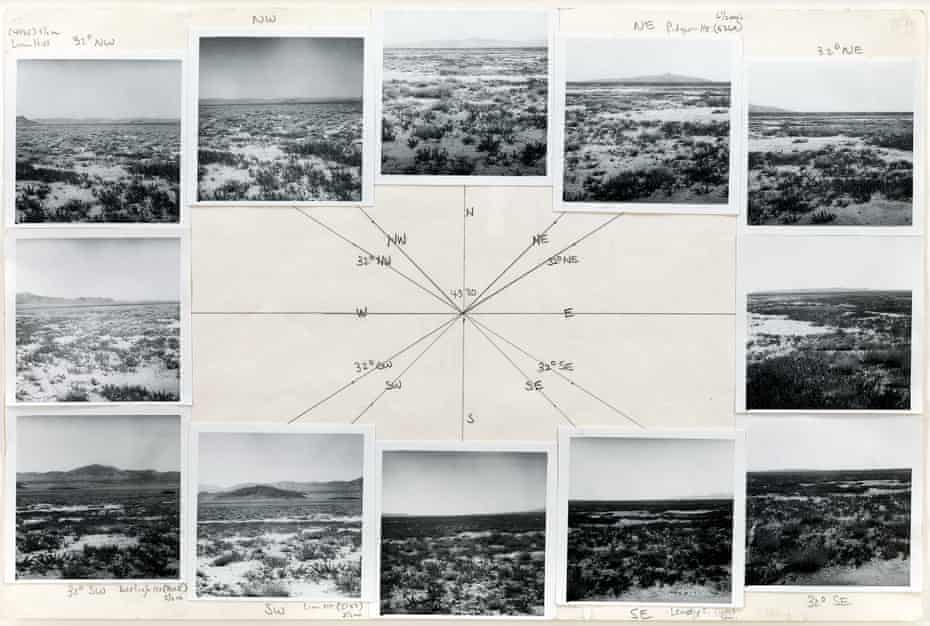

Sun Tunnels, Holt’s masterpiece, connects to systems much vaster. Made between 1973 and 1976, in the Great Basin Desert in Utah, it comprises four concrete tubes on an endless plain of scrub and dust. They’re arranged in an X in such a way as to frame the sun at the solstices. In between, they filter starlight and moonlight via perforations that correspond to the changing constellations. In the mirage-inducing desert heat, the whole thing almost disappears from afar; up close, it offers shelter. In 2018, it became the first earthwork by a woman to be bought by the Dia Art Foundation – the custodians of the era’s other major works.

Holt was a feminist, but resisted being associated with her feminist peers. She wanted recognition for her art, not her politics. When invited to make temporary pieces for exhibitions, she would sculpt them so well they’d be impossible to dismantle. And then she’d refuse to gift them to the institution. In an interview in 1978, she was asked if someone could own the Sun Tunnels. Yes, she replied, and they’d have to buy them. “She would not back down,” says Le Feuvre. Holt was making sure that her voice was there to stay.

[ad_2]

Shared From Source link Arts