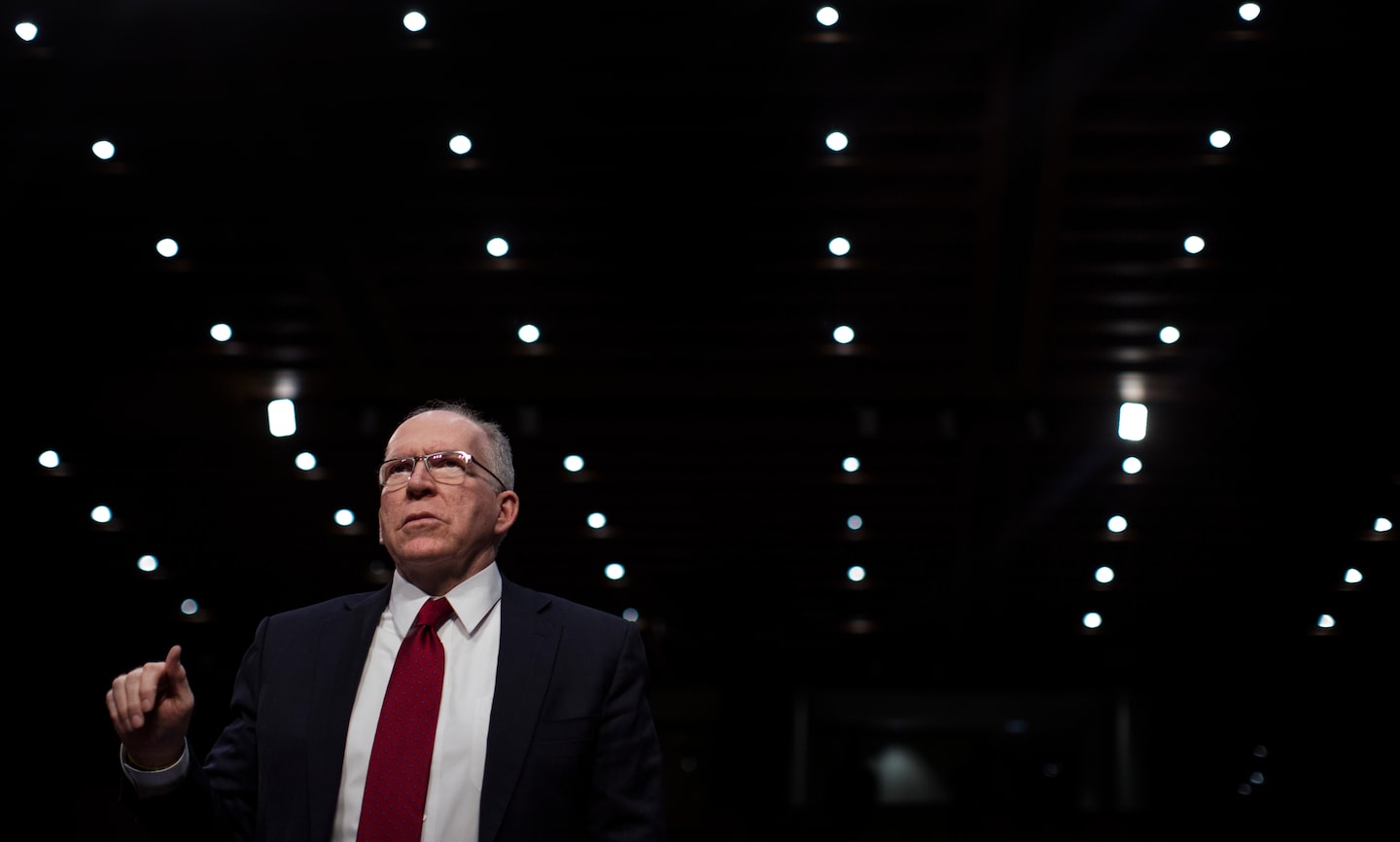

Former CIA director John Brennan takes on Trump, and doesn’t hold back

[ad_1]

“Undaunted” begins and ends with his fateful collision with Trump. The story starts on Jan. 6, 2017, when he went with other leaders of the intelligence community to brief the president-elect on Russia’s covert meddling to help him in the 2016 campaign. Before even meeting Trump, Brennan was wary of the president-elect’s “renown for playing fast, loose, and without principles.” Because of Trump’s “strange obsequiousness” toward Russian President Vladimir Putin and his “disdain” for U.S. intelligence, Brennan writes, from that first moment, “I had serious doubts that Donald Trump would protect our nation’s most vital secrets.” He says he left the meeting with a “dark feeling,” then headed to the wake for his father, Owen, who had just died.

It’s an ominous opening scene, worthy of a Wagner opera. For Brennan — and Trump, too — what has followed has been darker still. By mid-2018, Brennan was taunting the president on Twitter: He called Trump’s deference to Putin at the Helsinki summit “nothing short of treasonous” and said Trump was “wholly in the pocket of Putin.” He has never relented, despite Trump’s revocation of his security clearance and his loss of speaking income and corporate positions. At the book’s conclusion, he writes that he is “undaunted” by Trump, as the title boasts.

Trump’s circle appalled Brennan from the start, as his book makes clear. First buddy Lindsey O. Graham, the senator from South Carolina, appeared driven by “craven politics.” Rep. Devin Nunes, for a time chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, was neither “smart” nor “genuinely interested in national security.” Mike Pompeo, who succeeded Brennan as CIA director before becoming secretary of state, “solidified his reputation of putting loyalty to Donald Trump above commitment to country.”

Brennan seemed convinced that Russia was manipulating Trump. How did a former CIA director come to this startling judgment? He doesn’t present much new evidence. He writes that his suspicions began in July 2016, after he conducted an all-source review of “everything relevant to Russian interference in elections.” He then asked for an urgent meeting with President Barack Obama and told him, “Mr. President, it appears that the Russian effort to undermine the integrity of the November election is much more intense, determined, and insidious than any we have seen before.”

Sen. Mitch McConnell, as majority leader a member of the “Gang of Eight” that Brennan briefed on this same intelligence, rejected it with a conspiratorial view that has become a Trump talking point: “One might say that the CIA and the Obama administration are making such claims in order to prevent Donald Trump from getting elected president.” Brennan says he was “completely gobsmacked” by McConnell’s partisan cynicism.

Perhaps the strangest aspect of the Russia meddling story is why Obama didn’t act more forcefully to stop it. Here, Brennan is revelatory. Obama feared that if he took tough countermeasures against Moscow’s cyberwarriors, it might “prompt the Russians to recoil or to step up their election interference campaign, making matters worse.” The result, says Brennan, would have been “the specter of an escalatory spiral of cyberattacks.” Obama was cautious to the point of being intimidated, it seems.

For students of the CIA, this book is a narrative of life in an institution that is at once rigidly bureaucratic and toxically tribal. Brennan had hoped initially to be an operations officer, but he withdrew, agreeing with a colleague that “you do not seem to have the personal traits that would lend themselves to meeting, developing, recruiting, and handling foreign assets.” He instead chose the alternate path of analysis, and he made his way up the ladder as an Arabic speaker and Middle East expert. He learned the analysts’ technique of ducking questions they couldn’t answer, known as “going dumb early.”

As an analyst, Brennan was bruised by a CIA culture that celebrated the derring-do of the operators. As I’ve written elsewhere, these nasty rivalries are closer to “Mean Girls” than to anything you think you’d find in a modern intelligence agency. You can hear decades of resentment in Brennan’s complaint about the “insularity, parochialism, and arrogance” of the operators. He had his revenge as director, with a 2015 modernization plan that created “mission centers” that fused analysts and operators — a reform that, for all the griping at the time, still largely stands.

Until the Trump impasse, the central strand of Brennan’s story had been America’s deepening — and sometimes self-destructive — war on al-Qaeda terrorism. Brennan says his “most egregious” error was not speaking out against waterboarding and other interrogation techniques he knew were morally wrong.

But Brennan, who shied at the idea that the CIA’s job was “stealing secrets,” assumed an increasingly large role in the government’s killing machine. While he was Obama’s homeland security adviser from January 2009 to December 2015, he writes, Obama approved 473 strikes that killed between 2,372 and 2,581 enemy combatants and between 64 and 116 civilians. (The civilian toll seems very low, relative to estimates by human rights organizations, but Brennan claims it’s accurate.)

During those years, Brennan had regular contact with Vice President Joe Biden, about whom he makes some intriguing comments. In his view, Biden was wrong to advocate for a withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 and wrong about the raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan, that killed Osama bin Laden. (Biden favored a missile attack rather than a helicopter raid.) But he was right to warn Obama about the consequences of drawing a “red line” against chemical weapons in Syria, telling the president, “Big nations can’t bluff.”

Most of all, Biden was good at getting consensus. When there was a bitter dispute between Brennan and Sen. Dianne Feinstein over a Senate committee report on torture, the vice president brokered a deal, declaring, “We have to get this behind us, folks.” Brennan describes Biden’s trademark upbeat voice: “Come on, folks. . . . We’re the United States of America. We can do this.”

Even when he’s recounting such moments of compromise, Brennan emerges in his account as a proudly stubborn man. He refers often to this trait, admitting that on one occasion when he was overly rigid, a CIA colleague bluntly told him to “stop being a jerk.” Stubbornness can be an admirable quality when it’s anchored in principle, as Brennan’s is. But it conveys a kind of vanity, too, a moral self-righteousness. It’s telling that when Brennan was a young Irish Catholic boy in New Jersey, he didn’t just aspire to be a priest — he wanted to be the first American pope.

What do we make finally of this man who ran at Trump with his head? I wrote in early 2018 that I feared that because of Brennan’s attacks on Trump, “conspiracy theories about an imaginary ‘deep state’ will gain more traction, and the cycle of national mistrust will get worse,” feeding a belief among Trump supporters “that the real conspiracy was inside the intelligence community.” That worry is stronger than ever. Trump supporters will wrongly see the book as vindication for their argument that Brennan was out to get Trump from the beginning.

A lesson, perhaps, is that former CIA directors really do need to be careful about their public comments, lest they tarnish the reputation of their former agencies. Brennan spent a career protecting America in secret. When he began to speak out publicly, indignantly, it was impossible to stop. He may have been right, but in the process he damaged himself — and the idea that intelligence professionals should keep their distance from politics.

Undaunted

My Fight Against America’s Enemies, at Home and Abroad