Harry Smith b-sides collection shows a dark underside to early American folk music

[ad_1]

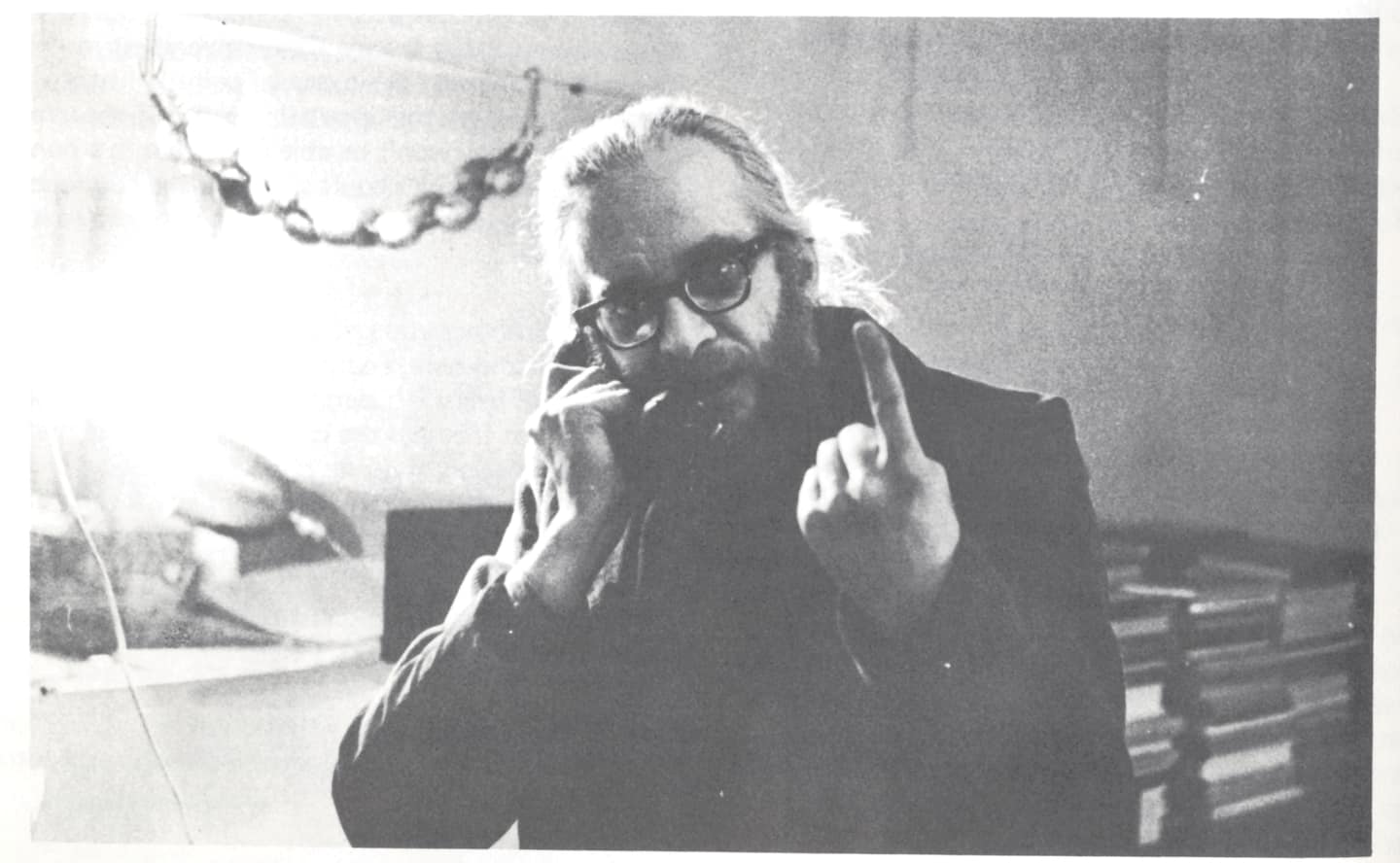

An experimental filmmaker, artist, mystic and collector of everything from paper airplanes and Seminole textiles to Ukrainian Easter eggs, Smith was best known for one particular collection: his thousands of old 78 rpm shellac records, focused on blues and hillbilly music, two early American music forms marketed to Black and White audiences, respectively. At the height of the McCarthyism witch hunts in 1952, Smith finally presented this personally logical and quasi-mystical collection to the public as “The Anthology of American Folk Music.”

The six LPs and 84 songs are always revelatory and often magical. Artist Bruce Conner encountered the collection in a Wichita public library and heard it as “a confrontation with another culture, or another view of the world . . . hidden within these words, melodies, and harmonies . . . but it’s here, in the United States!” A scene seemingly emerged overnight sown from its seeds and the AAFM’s devotees include Dylan, Woody Guthrie, John Fahey, Joan Baez, the Grateful Dead, and a litany of others well into the 21st century, such as Nick Cave and PJ Harvey, DJ/rupture and Beatrice Dillon. As Fahey once put it: “The Anthology of American Folk Music is a religion.”

Writing about the set’s cumulative effect, Greil Marcus noted: “For the first time, people from isolated, scorned, forgotten, disdained communities and cultures had the chance to speak to each other, and to the nation at large.” To its listeners, it presented a vision of America never quite glimpsed before. An acolyte of Aleister Crowley, Smith liked to frame “Anthology” as a cast spell.

But what is the inverse of this spell? What America can you perceive when you assemble “The Anthology of American Folk Music” using only the unselected songs from Smith’s records? What story does the flip side of a record tell?

This month, the Grammy-winning Atlanta-based archival label Dust-to-Digital released “The Harry Smith B-Sides,” a four-CD box set that follows the sequence of the original. A project some 16 years in the making, label heads Lance and April Ledbetter worked with folk collectors Eli Smith and John Cohen to complete the monumental task. It reveals a less mystical, more messy undercarriage to the recordings Smith first brought to the masses. “I think hearing all the same artists in the same order as Harry created for ‘The Anthology’ presents a sort of alternate universe take on his compilation,” Ledbetter wrote via email, comparing the process to a John Cage chance experiment: “Once we started flipping the records over and playing the other sides, we were in a setting of chance where we didn’t know what we would find.”

From venerated artists of country, folk, blues and bluegrass like the Carter Family, Blind Willie Johnson, Charley Patton and Dock Boggs to crackling jug bands and Cajun fiddlers, the flipsides revealed tropes ranging from salvation to anxiety; earthly sorrow to ribald dental work; the boredom of hell and a telephone line that stretches to heaven; celebratory moonshine and sentient pork chops. The songs might be less iconic than those selected for the “Anthology”, but they are more idiosyncratic.

The set will no doubt lead to questions like: how did Uncle Bunt Stephens get a sound as sorrowful and joyful out of his fiddle on “Louisburg Blues”? How could Smith have not selected Henry Thomas’s “Bull-Doze Blues,” one of the most ecstatic songs of the idiom? (Fans of Canned Heat or the “Woodstock” film will instantly recognize the iconic song, recast as “Going Up the Country.”) How is it that a 17th century melody that appears on “Moonshiner’s Dance Part Two” wound up being sung at my young daughter’s story time? Which is to say that what might seem like the distant past might still be very much in our present.

Most damning though are the handful of songs that depict violence against women and casually drop racial slurs, revealing the ugly underside that is American culture, one rooted in violence and racism. In the wake of this summer’s Black Lives Matters protests, the Ledbetters made the anguished decision to remove three songs entirely from the set. “The comparison of those songs to the Civil War monuments in city centers is a good one,” Ledbetter said. “Just like taking the statues down and placing them in museums, the same could be said of the tracks containing racist language. We are not trying to erase history . . . we just don’t want to shine a spotlight on racist songs.”

Bill & Belle Reed’s “You Shall Be Free” is a foundational song for both Guthrie and Dylan, but this version freely uses the n-word. On “Henhouse Blues” the Bentley Boys use the n-word and rue that frightful day when men will have to mind the kids and women can wear pants and become president. But the most offensive selection comes from Uncle Dave Macon.

It’s hard to discuss early American popular music without Macon, a vaudeville performer in the early 20th century who became the first star of the Grand Ole Opry, rightfully deemed “the grandfather of country music.” The nimble banjo picking interplay between Macon and Sam McGee sets a rollicking backdrop to lyrics about whipping and gagging his wife and then boasts about “farming the n—- trade.” On the box set, there are five seconds of silence where these three tracks would be.

Lomax Archives curator and box set contributor Nathan Salsburg acknowledges the difficulty of excising this musical tradition from its roots in minstrelsy. “Black and white players — to some extent — trafficked in blackface and those songs became a part of the folk tradition,” he wrote via email, explaining the first two deleted songs are straight from that form of entertainment. “Macon has some minstrel elements, but he’s also just flat-out racist — and misogynistic — as hell.”

For Sarah Bryan, editor of the Old-Time Herald and contributor to the box set, she says the reckoning with the ugly racism of early American music is long overdue: “Early country music is unfortunately rife with racist content. It’s a lot deeper than placement of words; it’s the whole American culture that underlay the music, and what today’s culture has inherited from those times, for better and for worse, and which parts of that inheritance should be kept and which emphatically discarded.”

There’s plenty to critique in Smith’s original presentation, from the lack of many ethnic minorities to including just one artist from above the Mason-Dixon Line. But by choosing the other sides of these respective records, Smith seemed fully cognizant of such underlying racism and did his best to steer away from such sentiments and instead present “the better angels” of America’s nature. One of Smith’s sly moves with the original “Anthology” was that he “successfully desegregated the collection by not indicating whether the singers were white or black,” according to Cohen’s liner notes. Leaving off the race of the performers, Smith let the music speak for itself while also presenting a vision of America that might not be cleaved solely by skin color.

That wasn’t the only divide it sought to bridge. As set curator Eli Smith notes: “Harry Smith dropped an extraordinary rural working class culture bomb on a New York City world of artists, bohemians, radicals, and city musicians . . . melding urban with rural, old forms with new times, Northerners with Southerners, immigrants with natives.” Smith’s vision of America could transcend such binaries, making beatniks go for the music of coal miners, hippies dig the psychedelic sound of the banjo, and good ol’ boys smitten for Mississippi John Hurt’s fingerpicking prowess.

Divergent forces in our society want to scrutinize this more disgraceful past, while others wish to suppress it once more. It’s a fine line between censorship and acknowledgment, but a tendency to gloss over and ignore this sordid past of ours that continues to afflict us, from the Great Depression to the coronavirus era. Singer Rosanne Cash understands both this urge to change and the heritage underlying it. What seems like the distant past is still here with us. A contributor to the box set, she wrote via email: “The racism: it hurts and humiliates. It humiliates Black people, and it humiliates the singer, even when he or she didn’t know that they were participating in degradation. I can’t excuse it and say, ‘oh, it was another time.’ It’s all ‘another time’. Now is ‘another time.’ ”

But her relationship to this music runs deeper than most. Through her father Johnny Cash’s second marriage to June Carter, she had an intimate connection with the music of the Carter Family, featured prominently on this set. “These songs mean more and more to me the older I get,” she wrote. “In my youth, these songs were curiosities, period pieces; I listened as an observer. Now they are part of my background consciousness; they are deep in my DNA — more so than I knew. They are like individual ghosts who travel with me. It comforts me that they are there.”

These B-sides show how such ghosts haunt — yet can also illuminate — us still.

[ad_2]

Source link