‘Human Nature’ book review – The Washington Post

[ad_1]

Just as front-line workers have been pleading with people to wear masks and practice social distancing, environmental activists have been trying to get us to wise up to the consequences of our actions. If we are visual learners, perhaps the 12 photographers featured in “Human Nature: Planet Earth in Our Time” can finally get through.

“These photographers all share one important similarity: They remind us that each and every one of us holds the power to create change through the everyday choices that we make: what we choose to eat, what we purchase, how we get to work, who we vote for, which businesses we support,” write editors Geoff Blackwell and Ruth Hobday in the book’s introduction. “We all have a role to play. But, we all must begin to act and act now.”

The book includes first-person narratives from each photographer, documenting their careers, their inclinations toward conservation and the specialties that have taken them to deserts and ice floes, above the clouds and under the waves. They discuss the troubling developments they’ve witnessed, from the proliferation of plastic waste in our oceans to the retreat of polar ice, but they also convey a sense of hope that we can still turn things around.

Following is a glimpse of the sometimes troubling, always stunning work featured in “Human Nature: Planet Earth in Our Time.”

Brian Skerry has been working at National Geographic for more than three decades, producing stories about oceans and waterways. “In the beginning I wanted to do stories about animals or places that interested me,” he says in the book. “I think in many respects it was self-serving — I wanted to do things that I felt were cool.” But something shifted as he worked on a story that would end up on the cover of National Geographic in 2004 — a look at baby harp seals in Canada that were being attacked both by hunters and by a decline in sea ice prompted by climate change.

“I’ve often said the ocean is dying a death of a thousand cuts and that unlike in the past, we have to understand that the ocean is not too big to fail,” Skerry says. “I think we are living at this very special and pivotal moment in history where, maybe, for the very first time, we actually understand both the problems and the solutions. And the question is, will we do the right thing and work on those solutions, or will we simply bear witness to the destruction?”

Born and raised in the Netherlands, Frans Lanting studied to be an environmental economist before pivoting to photography. “I’ve been doing this work now for four decades and in the last few years we’ve started a series of expeditions to places that I know well from earlier projects to document them again,” he says. “There’s a massive retreat of nature, especially in the tropics and sometimes I gasp when I see what has happened in the past few decades.”

But for Lanting, it’s not all doom and gloom. In Monterey, Calif., where he has lived for decades, he has witnessed scientists, politicians and private citizens work together to revive a damaged ecosystem.

As a photographer and filmmaker, Ami Vitale has traveled to more than 100 countries to document life around the globe. A pivotal moment came in 2009, when she first met Sudan — then one of eight remaining northern white rhinos in the world — before he was transported from a Czech Republic zoo to Kenya in “a desperate, last ditch effort to save an entire species,” she says. It didn’t work. Vitale traveled to Africa in 2018 to document the animal’s dying days: “This gentle, hulking creature was the last of a species who had survived for millions of years, but he couldn’t survive us; he couldn’t survive humankind.”

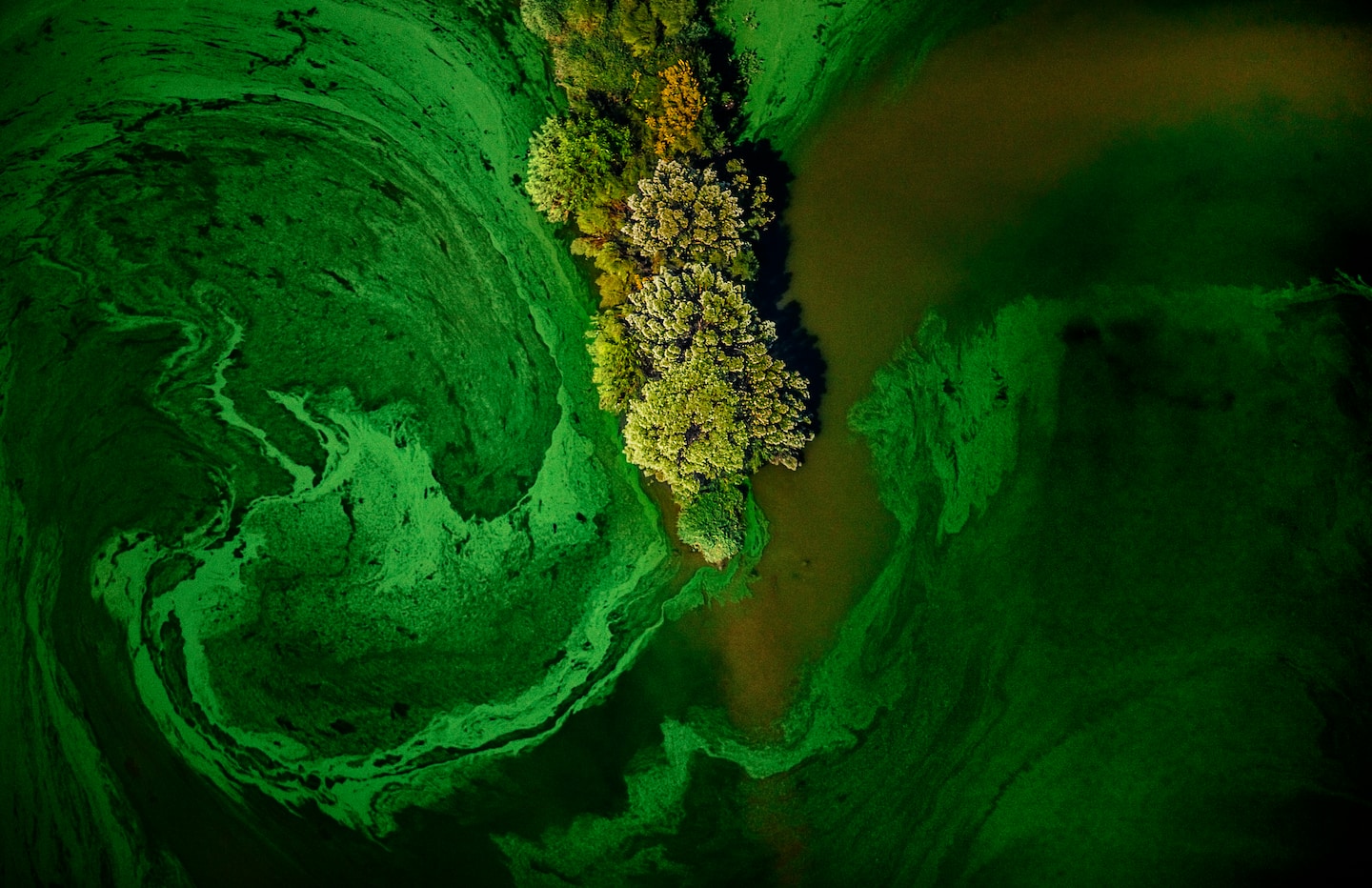

J Henry Fair’s large-scale aerial photographs are both gorgeous and disturbing. The South Carolina native illuminates the effects of industrial pollution on the landscape, and to do so, he has flown over oil refineries in Texas, fracking sites in Pennsylvania, a coal mine in Germany and a massive oil tank in Canada.

“I want my photographs to work on multiple layers,” he says. “They must be beautiful and the irony of making something beautiful out of something terrible comments on the irony of life in the modern world, where each of us, no matter how conscientious, must realize that we’re stealing from our grandchildren by not living a sustainable life.”

Stephanie Merry is editor of Book World.

Human Nature

Edited by Geoff Blackwell and Ruth Hobday

[ad_2]

Source link