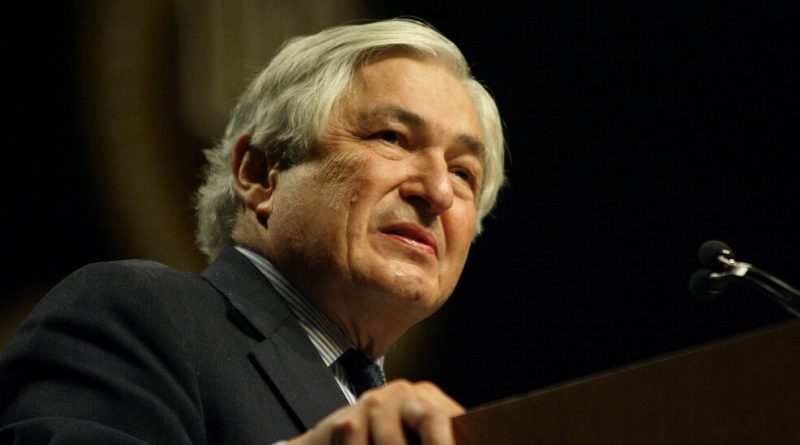

James D. Wolfensohn, Who Led the World Bank for 10 Years, Dies at 86

[ad_1]

James D. Wolfensohn, who escaped a financially pinched Australian childhood to become a top Wall Street deal maker and a two-term president of the World Bank, died on Wednesday at his home in Manhattan. He was 86.

His daughter Naomi Wolfensohn confirmed the death.

Mr. Wolfensohn was a force on Wall Street for years, helping to rescue the Chrysler Corporation while working for Salomon Brothers and running his own thriving boutique firm, before President Bill Clinton nominated him to lead the World Bank, the world’s largest economic development institution.

But he was more than a financier. He led fund-raising efforts as chairman of Carnegie Hall and headed a revival of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. An accomplished cellist under the tutelage of the renowned Jacqueline du Pré, he performed at Carnegie Hall on his milestone birthdays. And as a university fencing champion, he was part of Australia’s 1956 Olympic team, competing in front of his fellow Australians in Melbourne.

But his main legacy was his stewardship of the World Bank, to which President Clinton nominated him in 1995 after he had given up his Australian citizenship 14 years earlier to qualify for the job, only to be passed over.

Arriving at the bank’s Washington headquarters to begin his first five-year term, he found life there too comfortable and its staff members demoralized — a professional malaise, he said, that had them denigrating the bank to their families and even to the news media.

He immediately attacked the bank’s “complacency and insularity,” as he put it. He found that the bank’s emphasis on technocratic, market-based reforms was inhibiting its central mission: aiding the world’s poorest countries.

“I was throwing a grenade into an entrenched culture,” he wrote in his 2010 memoir, “A Global Life: My Journey Among Rich and Poor, From Sydney to Wall Street to the World Bank.”

A priority for Mr. Wolfensohn was to make field visits to poor nations less ceremonial than his predecessors had, and to listen to poor people themselves describe their governance, history and culture. He mounted a campaign against corruption in World Bank projects, breaking what he called “a wall of silence” on the subject. His efforts led to stepped-up audits and put the issue higher on the agendas of developing countries.

“He made it acceptable to talk about corruption,” said Hazel Denton, then a senior project economist for the bank. “Until his time in office, we tended to sweep the topic under the carpet in the interest of getting projects ‘done’ and getting loans disbursed.”

Another Wolfensohn initiative was to shift the bank’s policy on debt incurred by its mostly impoverished African and South American client countries. Instead of insisting on repayment, he sought to write off much of the debt.

“How, I reasoned, could you have a lending business to borrowers of low credit and then pretend that you would be repaid 100 percent on every loan?” he wrote. “I thought that any system that relied on this logic was doomed.”

Catching something of a popular wave, including support from Pope John Paul II (who cited the absolving of debt in Leviticus), World Bank directors in 1996 approved $500 million for a relief trust fund; three years later, they relaxed eligibility for faster and deeper debt relief.

Mr. Wolfensohn said he was particularly proud of having installed a high-speed communications network linking affiliates in 80 countries, allowing interactive video conferencing and distance learning. “Modest, he wasn’t,” declared Fauzia S. Rashid, a staff member who worked with him.

A Family Scraping By

James David Wolfensohn was born on Dec. 1, 1933, and grew up in Sydney, Australia, where his parents, Hyman and Dora Wolfensohn, had moved from London in 1928. The family, which included an older sister, Betty, was always in financial stress even though his father had at one time moved in the upper echelons of British society: He had met James Armand de Rothschild in the British Army and then served as his private secretary, before having a falling-out that the elder Mr. Wolfensohn never explained.

The family’s failure to establish itself in Australia weighed heavily on young James from about the age of 7, producing an obsession with monetary insecurity that carried long into his adult life.

As a child Mr. Wolfensohn“was always doing contingency planning in my head.” he recounted in his memoir. “I remember thinking that if I could have just 10 pounds, my life would be safe. As I grew older I would do calculations on scraps of paper and work out how long I could live on 100 pounds if I only ate cheese and bread.”

After early academic failures related to grade levels beyond his years — he entered the University of Sydney at 16 — Mr. Wolfensohn suddenly began to thrive under the intense mentorship of a renowned professor, Julius Stone, a friend of his father’s. He graduated in 1954.

During law school Mr. Wolfensohn obtained a clerkship with a top Sydney firm, Allen Allen & Hemsley, where a colleague introduced him to fencing. Preferring the épée to the saber despite not being tall and lean, he did well against world-class Italian and British competitors in the Melbourne Olympics before, by his account, becoming distracted and losing.

“The most exciting moment in his life was when he made the Olympics” as a confidence-lacking “colonial kid,” his wife, Elaine Wolfensohn, put it in an interview for this obituary in January. “It had an enormous impact on who he was, who he became.”

With full legal credentials, Mr. Wolfensohn worked on a major antitrust case involving American companies and then decided to apply to Harvard Business School. He eventually flew to attend the school free of charge because of his service in the Royal Australian Air Force Reserve.

While studying there he met Elaine Botwinick, a Wellesley senior who had grown up in Manhattan and New Rochelle, N.Y. They married in 1961 and had three children, Sara, Naomi and Adam.

Mr. Wolfensohn is survived by his children and by seven grandchildren.

After a brief stint with a Swiss cement company, Mr. Wolfensohn returned to Australia to work for a number of banks, including J. Henry Schroder, which sent him to its headquarters in London and then to run its New York office. But when passed over in London for the chairmanship of Schroder, a blue-blood bastion — he said the rejection had “shattered” his fragile sense of security — he sought out Salomon Brothers.

“I was being thrown into the deep end of the toughest business in New York,” he recounted.

After his modest British salary, he said, the idea of earning $2 million to $3 million a year “was both scary and exhilarating,” because this was his first job without what he called a financial safety net.

His Own Shop

Mr. Wolfensohn reorganized and built Salomon’s corporate department and helped rescue the Chrysler Corporation through a huge government bailout in 1979 — the largest in American history at the time. Some partners at the firm thought he had spent too much time on the Chrysler deal, however, and his relationship with Salomon soured.

He left the firm after Robert S. McNamara, the head of the World Bank, told him that he had put Mr. Wolfensohn’s name on a list of people who might succeed him. To qualify for the post, Mr. Wolfenson quickly became an American citizen, only to see the job go to Alden W. Clausen. (Mr. Wolfensohn later regained his Australian citizenship.)

Seizing the chance to fulfill a lifelong dream of owning his own business, he opened James D. Wolfensohn Inc., a boutique Wall Street adviser that immediately thrived.

One prominent deal came after Louis V. Gerstner Jr., chief executive of IBM and a board member of The New York Times Company, called to ask if Mr. Wolfensohn would assist in The Times’s purchase of The Boston Globe.

“I felt proud that he had picked us from among all the Wall Street firms, not because I had approached him but because of our reputation for skill and integrity,” Mr. Wolfensohn wrote in his memoir. “With the help of our distinguished neighbor and friend, Arthur (‘Punch’) Sulzberger, the chairman and publisher of The New York Times, and his immensely competent team, we made a successful transaction.”

Twenty years later, however, in a period of downsizing, The Times sold The Globe and other New England media properties for $70 million, far below the $1.1 billion it had paid.

Mr. Wolfensohn became chairman of Carnegie Hall in 1980 and helped raise about $60 million to renovate it after donating $1 million of his own. Ten years later he was invited to help rescue the financially ailing John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, also as chairman. As he wrote in his memoir, he found the Kennedy Center to be a “white elephant” badly in need of physical repairs and more energetic programming.

He also worked for decades on behalf of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., and was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

Mr. Wolfensohn was made an honorary officer of the Order of Australia in 1987 and received an honorary knighthood of the Order of the British Empire in 1995.

A Carnegie Hall Debut

At a dinner party one evening, Mr. Wolfensohn, who was 42 at the time, impulsively said that he had always wanted to learn to play the cello. Ms. du Pré had one delivered the next day and agreed to give him lessons on the condition that he would play a concert on his 50th birthday.

Seven years later, Daniel Barenboim, the pianist and conductor (and Ms. du Pré’s husband), reminded him of his pledge and told him that a private performance would not suffice. The concert would be chamber music at Carnegie Hall, Mr. Barenboim said, insisting that Mr. Wolfensohn, who had never played chamber music and never played in public, perform there. The hall was reserved; the date would be Dec. 1, 1983, his birthday.

A year of intense practice ensued, sometimes in hotel rooms around the world — all leading to a Walter Mitty-like performance before an audience of hundreds. Onstage with him were the violinist Isaac Stern, the pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy and other music royalty; the program consisted of works by Haydn and Schumann.

Similar concerts followed on Mr. Wolfensohn’s 60th and 70th birthdays, at the Library of Congress as well as at Carnegie Hall.

On joining the World Bank in 1995, Mr. Wolfensohn divested his stake in his Wall Street firm, where he had recruited Paul A. Volcker to join after Mr. Volcker had retired as chairman of the Federal Reserve. When his partners sold the firm for $210 million to the Bankers Trust Company, Mr. Wolfensohn invoked a clause in his own sale agreement to pocket $45 million in the bank’s stock, half of which he and his wife gave to a family foundation to support the arts, culture and health care.

Ten years later, when he stepped down from the World Bank, Mr. Wolfensohn formed Wolfensohn & Company, another boutique advisory.

His last major undertaking was in the mid-2000s as a special envoy for a diplomatic group known as the Quartet — made up of the United Nations, the United States, the Russian Federation and the European Union — which was seeking an Israeli-Palestinian peace deal in which Israel would disengage from the Gaza Strip. If the deal were struck, he was to help coordinate revitalization efforts once the Palestinian authorities had taken over the area, the U.N. said at the time.

However, the negotiations failed.

“The Middle East,” Mr. Wolfensohn grimly observed, ”turned out to be my mission impossible.”

Alex Traub contributed reporting.