Nuclear Workers Sickened In Secret US Government Training Exercise Demand Answers

[ad_1]

Lamey’s lungs were slow to recover. Two months after the exercise, a physical exam by the doctor at work showed that his “lung capacity had been reduced compared to previous examinations,” according to his sworn testimony.

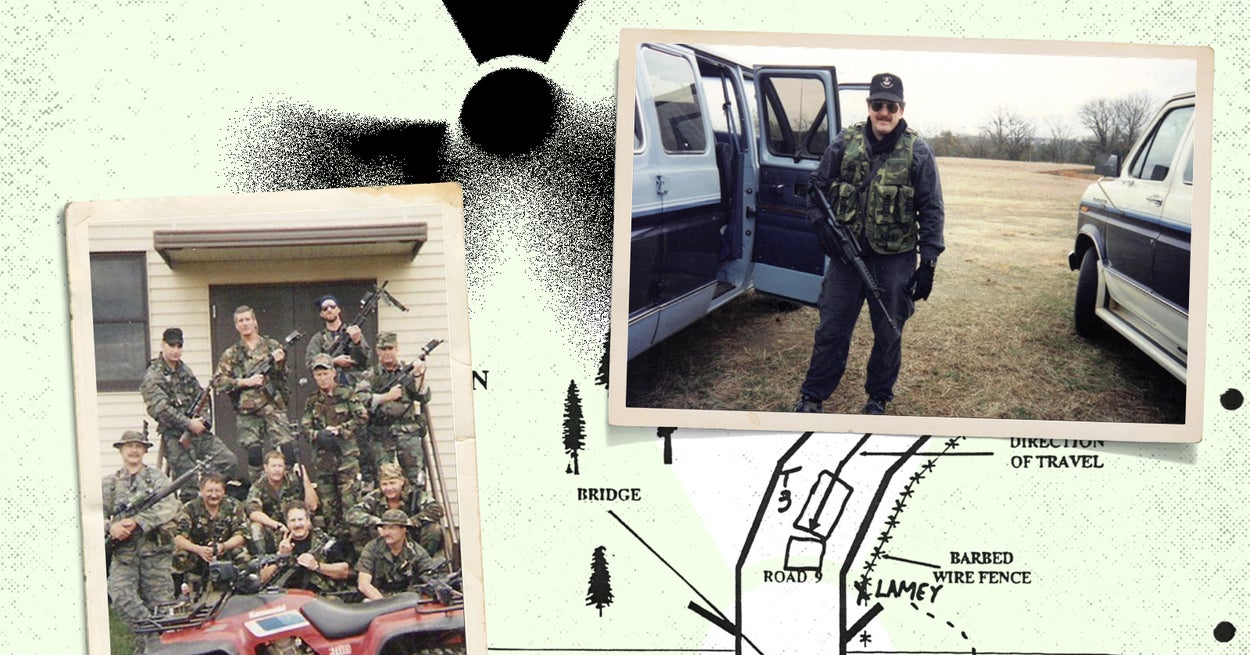

Lamey used to be an undercover cop, and he said that in one case he had to testify about events that had happened a decade earlier — something he was able to do only because he kept good notes. He leaned on that habit again, taking notes and collecting documents as he repeatedly pressed his supervisors for medical testing and status updates on various internal investigations into the incident, and he submitted a public records request for all documentation tied to his possible exposure.

Lamey concluded that there was a government “cover-up,” and shared thousands of pages of personal, internal, public, and legal records on the incident with BuzzFeed News.

The documents, combined with interviews, do not prove a cover-up. But they do show that the government’s response was haphazard and flawed. The government brought in a rotating cast of people to investigate what happened, and glaring possible explanations for what happened were never fully explored.

In the days and weeks after the exercise, contractors and government officials began looking into what happened, and one contractor even reached out to the CDC — but despite interest from the CDC, investigators never followed up.

By May 1991, officials were stumped but offered two tentative theories for what had happened: “unspecified allergic reaction to decaying pollen and vegetation” or “exposure to grenade smoke that had settled in concentrated pockets in low lying areas,” according to an internal report summarizing the preliminary investigation.

But by the investigators’ own admission, the grenade smoke theory couldn’t be a complete answer because “not all personnel who reported symptoms were exposed to the smoke.” Officials also weren’t fully convinced by the allergic reaction idea. The most they would say is that they couldn’t rule it out.

Seven months after the exercise, a top official from the couriers’ Transportation Safeguards Division, or TSD, was already saying it probably was too late to find out definitively what had happened, even while ordering further investigation. Published in February 1992, the resulting report was put together by health official David Anglen and indeed offered no explanation for the illnesses, although it dismissed many possibilities. Anglen declined to comment on the investigation.

Officials reported how they brought in a botanist from the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory to review the vegetation at the exercise location for plants that could make people sick (none were found). They also checked whether any herbicides were recently applied (none were), checked an unlabelled 55-gallon drum for contamination (none was found), looked for discolored or dead plants as a sign of chemical contamination (none were found), and sampled the air at the exercise site for hydrogen sulfide and methane (neither was found).

Perhaps more important than detailing what TSD had done so far, Anglen’s evaluation showed what officials had not done before and after the exercise: They had not checked the water or soil for radiation, heavy metals, or other pollutants.

TSD safety personnel spent very little time — less than one hour — checking the site of the exercise before it took place. In response to a courier raising concerns about the rivers being polluted, Anglen’s report concluded: “This potential hazard was not adequately addressed prior to the exercise.”

The report also detailed how a Savannah River Site official informed TSD that “there were ‘numerous’ radiation areas” at the nuclear facility site, yet the exercise site had not been checked ahead of time for possible radiation.

The report also mentioned how “at least four months after the exercise, some participants still are reporting experiencing respiratory symptoms that they believe are related to the exercise.” Martin Marietta had already implemented a medical review for their guards by this point, according to the report, and TSD planned to follow their lead.

Lamey and other couriers said this didn’t happen.

No blood or urine samples were taken, nor were tests for radiation or chemical exposure ordered for the people who reported symptoms in the hours, days, or weeks after the incident.

A month after the training, Lamey wrote the program director, Randolph Sabre, asking “to have a complete physical and full body count conducted, due to the fact that I am still coughing up some type of fluid.” Lamey noted how 30 days had passed and “DOE has not made any efforts to check any personnel that was apparently exposed.”

By the end of 1991, McIntyre was also asking for testing. Both Lamey and McIntyre were finally tested for radiation exposure in early 1992, almost a year after the exercise, through what’s called a full body count, which involves using a machine to scan for radioactive material in the body, and a special urine test.

According to McIntyre, his results came back normal, and he recalled being told by the officials conducting the tests that “after all of this time it would be unlikely that the tests would find anything significant.”

Lamey was also told that everything was normal on the full body count. His urinalysis was a different story: Trace levels of tritium were found. “[S]ince tritium has an effective half-life in the body of only ten days,” he recalled being told, “it is highly unlikely that this result is related to the exercise in which this individual was involved on 4/24/91.”

Meanwhile, the nine other couriers involved in the exercise who spoke to BuzzFeed News said they hadn’t been tested at all.