Pattern & Decoration: A Movement That Still Has Legs

[ad_1]

ANNANDALE-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. — What is art history made of? Everything that happened within a given period, location or style? Or is it just the best of what happened? These questions form an eternal opposition between inclusiveness and quality. They crop up — and sometimes openly conflict — in “With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art, 1972-85,” a rich, if flawed survey at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College.

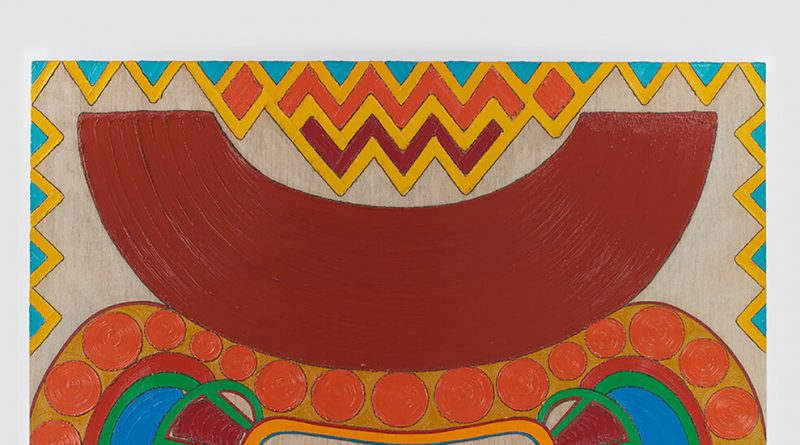

In the mid-1970s, the irreverent upstart movement Pattern and Decoration, or P&D, was one of the first cracks in the Minimalism-Conceptualism hegemony. The other was “New Image Painting,” an abstraction-tinged figuration named for its exhibition at the Whitney in 1978. But New Image never really cohered. In contrast P&D, at least for a while, was something of an onslaught. It favored patterns appropriated from a global array of textiles, ceramics and architecture but also from previously disregarded Americana like quilting, embroidery and cake decoration. A self-identified group, it was deliberately formed, and named, by a core of sympathetic artists that soon expanded to include numerous like-minded sensibilities.

It offered ravishing alternatives to mainstream art in both New York and Los Angeles (it was bicoastal) and to the general manliness of modernism. It disdained divisions between Western and Non-Western art; high and low and art and craft. It elevated women’s work and included many female artists. It was casual and unpretentious, too easy to like perhaps, but also proof that there was art after Conceptualism’s death-of-the-object stance.

P&D also had, for a while its own champion, the art historian Amy Goldin (1926-1978), who advocated Islamic art as a source for contemporary artists. While at the University of California, San Diego, Goldin taught two of the movement’s most prominent artists. One was Robert Kushner, who would start out in New York as a performance artist staging fashion shows of friends wearing lavish patchwork capes (and not much else) that he then started hanging on the wall; the exhibition sums up his progress in three works. Kim MacConnel meanwhile took to staining bedsheets with exuberant designs, achieving a very unpainterly flimsiness. Echoing both Matisse and Hawaiian shirts, MacConnel’s motifs also decorated sofas, side tables and lamps, as his environment happily attests here. Another avid proponent of the style was John Perreault (1937-2015), critic for the Village Voice and then the SoHo Weekly News, who organized“Pattern Painting,” the first large overview of P&D at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center in 1977.

The movement also had its own dealer in Holly Solomon, who opened her commercial gallery on West Broadway in 1975, and exhibited many of its artists.

How does P&D look 40 years later? Less interesting for itself than for the permission it granted succeeding generations of artists who weave, quilt, sew and make pottery without a second thought. Just as the critic Robert Hughes once cruelly referred to Color Field Painting as “giant watercolors,” too much of P&D could be called “giant wrapping paper,” pattern for pattern’s sake and lacks scale and punch.

The show has been curated by Anna Katz working with Rebecca Lowery, assistant curator for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, where it debuted in 2019. They have opted for inclusiveness over selectiveness, leaving no stone unturned. It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that the exhibition represents almost every artist who was in any P&D show anywhere. And there were many, according to the list in the show’s catalog. Reading it, you can hear small museums across the country sigh with relief: Here was something that was accessible, visually pleasing and easily transported, after all that Minimalist sternness, blankness and weight.

Early enthusiastic essays by Goldin and Perrault are included in the show’s handsome catalog, a veritable P&D handbook with a cover derived from Jane Kaufman’s “Embroidered, Beaded Crazy Quilt” (1983-85), which comes across here as among the movement’s few masterpieces. Katz approaches her subject from every angle, its relationship to feminism, multiculturalism and the counterculture, as well as its (now questionable) cultural appropriation and even its underlying debt to Minimalism (the use of repetition and the grid).

The six other essays include one by Lowery that focuses on a little-known site of P&D goings-on in Boulder, Colo., that especially nurtured the ceramic artist Betty Woodman, one of the movement’s mainstays. Her glazed deconstructions of vase-sconce combinations here have, like MacConnel’s efforts, an impeccable sense of color and scale.

Other standouts at the Hessel include tributes to wallpaper by Cynthia Carlson and Robert Zakanitch. Carlson has re-created her 1981 installation “Tough Shift for M.I.T.” by once more taking up a pastry tube to squeeze regularly spaced, unusually tactile little flowers across the walls of a gallery here. Wielding a big, loaded brush, Zakanitch created opulent enlargements of the more demure wallpaper he remembered from his grandparent’s house. Kozloff’s ambitious riffs on Islamic art using silk and canvas remain too close to their sources; these patterns were intensified by mosaic in her public works of the late 1970s and ’80s; her current P&D adjacent paintings may be her best.

Miriam Schapiro, who, like Kozloff, helped formulate some of the basic tenets of P&D, looks good in the catalog but is represented by “Heartland,” a horrible painting from 1985. Something earlier and better should have been chosen, although a blown-up detail of “Heartland” makes a fabulous endpaper in the catalog. Better works include a quilt-like painting made with stamped motifs by Susan Michod; Merion Estes’s “Primavera,” a fountain of pink brush strokes; and Mary Grigoriadis’s luscious paintings of giant, and archaic, architectural details. The Doric capital of “Rain Dance” reminds us that when first made, Greek temples were brightly painted.

Adding verve to the proceedings are relevant works by briefly aligned ’60s art stars: Lucas Samaras, Frank Stella, Billy Al Bengston, Alan Shields and Lynda Benglis, who is quoted saying “I was never really part of their gang.”

The show is least predictable and more rewarding as it ventures further afield, for artists whose efforts were related to but not usually part of the gang because, for one thing, they were not white. While Howardena Pindell’s work has been present in P&D shows almost from the start, other relatively new additions include the efforts of Al Loving, Sam Gilliam, William T. Williams, Emma Amos and most of all Faith Ringgold. In 1974, Ringgold painted bright geometries inspired by African Kuba cloth on narrow canvases and then, looking to Tibetan thangka, extended them top and bottom with — apparently — pieces of ersatz tourist blankets, sewn and appliquéd by her mother. They must be the most assertive scroll paintings you’ll ever see.

With configurations like this, a sleeker, less diluted “With Pleasure” emerges. Ours is a period of vital rediscovery of artists from the recent and distant pasts, but they don’t all deserve rescue from the dustbin of history.

Pattern and Decoration was pushed aside by the 1980s onslaught of Neo-Expressionism and Pictures Art. Yet, the example it set is more alive than ever, especially with so many non-Western artists drawing on their own craft traditions. A survey of P&D’s reverberations is by now too large to be encompassed with a single exhibition.

With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972-1985

Through Nov. 28 at Hessel Museum of Art at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. (845) 758-7598, ccs.bard.edu.

[ad_2]

Shared From Source link Arts