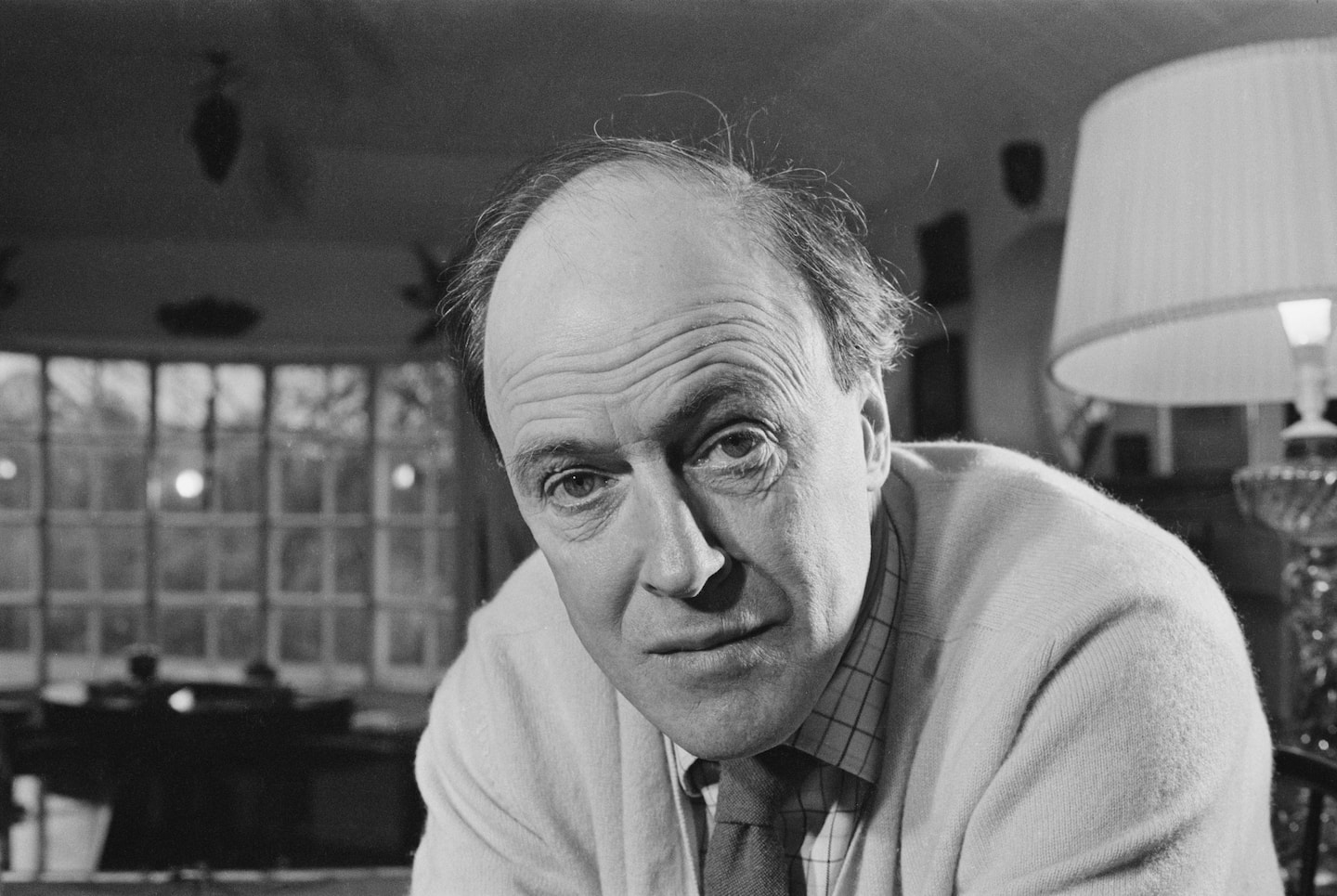

Roald Dahl was anti-Semitic. Do we need his family’s apology now?

[ad_1]

As apologies go, this one is scrumdiddlyumptious — a perfect concoction of corporate ingredients: Dahl’s slurs, only vaguely alluded to, are subsumed within a larger reiteration of how great Dahl’s stories are. Readers are reassured that through some fortunate miracle, his hostility toward Jews is another educational aspect of the author’s work: “We hope that, just as he did at his best, at his absolute worst, Roald Dahl can help remind us of the lasting impact of words.”

Dahl’s anti-Semitism has always been the unfriendly BFG in the room. The only mystery is what kept his richly rewarded heirs quiet for so long. The author of “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” “James and the Giant Peach,” “Matilda” and other classics trafficked in all the usual deadly slanders about Jews, including their nefarious financial power and their control of the media. In 1983, Dahl told the New Statesman, “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity. Maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews. I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere. Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

There was, alas, no late change of heart. In 1990, the year he died, Dahl gave another interview in which he said, “We all know about Jews and the rest of it.” To clear up any ambiguity, he added, “I’m certainly anti-Israeli, and I’ve become anti-Semitic.”

Remarkably, the obituaries for Dahl in the New York Times and The Washington Post made no mention of these grotesque public statements. And Hollywood has done its best to preserve that lucrative omission. In 2016, Steven Spielberg, who directed an adaptation of “The BFG,” said, “I wasn’t aware of any of Roald Dahl’s personal stories.” Two years ago, Netflix reportedly paid $1 billion for the rights to create an animated series based on Dahl’s works. Not bad for a Hitler apologist.

Dahl’s defenders will claim that’s entirely unfair. The man was a genius, after all, one of the greatest children’s writers of the 20th century. Allowing a few anti-Semitic remarks to overshadow his novels would only deny readers the immense pleasure of his stories. Indeed, I read Dahl’s books to my daughters when they were little, and I would still recommend them to parents and children today, but I wish we could move beyond this moment of hollow contrition.

Things were easier in the middle of the 20th century, when the so-called New Critics held sway. They insisted that only what’s on the page should be considered. All external issues, such as an author’s actions and other statements, were largely irrelevant.

But such convenient demarcations now feel wholly artificial, an intellectual version of “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?” We live in an era torn asunder by disagreements about how to regard artists’ complicated lives. Symphonies struggle with Wagner’s anti-Semitism. Museums agonize over Gauguin’s abuse of the girls he painted. Prestigious literary awards named after John W. Campbell and Laura Ingalls Wilder have been renamed to avoid appearing to excuse or ignore their namesakes’ racist beliefs.

In 2018, during the height of the #MeToo movement, news broke that National Book Award winner Sherman Alexie had sexually harassed several women. Suddenly, there were calls to stop reading Alexie’s novels. The American Indian Library Association rescinded the Best Young Adult Book Award it had given a decade earlier to his book “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.”

J.K. Rowling — perhaps the only living writer to rival Dahl’s popularity — has inspired a sharp backlash against her and the Harry Potter novels by making transphobic remarks. It’s not hard to imagine that decades from now the billionaire scions of the Rowling Corporation will issue an anodyne statement claiming that their grandmother’s comments “stand in marked contrast to the woman we knew.”

Given the false choice between amnesia and cancel culture, we’re still coming to grips with the “revelation” that creators we love can say and do despicable things. I’m reminded of a panel discussion at a literary conference I attended years ago. An alarmed member of the audience asked Cynthia Ozick if Edith Wharton was an anti-Semite. With weary exasperation, Ozick replied, “They were all anti-Semites.”

There is something significant to be gained by investigating how racist ideologies permeated the lives and works of canonical writers, but enough with the quaint expressions of horror at each discovery. Such innocent reactions only contribute to the fantasy that racism and anti-Semitism were — and are — isolated and exceptional vices like incest or beating one’s dog.

Dahl had his chance to express regret, but he chose not to — even long after the Holocaust had demonstrated to the world where anti-Semitism leads. So what exactly does it mean to apologize for a dead person’s abhorrent views? In the case of the Dahl family, their tardy acknowledgment sounds like “Roald and the Giant Bleach.” It’s a strategy closer to money laundering than repentance. If they feel some inherited responsibility for their benefactor’s comments, they’ll need to do something besides label them “incomprehensible.”

The Roald Dahl Story Co.’s contrite but largely irrelevant statement would have been much more meaningful had it been tied to the announcement of some dramatic new commitment to anti-Semitic and anti-racist organizations around the world. As voices of intolerance once again grow more shrill and confident, such tangible efforts are needed just as much as Dahl’s delightfully wicked stories.

[ad_2]

Source link