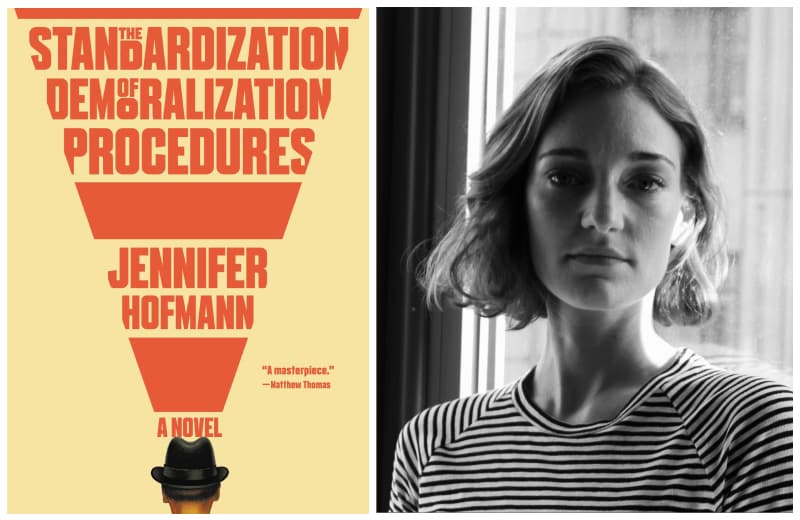

‘The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures’ by Jennifer Hofmann book review

[ad_1]

The novel opens with a nod to Gregor Samsa stirring from troubled dreams and finding himself transformed: “Something must have happened,” Hofmann writes. “Bernd Zeiger had snored himself awake and did not know where he was.” The surreal story that unfolds over one historic day suggests that he may still not be fully awake.

Zeiger is an experienced agent for the Stasi, an organization infamous for its creative cruelty in East Berlin. Early in his career, he composed a foundational text for the secret police, a guide to psychological torment called “Manual for Demoralization and Disintegration Procedures.” His one and only accomplishment in life, it’s a “work of pure genius,” a vast collection of subtle techniques such as planting “forged photographs depicting the subject in a questionable embrace with children, a neighbor’s wife, or a pet, strategically propped on a boss’s desk. Same-sex personal ads placed in the papers under the subject’s name. Unsolicited bulk deliveries of ornamental fish tanks to their homes. Pants stolen from closets and replaced with pants whose waistbands were two sizes too small.” Individually, these techniques are little more than mean gags, but as relentlessly practiced by “the most comprehensive surveillance state in the history of the world,” they effectively destroy people’s lives.

Now 60 years old and convinced he’s dying, Zeiger can sense something is amiss. “Hysteria,” he notices, “was trickling down the ranks.” A number of high-ranking officials have been suffering acute psychotic breakdowns. “Comrades known for pragmatism and levelheadedness had been spotted wandering the streets in nothing but nightgowns, screaming for Socrates at the top of their lungs.” Although Zeiger may be losing his mind, too, he’s right about the regime. The time is November 1989. He doesn’t know what’s coming, but we do: The Berlin Wall and the apparatus of oppression are about to collapse.

Hofmann, who lives in Berlin, writes with a wit so dry that it allows her to retain complete deniability. She has constructed this story as a quest, but the path forward feels like descending stairs in an Escher drawing. The systematic brutality of the Stasi is bolstered by quasi-scientific studies involving mind-reading and other paranormal abilities — research that would sound silly if it weren’t being pursued by the agency with such deadly resolve. (America wasn’t the only country with “men who stare at goats.”)

Early in the novel, Zeiger’s supervisor asks him to help track down his son, one of many young people who has “just vanished.” But Zeiger is already trying to find a waitress who vanished four weeks ago after he declared his affections. Disappearances — either escapes into the West or state-sponsored assassinations — are not so peculiar in this city. But the strange new rash of vanishings draws Zeiger’s mind back decades earlier to a physicist who was suspected of mastering teleportation. At the time, Zeiger imagined that he had kept his hands clean, but he played a crucial role in entrapping the physicist, and he watched with amazement as the man retained his secrets — and his sunny disposition — no matter how savagely he was tortured.

Now, as Zeiger seeks to unravel these nested mysteries, it becomes more clear that he’s being driven by a moral imperative, a long-repressed need to understand his responsibility for the madness he helped create and maintain. Raised through war and crushing deprivation, he has lived a life of total aloneness and blandness — the only guarantee of avoiding betrayal or extortion in this “cutting-edge, brainwashing authoritarian super-machine.” It’s not easy to make such a bureaucratic monster sympathetic, but by plumbing Zeiger’s existential crisis, Hofmann manages to reach his essential humanity.

You’ll get no plot spoilers from me, largely because I wasn’t always sure what was happening, but that, I suspect, is entirely the point. Don’t imagine that you’re just a passive observer of the events in this novel. A whole chapter in Zeigler’s psychological manual is dedicated to “inexplicableness and a lack of resolution.” Like Marisha Pessl and Rivka Galchen, Hofmann knows how to create intricate illusions of certainty in the midst of derangement. The result is a rare novel that encourages you to read as though your sanity depends on it — just a little further, just a little faster. It’s an unsettling simulation of living in a state that denies basic facts and perpetuates the most inane claims. Three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, one wishes this mind-set didn’t feel quite so familiar.

The Standardization of Demoralization Procedures

Little, Brown. 261 pp. $27

[ad_2]

Source link