They’re Taking Jigsaw Puzzles to Infinity and Beyond

[ad_1]

PALENVILLE, N.Y. — On a meandering mushroom hunt at North-South Lake in the Catskill Mountains of New York, Jessica Rosenkrantz spotted a favorite mushroom: the hexagonal-pored polypore. Ms. Rosenkrantz is partial to life-forms that are different from humans (and from mammals generally), although two of her favorite humans joined on the hike: her husband Jesse Louis-Rosenberg and their toddler, Xyla, who set the pace. Ms. Rosenkrantz loves fungi, lichens and coral because, she said, “they’re pretty strange, compared to us.” From the top, the hexagonal polypore looks like any boring brown mushroom (albeit sometimes with an orange glow), but flip it over and there’s a perfect array of six-sided polygons tessellating the underside of the cap.

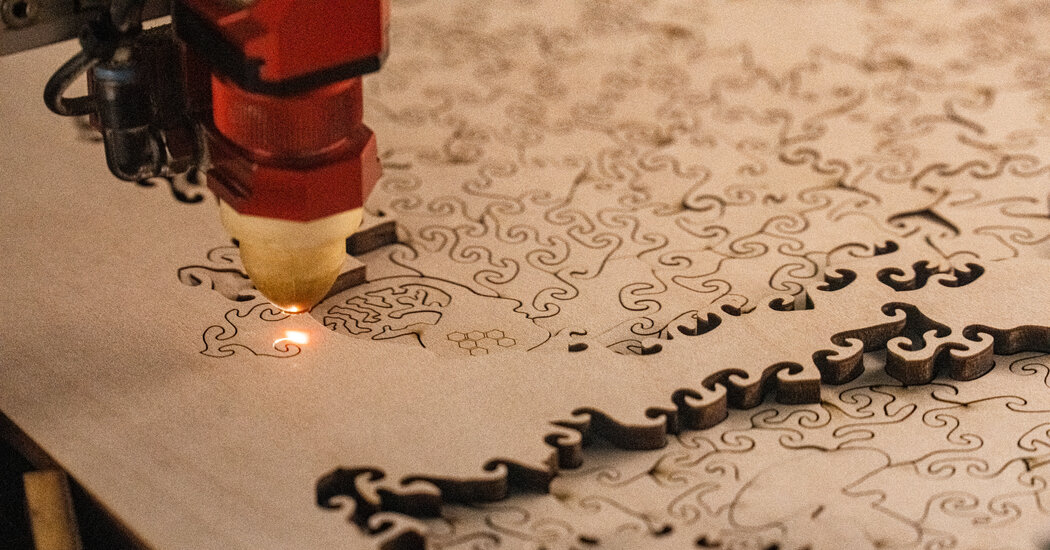

Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg are algorithmic artists who make laser-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles — among other curios — at their design studio, Nervous System, in Palenville, N.Y. Inspired by how shapes and forms emerge in nature, they write custom software to “grow” intertwining puzzle pieces. Their signature puzzle cuts have names like dendrite, amoeba, maze and wave.

Beyond the natural and algorithmic realms, the couple draw their creativity from many points around the compass: science, math, art and fuzzy zones between. Chris Yates, an artist who makes hand-cut wooden jigsaw puzzles (and a collaborator), described their puzzle-making as “not just pushing the envelope — they’re ripping it apart and starting fresh.”

The day of the hike, Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg’s newest puzzle emerged hot from the laser cutter. This creation combined the centuries-old craft of paper marbling with a tried-and-true Nervous System invention: the infinity puzzle. Having no fixed shape and no set boundary, an infinity puzzle can be assembled and reassembled in numerous ways, seemingly ad infinitum.

Nervous System debuted this conceptual design with the “Infinite Galaxy Puzzle,” featuring a photograph of the Milky Way on both sides. “You can only ever see half the image at once,” Mr. Louis-Rosenberg said. “And every time you do the puzzle, theoretically you see a different part of the image.” Mathematically, he explained, the design is inspired by the “mind-boggling” topology of a Klein bottle: a “non-orientable closed surface,” with no inside, outside, up or down. “It’s all continuous,” he said. The puzzle goes on and on, wrapping around top to bottom, side to side. With a trick: The puzzle “tiles with a flip,” meaning that any piece from the right side connects to the left side, but only after the piece is flipped over.

Ms. Rosenkrantz recalled that the infinity puzzle’s debut prompted some philosophizing on social media: “‘A puzzle that never ends? What does it mean? Is it even a puzzle if it doesn’t end?’” There were also questions about its masterminds’s motivations. “What evil, mad, maniacal people would ever create such a dastardly puzzle that you can never finish?” she said.

A ‘convoluted’ process

Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She earned two degrees, biology and architecture; he dropped out after three years of mathematics. They call their creative process “convoluted” — they get captivated with the seed of an idea, and then hunt around for its telos.

Almost a decade ago, they began researching paper marbling: Drops of ink — swirled, warped, stretched in water and then transferred onto paper — capture patterns akin to those found in rock that has transformed into marble. “It’s like an art form that’s also a science experiment,” Ms. Rosenkrantz said.

In 2021, the Nervous System duo struck up a collaboration with Amanda Ghassaei, an artist and engineer who had built an interactive physics-based paper marbling simulator powered by fluid dynamics and mathematics. (She has refined her approach over time.) Ms. Ghassaei created the turbulent flows of psychedelic color that plunge across the wavy puzzle pieces. Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg created the wave cut specifically for the Marbling Infinity Puzzle, which comes in different sizes and colors.

“There’s so many more things to explore when you’re not constrained by the physical realities of working with a tray of water,” Ms. Ghassaei said. Riffing on classic marbling patterns such as bouquet and bird-wing, the simulator allowed for more free-form results: She could combine the Japanese style of blowing ink around, using breath or a fan, with the European style of pushing ink in different directions using combs. And she could change the physical properties of the system to make the most of each technique: with combing, the fluid needs to be more viscous; blowing requires lower viscosity and faster flow.

There was a fine line, however, between psychedelic finery and “letting the color stretch and warp too far,” Ms. Ghassaei said. “That’s where the undo button was very handy.”

Cultivating algorithms

Trial and error is the Nervous System methodology. Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg started out in 2007 making jewelry (one current line uses their Floraform design system), followed by 3D-printed sculpture (Growing Objects), and a Kinematics Dress that resides in MoMA’s collection. The journal Science featured their 3D-printed organ research with Jordan Miller, a bioengineer at Rice University. They also make software for New Balance — deployed for data-driven midsoles and other aspects of sneaker stylization. The same code was repurposed, in a collaboration with the fashion designer Asher Levine, to make a dragonfly-wing-inspired bodysuit for the musician Grimes.

The route from one project to the next is marked with mathematical concepts like Laplacian growth, Voronoi structures and the Turing pattern. These concepts, which loosely speaking govern how shapes and forms emerge and evolve in nature, “cultivate the algorithms,” Ms. Rosenkrantz has written. The same algorithms can be applied to very different media, from the twisty maze pieces to the intricate components of 3D-printed organs. And the algorithms solve practical manufacturing problems as well.

A project that came to fruition this year, the Puzzle Cell Lamp, built upon research about how to cut curved surfaces so the puzzle pieces can be efficiently flattened, making fabrication and shipping easier.

“When you try to build a curved object out of flat material, there’s always a fundamental tension,” said Keenan Crane, a geometer and professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University. “The more cuts you make, the easier it is to flatten but the harder it is to assemble.” Dr. Crane and Nicholas Sharp, a senior research scientist at NVIDIA, a 3-D technology company, crafted an algorithm that tries to find an optimal solution to this problem.

Using this algorithm, Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg delineated 18 flat puzzle pieces that are shipped in what looks like a large pizza box. “By snapping the sinuous shapes together,” the Nervous System blog explains, “you will create a spherical lamp shade.”

From Dr. Crane’s perspective, Nervous System’s work adopts a philosophy similar to that of great artists like da Vinci and Dalí: an appreciation of scientific thinking as “something that should be integrated with art, rather than an opposing category of thought.” (He noted that Dalí described himself as a fish swimming between “the cold water of art and the warm water of science.”) Ms. Rosenkrantz and Mr. Louis-Rosenberg have dedicated their careers to finding deep connections between the worlds of creativity and the worlds of mathematics and science.

“It’s something that people imagine happens more than it really does,” Dr. Crane said. “The reality is it takes somebody who’s willing to do the very, very grungy work of translation between worlds.”

Recreating Earth

The Puzzle Cell Lamp takes its name from the interlocking puzzle cells found in many leaves, but this lamp is not a puzzle proper — it comes with instructions. Then again, one could ignore the instructions and organically devise an assembly strategy.

In Mr. Louis-Rosenberg’s opinion, that’s what makes a good puzzle. “You want the puzzle to be an experience of strategizing — recognizing certain patterns, and then turning that into a methodology for solving the puzzle,” he said. The psychedelic swirls of the marbling infinity puzzles might seem daunting, he added, but there are zones of color that lead the way, one piece to the next.

Nervous System’s most challenging infinity puzzle is a map of Earth. It has the topology of a sphere, but it’s a sphere unfolded flat by an icosahedral map projection, preserving geographic area (in contrast to some map projections that distort area) and giving the planet’s every inch equal billing.

“I’ve gotten some complaints from serious puzzlers about how hard it is,” Ms. Rosenkrantz said. The puzzle pieces have more complex behavior; rather than tiling with a flip, they rotate 60 degrees and “zip the seams of the map,” she explained. Ms. Rosenkrantz finds the infinity factor particularly meaningful in this context. “You can create your own map of Earth,” she said, “centering it on what you’re interested in — making all the oceans continuous, or making South Africa the center, or whatever it is that you want to see in a privileged position.” In other words, she advised on the blog, “Start anywhere and see where your journey takes you.”